Are motorcycles finally ready to embrace electric motors?

2020 will be remembered for a lot of (mostly terrible) things, but it also stands to become the turning point for electric car ownership in Western Europe. A number of regulatory and social factors have collided with the relentless march of technology, and electric cars are finally good enough to replace their petrol-powered versions for many people.

There is now genuine choice from a broad swathe of manufacturers at a wide range of price points and form factors. Need something cheap and cheerful? The Renault Zoe has you covered. Got kids to haul around? The Kia E-Niro awaits. Money to burn? Sir or Madam’s Porsche Taycan is right over here. Time to replace your Volkswagen Golf? Try the ID3. All good cars at competitive price points, and despite their high-tech electric powertrains they are all genuinely usable real-world transportation.

Car manufacturers in Europe are under the gun of course, with new internal-combustion-engine (ICE) powered cars set to be banned from sale in the next couple of decades. The UK government has triggered one of the shorter countdowns, with 2035 looming large for manufacturers who have yet to dip a serious toe into electric waters. True, questions remain on how those forced to park on the street will charge their cars, and our high-speed recharging infrastructure is a patchwork of broken and incompatible chargers, but I’m confident that those problems can be solved in time. Price and range still leave room for improvement, but we’re honestly not far off. No, the bigger question and my chief concern is how our precious motorcycles will fare in this brave new world.

For now, the upcoming UK ICE ban does not include motorcycles and scooters, so it sounds like you’ll still be able to buy petrol-powered two-wheelers in 2035. Of course, there’s plenty of time for our Government to change its mind, and even if not, it’s only a matter of time before ever-tightening emissions regulations squeeze the petrol out of your tank. It’s also true that our electric two-wheeled choices are getting better, even if pickings are slim at the moment. In a few short years promising newcomers Alta Motors and Mission Motors have both risen and then fallen again, while electric pioneers Zero have been quietly, ahem, plugging away.

Despite Harley-Davidson’s £30,000 Livewire and its high-profile television debut garnering all the publicity, it’s Zero’s new SR/S that caught my eye this year. Essentially a faired version of 2019’s SR/F, the SR/S and its naked sibling mark a turning point in Zero’s product design and capabilities. Their previous offerings with their less powerful, shorter-ranged bikes never caught the imagination of mainstream motorcycling. Performance and finish quality equivalent to a 20-year-old Kawasaki Ninja 250 and asking prices not far removed from high-end Ducatis were of little interest to all but hard-core early adopters, though they did show up in some odd places. I’ve never ridden one because, quite frankly, they were just too expensive and too short-range to be serious contenders for any of my purposes.

