With the global economy about to swan-dive into depths not seen for more than a century and many European governments piling on the pressure to speed up the transition to zero-tailpipe-emissions motoring, many are arguing that motorcycling faces an uncertain future. Some manufacturers are well-positioned and making positive steps to prepare for difficult times ahead, but many other old and established brands may well be caught short.

I’ve covered more miles on Suzuki motorcycles than all other brands combined, either owned or borrowed. Both of those I paid for with my own money were workhorses, used for everything from commuting to trackdays to touring, and while masters of no individual discipline they were undoubtedly competent at all of them. But miles travelled don’t translate to profits – quite the opposite, in fact, as those who actually use their bikes as practical daily transport contribute less to manufacturer’s bottom lines than our fair-weather brethren.

After 70 years, is Suzuki’s motorcycle business running out of steam?

We perhaps spend more on tyres, but dealer service schedules and pricing are directly at odds with the penny-pinching mindset of the year-round rider. And while modern motorcycles are more than capable of shouldering six-digit figures on their odometers without exploding, the market is skewed to undervalue well-used examples. PCP doesn’t work when a three-year-old bike already has 30,000-60,000 miles on the clock, and the steep depreciation hit makes regular replacement uneconomical. So we run our bikes until they literally fall apart, maintaining them ourselves to extract the best value-for-money from our investments.

The problem with building a great bike is that there’s no incentive for customers to upgrade.

The result is that brands who specialise in sunny-Sunday toys that get replaced every 18 months with well-padded profit margins have flourished in recent decades, while those making more basic but long-lasting machinery have struggled to maintain, never mind grow, their market share. I find it unlikely that the likes of BMW, Ducati, and KTM deliberately engineer their machines to fall apart after 30,000 miles; I simply suspect they don’t bother to ensure that they don’t. Their marketing departments work hard to engender customer loyalty towards their brands as a whole, not towards the particular bike that they happened to choose this PCP cycle.

Supporting that regular upgrade habit requires that there be significant perceived improvements year after year, so that a three-year-old motorcycle will seem old-hat next to the current version. While top speed, weight, and power figures were once the way to woo buyers with wandering eyes and bulging wallets, these days electronics have to provide the incentive to trade in early. But that kind of technological arms race is expensive, and those without the resources to invest in future product risk falling behind. It’s a vicious cycle – without the fancy tech to tempt owners to upgrade you don’t earn the profits necessary to fund the development of the next wave of marketable bells and whistles.

Goldwings are famous for easily swallowing hundreds of thousands of miles.

Owners love their Bergmans, but not enough bought new ones to justify further updates.

This might not be the end of the world if a given manufacturer could simply continue to sell their existing models to their core customers. But even if those customers weren’t eventually lured away by the promise of newer, better motorcycles, emissions, noise, and safety legislation mean that some degree of ongoing product development is essential. Wait too long and you’ll find you’re no longer allowed to sell some of your bikes, and your product range gets whittled away to nothing. With limited budgets, you have to pick and choose where to spend your research & development funds. And just like a battlefield medic, you sometimes have to let some of your patients die in order to save others.

This is the exact situation that Suzuki seems to find itself in at the moment. When the 2007 financial crisis hit, the Japanese manufacturers battened down the hatches, freezing research & development spending and hoping to ride out the dip. A number of European manufacturers did the opposite, using the time to develop new technology and modernise their entire product range. The result was that, as economies improved and buyers returned to showrooms, they found that there was no reason to replace their 5-year-old Japanese motorcycle – the brand-new models were exactly the same as the ones they already had in their garage. But the likes of BMW had leapt ahead, offering a truly next-generation range of motorcycles, and converting customers in their thousands. The fact that exchange rates meant that European exotica was not dissimilarly priced to more basic Japanese fare merely accelerated this shift.

Yamaha rallied magnificently with their modular 700cc twin-cylinder and 900cc three-cylinder platforms, designed from the ground-up to be fun and affordable for all. Their range was almost completely renewed in just a few years, with the resultant profits providing the necessary funds to keep bikes such as the ageing FJR1300 compliant with government legislation. Honda dragged their heels a bit, reluctant to invest in genuinely new engines and platforms, but also used their NC-series to corner the commuter/courier market at a time when no-one else was even trying to cater to those buyers. What’s more, their small-capacity motorcycles and scooters continued to sell in incredible numbers in markets that would consider a 750cc bike to be grossly oversized.

