In 2009 Nathan Millward spent nine months riding a Honda CT110 all the way from Sydney, Australia to London, England. This ridiculous adventure is documented in book form, and Nathan now runs guided tours of North Devon from his new base at Dorothy’s Speed Shop in Ifracombe, named after the diminutive little Honda that carried him all the way home from Australia. Nathan’s “A2 Adventure Test Days” present a unique opportunity to test seven different motorcycles from his collection while exploring the rugged beauty and muddy lanes of Exmoor national park.

After a good night’s sleep we were introduced to Nathan and his menagerie. The day would be largely road-based, as most UK green-laning adventures usually are, but a couple of muddy and rutted lanes would be laid on to allow us to test the bikes in more slippery circumstances. This was ideal, as here in the UK a bike that can’t handle a bit of greasy, wet tarmac in between the muddy bits simply won’t work for most people.

First up was something rather interesting: Honda’s not-officially-available-in-the-UK CT125, the successor to Nathan’s own legendary CT110. Essentially a reworked version of the relatively new Honda Cub 125, it was launched to great acclaim and rapturous reception in both Asia and North America last year. Exceptionally light-weight with an engaging semi-automatic four-speed gearbox, massive luggage rack and even a snorkel for river crossings, the CT seemed absolutely perfect as a low-speed trail crawler. With both feet flat on the ground, the complete opposite of the traditional sky-high seat height of most off-road motorcycles, the little Malaysian grey-import Honda was sure to inspire great confidence in slippery conditions.

Also joining us from the Japanese manufacturer were a pair of their best-selling enduro motorcycles, so-classed because of their balance between off-road function and on-road capability. The Honda CRF250 Rally and CRF300 Rally both gain a little weight compared to their stripped-down ‘L’ variants, but also feature larger fuel tanks, wider seats and a useful front fairing and windshield to make longer trips in inclement weather more palatable. The newer 300cc version supplanted its less powerful predecessor just a year ago, gaining even more fuel capacity while somehow weighing a useful 4 kilograms less.

The reason the 250 Rally was of interest to most of our party was because Nathan had fitted his example with lowered suspension, theoretically making it a less intimidating machine to approach for those of shorter stature.

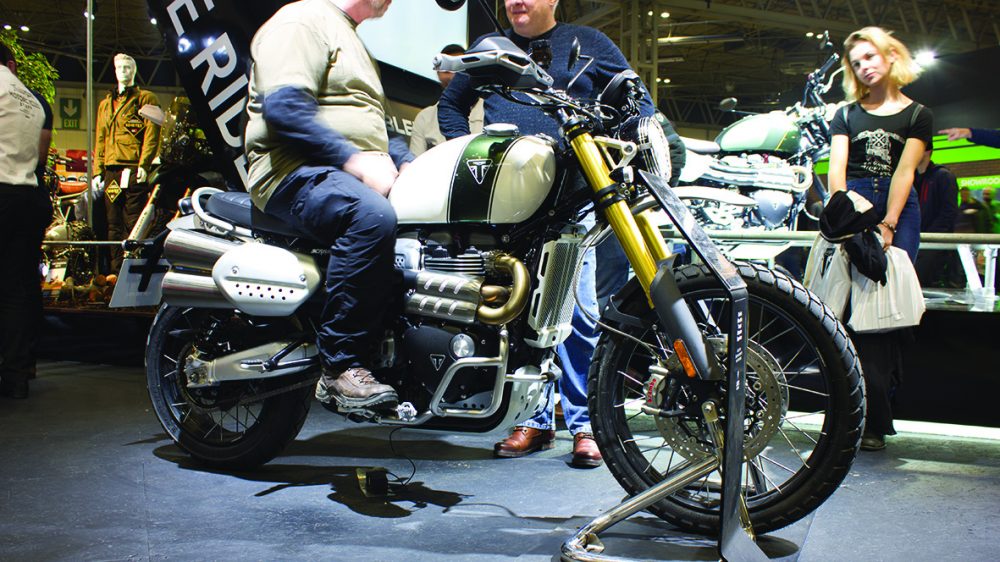

KTM joined the A2 adventure party a couple of years ago by wrapping its 390cc Duke/RC engine in a slightly more adventure-y chassis and bodywork. That said, the classically off-road focused Austrians have inexplicably opted for road-based wheels, tyres and suspension to a bike that weighed far more than any serious off-roader would ever tolerate (around 172kg at the kerb). It was clearly a fashion-first machine, rather than a serious all-road contender in the vein of its larger 790/890 Adventure lines.