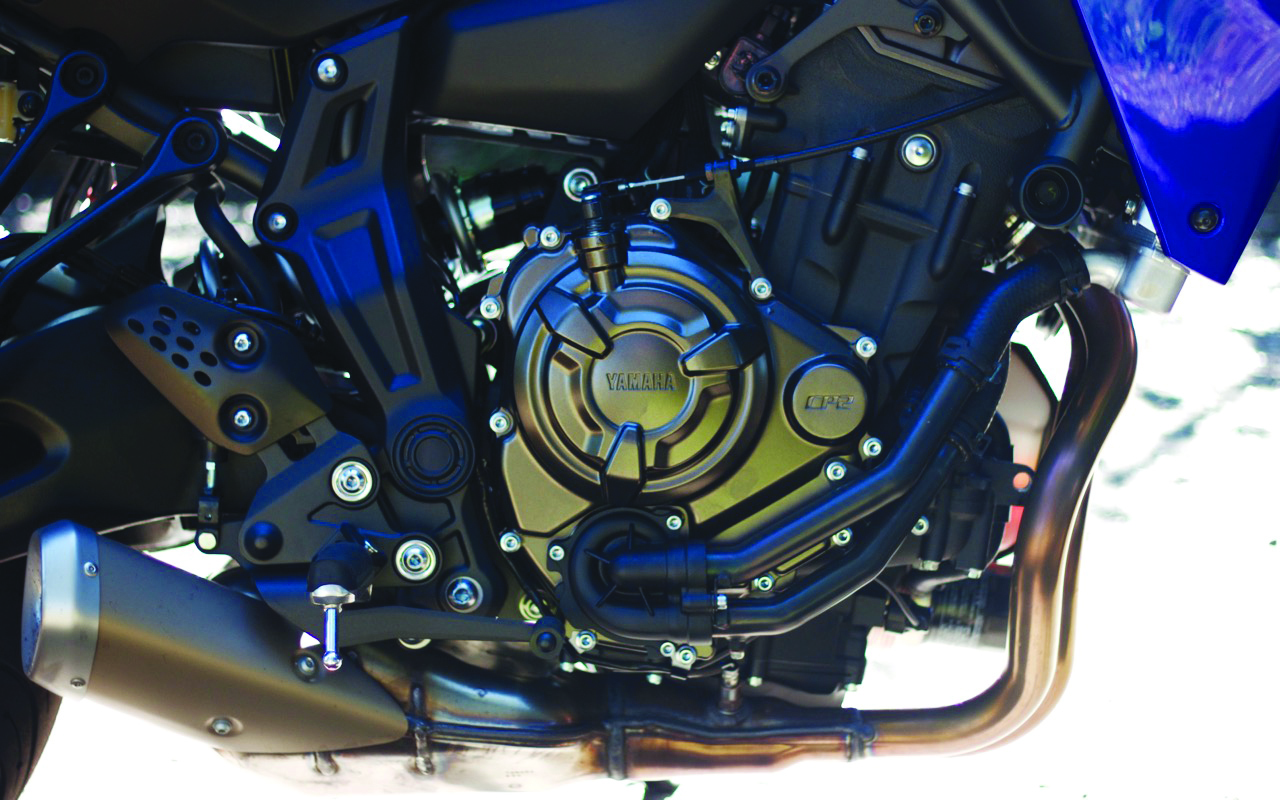

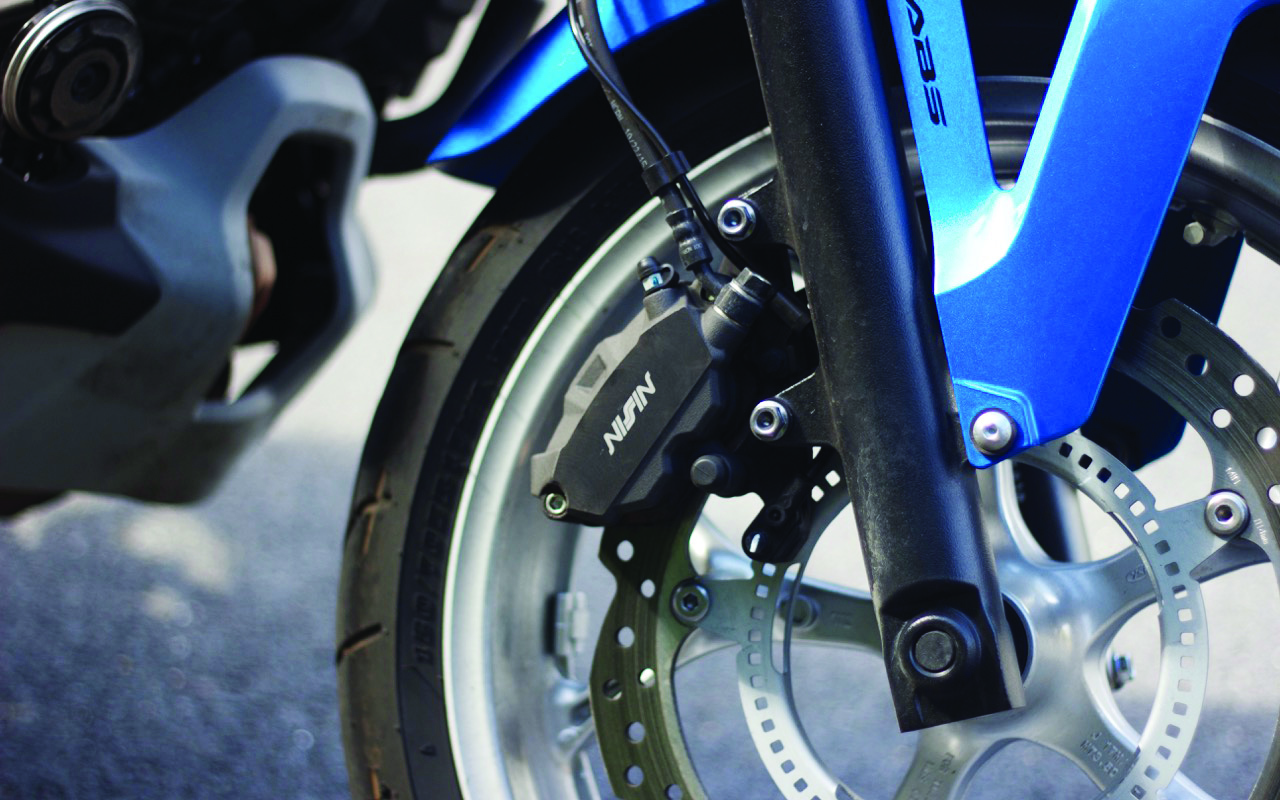

But the new SR platform is a very different beast. Gone are the spindly wheels and questionable running gear, and instead we’re looking at proper modern sports bike tackle. Sure, the J. Juan brakes are an oddity and don’t quite match the bite and power of the best Italian or Japanese competitors, but twin four-piston radial-mount calipers are nothing to sniff at. Showa adjustable suspension front and rear ticks a quality box, while LED headlamps and a TFT dashboard present the very picture of high-tech modernity. But where you’d expect to see cylinder heads and a catalyst-packed exhaust system poking out from under shiny plastics, we instead see a lightly-finned battery pack and gold-anodised electric motor.