It’s also worth remembering that motorcycles are just a small part of Honda’s business, the corporation having plenty of capital to invest in long-term product planning. Kawasaki is an even starker example here, with motorcycles representing a mere footnote in a corporate portfolio that includes gigantic cargo ships and military aircraft. They’ve been able to regularly renew and refresh popular bikes such as the Versys 650 and 1000, not to mention the best-selling Ninja 1000SX, providing them with comfortable margins and a loyal customer base.

Yamaha’s bulk sellers earn enough to cover the costs of keeping the FJR alive for now.

But Suzuki has none of these safety nets, and has been struggling to attract new customers for more than a decade now. Their car business folded entirely in the United States and is facing tough competition across Europe in the low-cost segments from the likes of Hyundai and KIA. Their small-capacity bikes remain popular in south-east asia, but profit margins are thin and increased competition from the Chinese manufacturers is eating into their volume. Europe and America used to be the cash cows whose high-margin product paid the research & development bills, but those funds have been drying up for a long time now.

The result is that Suzuki’s product range has stagnated, with key lines being forced to retire due to increasingly-stringent emissions legislation. What little money remains has been spent carefully, one bike at a time, in the hopes of striking gold and kick-starting a sales success that could, in turn, fund further development of their ageing lineup. But time and time again it seems that the upgrades and face-lifts are too little, too late, and always one or two steps behind their competition.

A popular, steady seller, but the money for Euro 5 upgrades just wasn’t there.

The V-Strom 650 remains a steady, if unspectacular seller amongst the practically-minded, which is probably why Suzuki has continued to spend the minimum-necessary funds to refresh the design and stay ahead of emissions legislation. The fully redeveloped V-Strom 1000 launched in 2014 with the fanfare befitting a major brand’s new flagship, but BMW had stolen their thunder with the all-new watercooled and tech-laden R1200GS just one year earlier, and buyers weren’t interested. With PCP the new and exciting way to make expensive bikes affordable, the lacklustre residuals of historically rust-prone Suzukis made their bikes deeply uncompetitive in this strange new financial landscape. It didn’t matter to most people that the retail price was thousands of pounds cheaper; if you were buying on PCP, then BMW offered you a lot more bike for very similar money.

Pivoting towards their traditional cash-cow, the GSXR-1000, may have seemed sensible, and in 2017 we got an all-new litre-class sportsbike with modern electronics and segment-competitive horsepower figures. But this was the first serious effort in over a decade, and those traditional customers had moved on. With the Japanese brand now seen as a budget alternative to the more desirable European offerings, matching the now well-established upstarts on the spec sheet wasn’t enough to bring buyers back in sufficient droves. What’s worse, choosing to pin their hopes on these two big bikes meant that the money necessary to keep the GSX-R 600, GSX-R 750, Hayabusa, Bandit 650/1250, and even the Burgman 650 compliant with the latest round of European emissions regulations simply wasn’t there. Visit a Suzuki dealership today, and the choices are looking very limited indeed.

The 2014 V-Strom 1000 was fantastic, but customers ultimately voted with their wallets.