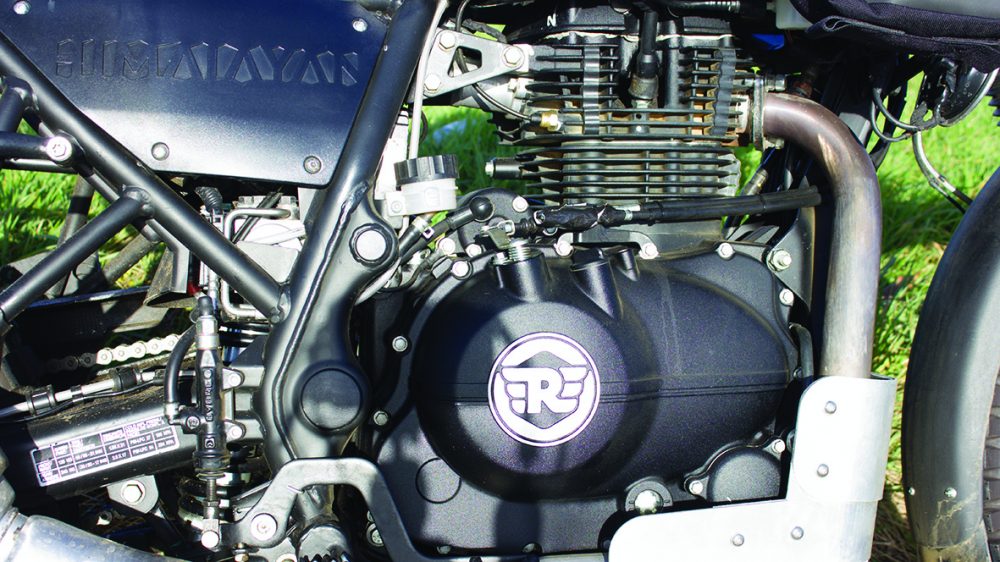

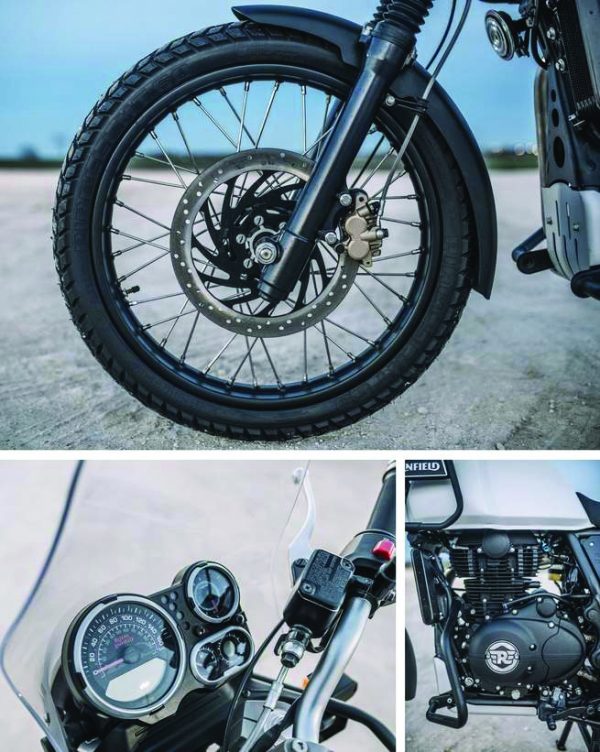

Worlds away in design terms, but manufactured in the same country as the Indian-made KTM was my old nemesis, the Royal Enfield Himalayan. I reviewed this bike when it first launched to much fanfare and enthusiasm from the world’s motorcycling press. The promise was strong: low-tech mechanicals and minimal gadgets paired with off-road-spec wheels and tyres. The reasonable 15 litre fuel-tank even sported a set of front-mounted pannier rails capable of carrying additional luggage in addition to the rear racks, all of which should have made for a genuine do-anything and go-anywhere bike.