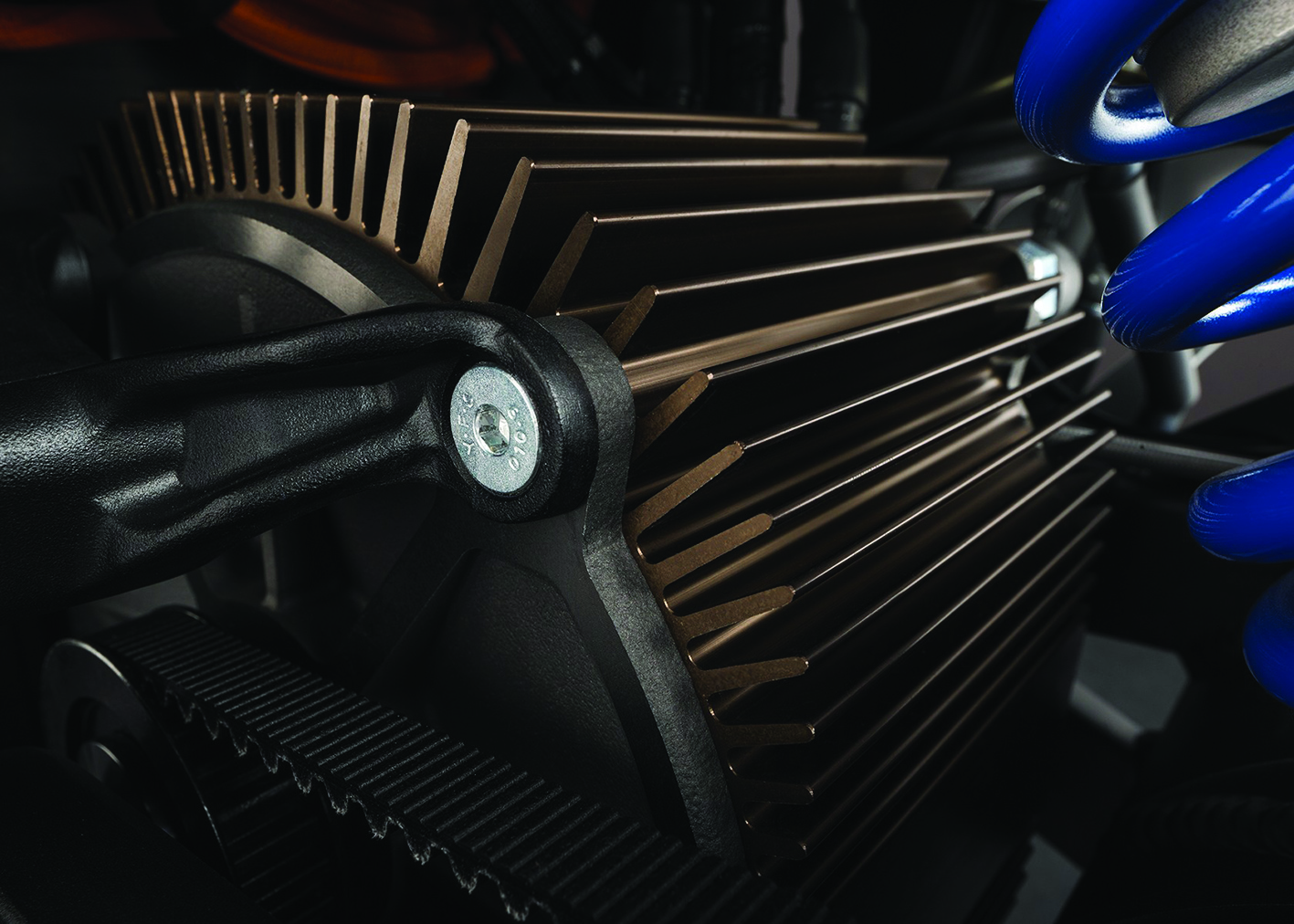

And what a motor it is. Packing 110bhp and a frankly ridiculous 190Nm from a single moving part, Zero’s latest-generation permanent-magnet brushless motor spools the fat 180-section Pirelli Diablo Rosso 3 rear tyre up through a maintenance-free kevlar belt drive. Numbers like this have to be taken with a pinch of salt, because the way that electric power is delivered is so different to what we’re used to. But in the right throttle mode, the SR/S builds speed more than quickly enough. I actually suspect that output at lower speeds is being limited by the traction control to prevent either burnouts or wheelies, and I wasn’t brave enough to try switching it off.

Conventional… until you notice the lack of exhaust

Zero were one of the first to market.

An unassuming piece, this beast of a motor has to be held back by electronics.

Even my dealer had trouble adjusting the settings, and that was with the bike stationary.

There’s a hell of a lot to like about electric powertrains. Obviously, electricity is cheaper than petrol, but the fact that you can top up at home and leave the garage with a fresh ‘tank’ every day is a novelty that never gets old – or so I’m told. At a stroke, zero-emissions zones are of no consequence, and you’ll never wake up your neighbours leaving for an early Sunday blast, nor get dirty looks from people as you rattle past them outside peaceful village cafes. The instant on-demand power at any speed is addictive, and you’ll never experience a power train with more immediate throttle-response.

The ownership experience should be more relaxing, too. All those dirty, messy, oily reciprocating parts are gone, replaced with a big sealed battery pack and a spinning shaft inside some electromagnets. There’s no oil to change, no valves to adjust, no filters to replace – not even a chain to lubricate! Aside from your tyres and brakes there’s nothing to warm up when cold, nor anything to bed in when new. An electric motor is a devilishly simple thing compared to the incredible complexity of an internal combustion engine, and needs practically no maintenance. And that’s what makes Zero’s insistence on a 4,000-mile service schedule so baffling. Yes, pivot points need lubricating and brakes and tyres need checking, but not even Suzuki insists on dealer visits that often. Still, an electric motorcycle is a prime candidate for easy low-cost home servicing.