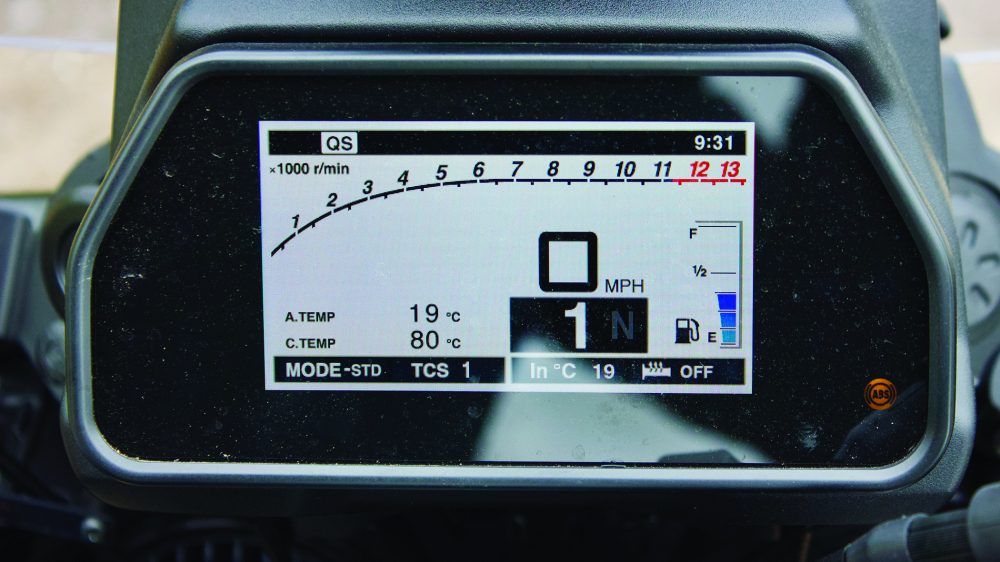

Which brings us to Suzuki’s latest refresh of their big adventure-tourer in the shape of the new(ish) V-Strom 1050. Suzuki is counting on the styling to do the lion’s share of the work, and it’s certainly succeeding in turning heads amongst the traditional motorcycle press. And if the public show the same interest, Suzuki is hoping that the technology upgrades will carry them the rest of the way to their cheque books. We’ve got cruise control, lean-sensitive ABS & traction-control, not to mention various gimmicks like hill-hold assist. We’ve also got a new LCD dashboard, just in time to be considered out-of-date next to the current crop of big-screen full-colour TFT dashboards the competition are triumphantly displaying. Still, it works, and it’s a pleasant enough bike that does a perfectly adequate job of being a good all-round motorcycle.

But while Suzuki have increased the spec to match their competition in the adventure-touring space, they’ve also upped the price to match, giving up their value card and going toe-to-toe with the likes of Triumph’s new Tiger 900 and Ducati’s Multistrada 950. And as much as I am a fan of Suzuki and their V-Strom line in particular, I don’t think this is a fight they can win. Personally, I’m not sure I trust Ducati’s engines to last 100,000 miles without serious work, and the servicing schedules and costs are clearly not designed with high-mileage riders in mind, but it’s a much more exciting bike to ride. My experiences with modern Triumphs suggest that they can shrug off salty British winters far better than a V-Strom can, but again – servicing costs become prohibitive when used regularly.

I’d like to say that this is an area where the new V-Strom has retained its edge, but dealer rates for both basic oil changes and valve adjustments are equally eye-watering. I’ve historically found that Suzuki’s motorcycles are very easy to service at home, so a competent home mechanic might perhaps choose the Japanese option for this reason alone. But as stated earlier, the people willing to spend £12,000 on a motorcycle and also get their hands dirty maintaining a 20,000-mile-per-year vehicle are a very small and unprofitable minority. Suzuki was hoping to lure in buyers from other brands, but I fear all they’ve actually done is freed up their existing customers to go elsewhere.

The new V-Strom 1050XT looks the part, but underneath it’s a 6-year-old bike. Competition is fiercer than ever, especially at this new, higher price point.

For my part, I’m planning to spend some more quality time with the top-spec V-Strom 1050XT soon. While my short initial ride failed to disappoint in the way that many over-hyped and over-priced alternatives have, it also failed to bowl me over. If my own personal V-Strom 650 exploded tomorrow and I wanted a well-specced replacement, it’s newer, bigger brother would do a fine job of filling those particular boots. But the market for sensible, upright, all-weather do-everything road bikes is now very, very crowded, especially at this price point. I’ve got an appointment to look at both Yamaha’s Tracer 900GT and have my name down for a ride on a Moto-Guzzi V85TT as soon as it’s available. Ducati’s Mulistrada 950 waits in the wings, and BMW are trying hard to tempt me with their new F900XR. And finally, there’s the Tiger 800 XRT that so impressed me last year, and its brand-new 900cc replacement.

If Suzuki can’t keep me as a customer, then who else is left?

Nick Tasker

First published in Slipstream July 2020