Instead, both bikes featured in my review suffered serious mechanical failures and I was unable to look upon the model favourably. It would be interesting to see if Nathan could change my mind.

An interesting addition was another Honda: the commuter-spec CB500X. The 500cc parallel-twin was the only multi-cylinder engine in the group and was also by far the heaviest. But here Honda’s modest intent had been subverted by an expensive Rally Raid kit, replacing the cast wheels and basic suspension with entirely new hardware designed for serious off-road work. Despite this, weight would be the enemy here, the chunky CB500X tipping the scales at a portly 195kg.

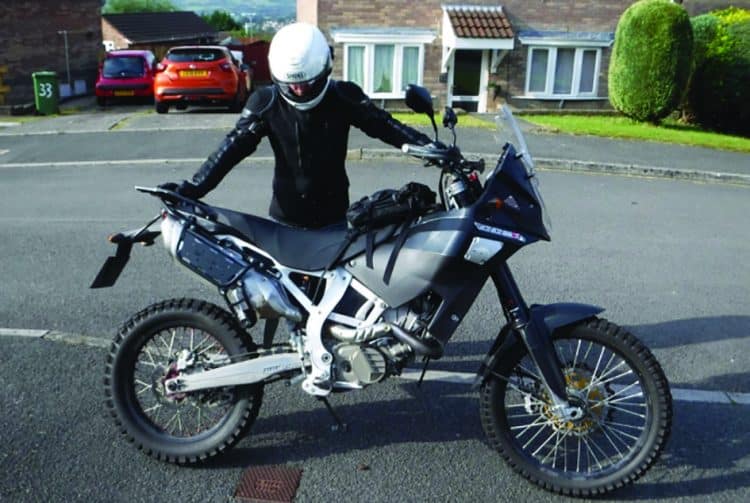

Rounding out our selection was our host’s own CCM GP450, a 450cc single-cylinder adventure bike made by the UK-based Clews Competition Machines. Discontinued a few years ago when the supply of Rotax/BMW engines dried up, my brother still treasures his, its combination of truly light weight and 20-litre fuel capacity making it an astonishingly-capable on- and off-road machine. It’s a bike with no real equal on the market today.

Our full-day ride was less than 80 miles, but it felt like far more. Everyone had ample opportunity to sample every bike as often as they liked, with stops every 20 minutes to allow for us all to swap thoughts and keys. My personal predilection for small-engined motorcycles meant that I immediately gravitated towards the semi-automatic CT125 and spent the majority of my first stint learning how to rev-match my gear changes on the widely-spaced four-speed ‘box. Despite its small size it featured a wide, comfortable seat and well-placed handlebars. The throttle was smooth, take-up from the automatic clutch was faultless, and once I’d got used to the sketchy-feeling knobbly tyres, it was an awful lot of fun.

At the end of the day, it was the bike that two of us voted as our favourite, with its utterly charming aesthetic and genuinely entertaining ride, but alas Honda UK has confirmed that it has no plans to officially offer the bike in the UK. Both myself and my friend agreed that you could probably have almost as much fun on an MSX125 as, despite the aesthetic, the CT is very much a road bike. It became very wayward in mud especially, and deep ruts and potholes quickly exhausted the limited suspension travel and ground clearance. The four-speed gearbox and low-powered air-cooled engine meant that none of us managed to break 55mph at any point during the day, and the soft suspension and twitchy handling meant that it felt very unstable at those speeds. Getting one imported isn’t difficult, but at time of writing imported versions were a difficult-to-swallow £4,500.

Two bikes none of us rated highly as genuine trail bike propositions were the KTM 390 Adventure and the Honda CB500X. Both are much larger, heavier bikes with 19″ rather than 21″ front wheels, and both engines are clearly designed for road rather than dirt. The Honda sounds great with its 270-degree firing interval and honestly felt a lot like a less powerful V-Strom 650 to ride. The Rally Raid suspension was fantastic on tarmac, doing an excellent job of providing both feel and control, and the riding position works relatively well for both seating and standing positions, helped by the chunky off-road foot pegs.

The KTM sings at revs and carves bends confidently on its road-biased tyres, though the cheap ByBre brakes are wooden and lack feel. The engine shudders and bucks if you let the revs drop, no doubt a side-effect of the aggressive tuning necessary to get a full 47bhp out of just 390cc of displacement. The KTM also suffered an intermittent electric fault throughout the day, occasionally leaving the hazard lights stuck on for no discernible reason.

The CCM GP450 divided opinion. The more experienced off-road riders thought it was great, though hot-starting issues and a flickering rear tail-light meant that even Nathan admitted it wasn’t a bike he’d want to take too far from home. I found it genuinely frightening off-road, its aggressive steering geometry making it handle much more like a road bike both on and off the tarmac. This might be a necessity with a full 50bhp and genuine 80mph capability, but also meant that the front wheel was far more willing to follow ruts and be knocked aside by stones than some of the other bikes. It wasn’t the most welcoming machine for a relative off-road novice.

Receiving both universal derision and acclaim were the Honda CRF250/300 Rally twins. The critical factor was the lowered suspension on the 250, which wallowed and swayed on the road, sitting low like a cruiser. Off-road performance wasn’t affected as much, but it made for an uncomfortable on-road experience. The 300 however, was voted the bike that the group would be most likely to actually buy with their own money.

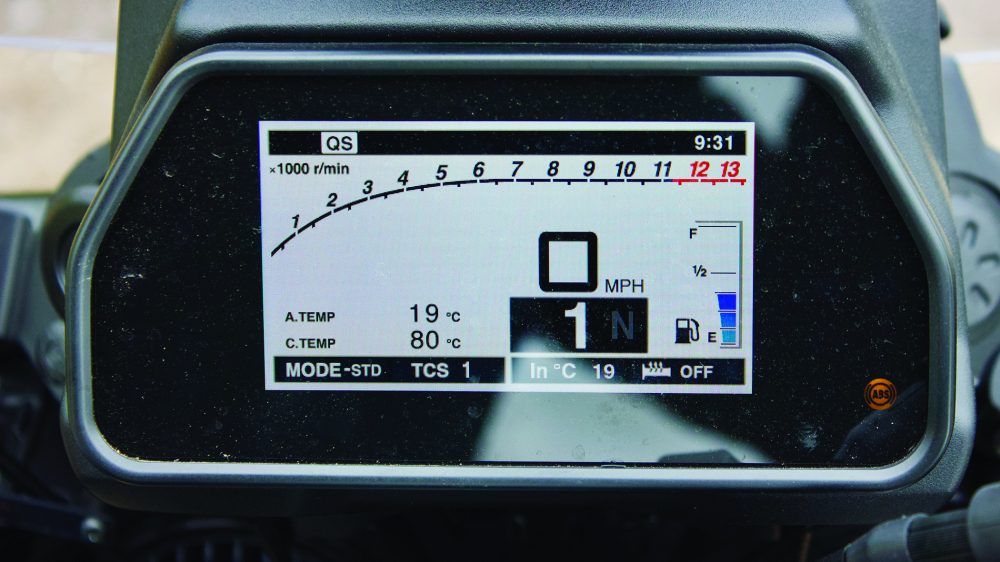

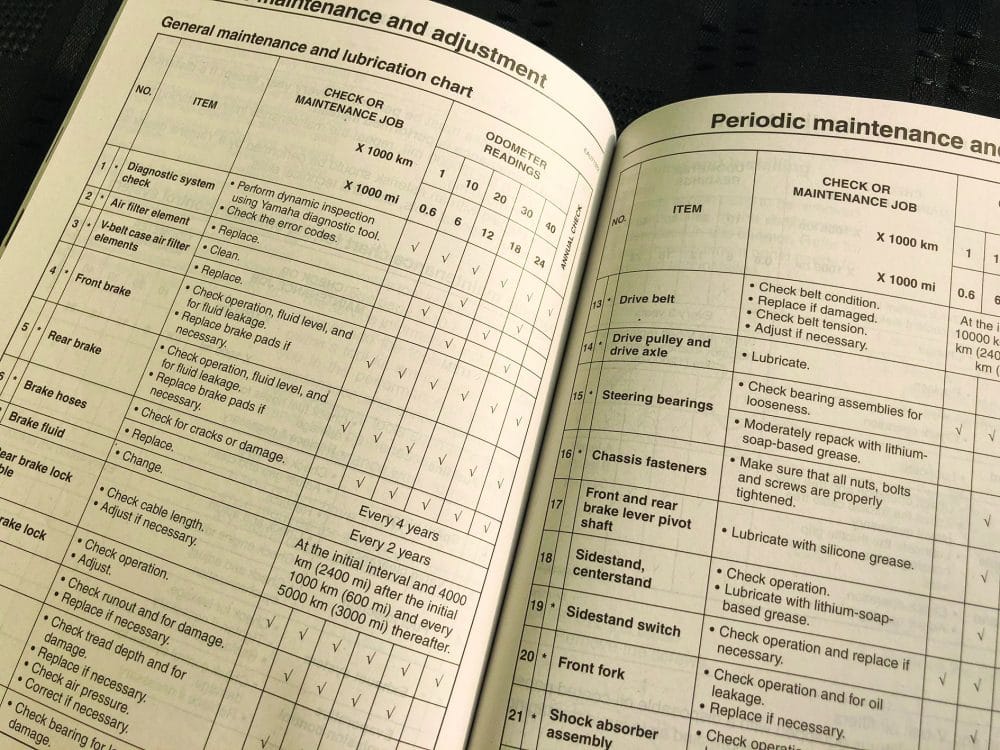

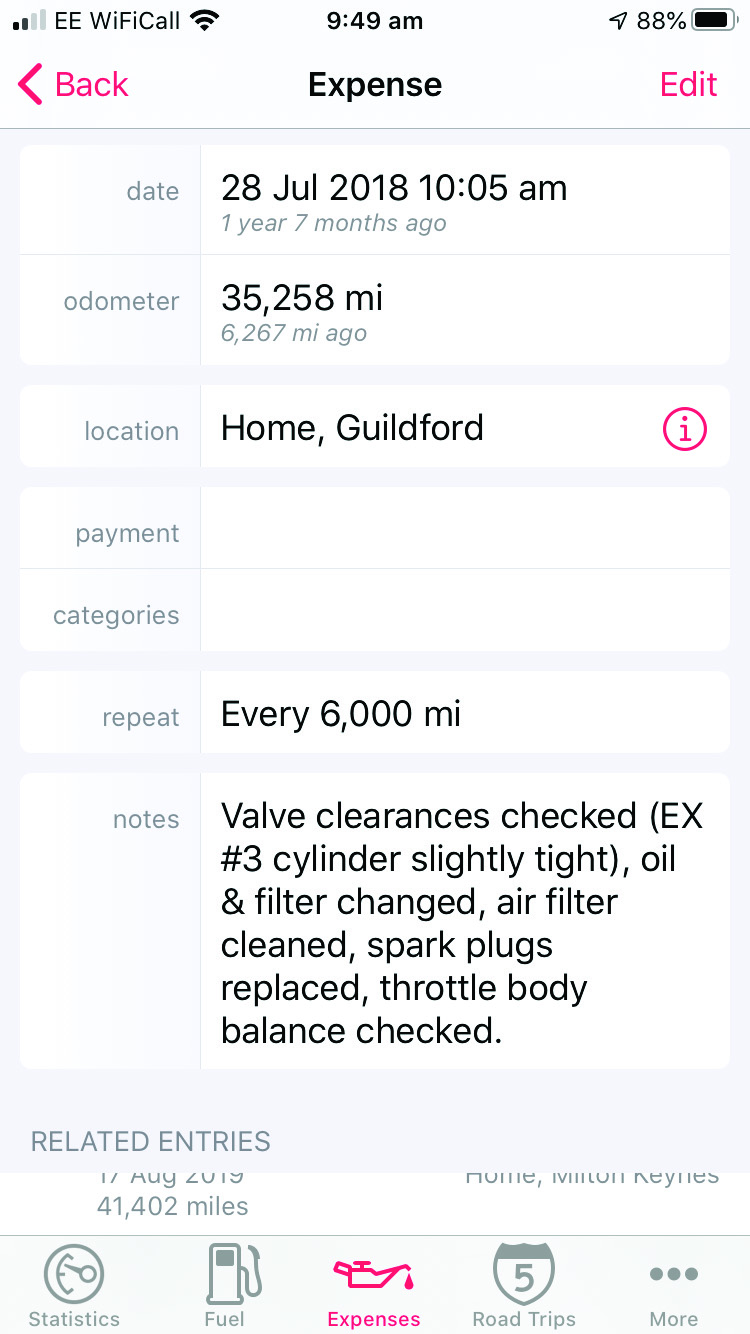

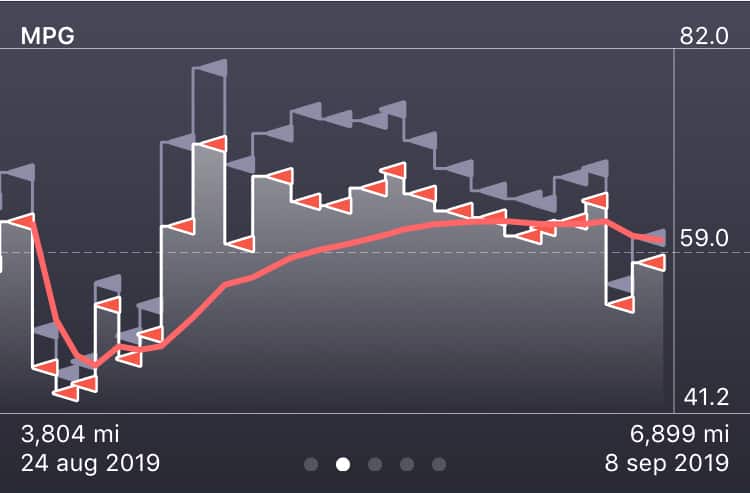

It made the off-road sections easy while handling as well as any knobbly-tyre-equipped motorcycle can on wet, leaf-strewn tarmac. The updated dashboard is great, and boasted a believable 100mpg average fuel consumption throughout the day. The ultra-soft suspension meant that the bike compressed down to a comfortable seat height as soon as it was tipped off the sidestand, and the switchable ABS system provided everyone with the confidence to make the most of the surprisingly-powerful front brakes. 8,000-mile service intervals mean that long-distance adventures don’t need to be interrupted by oil changes, never mind top-end rebuilds. It’s all very, very Honda.

But honestly, that wasn’t much of a surprise. The wildcard, and the one that surprised us all the most, was the slightly rough-and-ready Royal Enfield Himalayan. The digital components of the dashboard were unreadable due to condensation behind the glass and the front brake is so bad that many of the group genuinely thought it was broken.

India has a very humid climate, so I really can’t understand how the condensation issue hasn’t been spotted and resolved. And the brakes make absolutely no sense. The rear braking system, lower-spec on paper, somehow has bite and power aplenty. I can only assume that either a different pad material (wood? Hard plastic?) has been used on the front, or that the front master cylinder is completely the wrong ratio.

As before, a close look at the welds and materials confirms that this is a cheap bike in every sense of the word, but not cheap enough when a CRF300L isn’t that much more expensive. The Royal Enfield also much heavier, the steel frame low-tech components adding up quickly, and just half the power of the similarly-sized KTM engine. That being said, it plugs along just fine, the gear change is smooth and the clutch light. It handles more like a road bike than the CRF300 does, and in a startling turn of events was actually superior on the muddy green lanes we tested it on. Some quirk of the geometry meant that it refused to be led by ruts or rocks, staying on-course and following the rider’s inputs doggedly no matter what.

The rear wheel never tried to come around on the mud, and while deeper potholes and bumps are best avoided due to the relatively meagre ground clearance this also means that paddling over rougher terrain will be eminently doable. Nathan has ridden one all the way across the USA with nothing but a steering head bearing failure (apparently another very common fault) and was happy to vouch for its touring performance provided you stay off the faster highways.

Let me be clear: I could never buy a Himalayan brand new; the build quality and obvious design flaws would be unforgivable to me, regardless of the price. But as a used proposition? Now that’s another story. Were I to find a two-year-old example for say, half the price, the warranty having resolved the initial issues, I might be a lot more forgiving. I could fix the brakes, install some good tyres, throw on a duffel bag and hit the trails without a care in the world.

And that, honestly, is where the story should end. A fantastic time was had by all, and we all made it back home warm and dry with not so much as a snapped clutch lever. But follow the thread of light-weight adventure motorcycles far enough and you eventually catch yourself eyeing electric mountain bikes. But that’s a story for another time…

Nick Tasker

First published in Slipstream November 2021