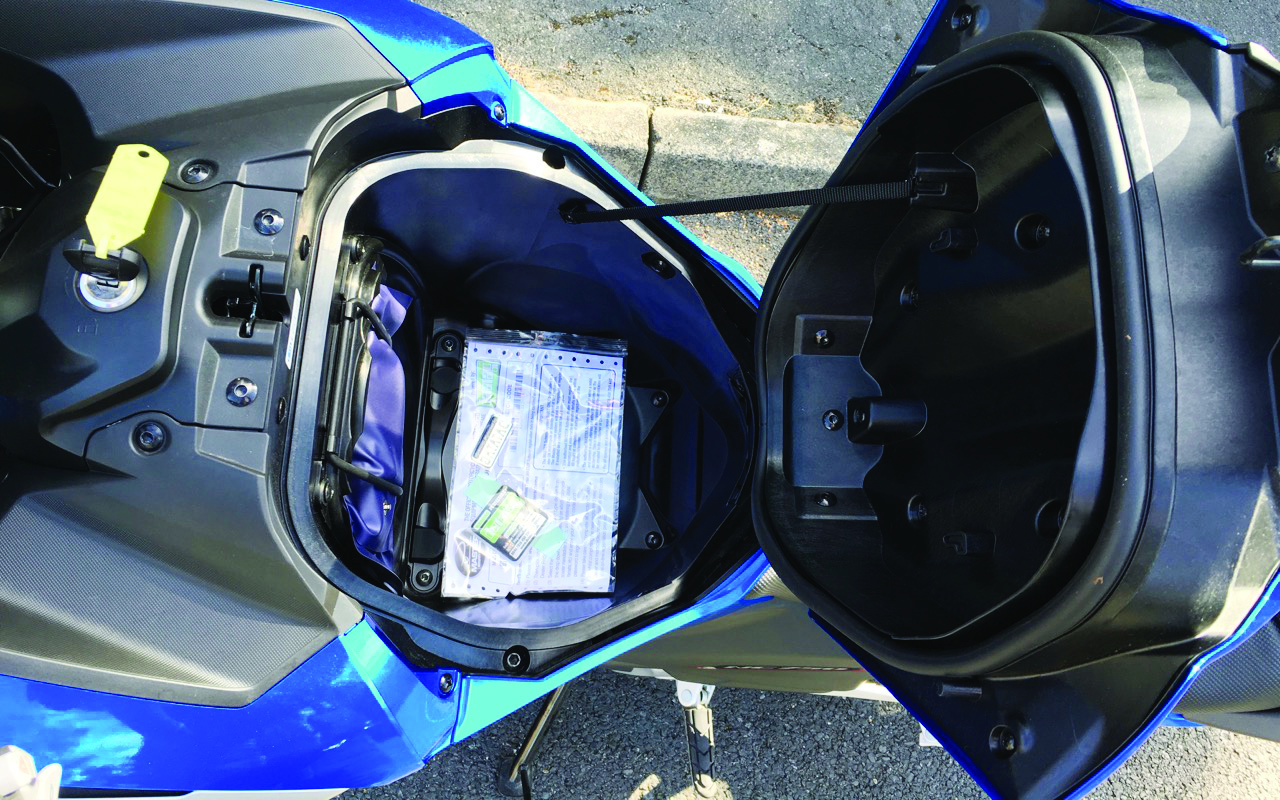

But there are downsides too – both to electric motorcycles in general and the Zero SR/S in particular. Electric motors are extremely efficient at turning energy into motion (95+% is not uncommon) with petrol engines struggling to convert more than 20-35% of their fuel into motion. Yet even state-of-the-art lithium-polymer batteries are hopelessly poor at storing energy when compared to liquid fuels. Based on a number of sources, it’s generally agreed that the energy density of a high-tech 14.4kWh battery pack like the Zero’s is handily beaten by just two litres of bargain-basement supermarket petrol. And that battery pack is heavy, pushing the otherwise mechanically simple SR/S up to a meaty 230kg curb weight.

The efficiency of that electric motor is a good thing then, because I doubt that even my V-Strom 650 would get very far on just two litres of fuel. But while Zero claim 150 miles’ range in the city, after just 13 miles of mixed riding I had already drained 23% of my battery’s charge. Ride normally and a fully-charged battery wouldn’t get you much more than 60 miles. Ride hard and you wouldn’t last an hour before stopping dead at the side of the road. Trundling in a more relaxed manner between public charging points might make a new type of touring possible, but one mistake and you’d be calling for someone to collect you in a van.

No clutch lever, obviously – just direct, instantaneous drive.

Commuting might make more sense. Regenerative braking, where ‘engine braking’ is actually the electric motor converting your unwanted momentum back into electricity, makes stop-start traffic a far less wasteful endeavour, and the average European commute would be comfortably handled by the Zero’s battery pack. My own ~70 mile round-trip to work and back might be a challenge, except that my employer has installed free electric charge points all around the parking lot. I’m the perfect target customer for a good electric motorcycle.

But while the Zero SR/S nails the electric part, it falls somewhat short on being a good motorcycle. I was actually surprised when I checked the specs later and found that the bike weighs ‘only’ 230kg, because on the go it feels like it weighs a lot more. In a straight line, even on bumpy roads the suspension does its best to hide the bulk, but arrive at a corner and suddenly you realise that there is almost no feel from the front forks. I can only surmise that the suspension and chassis are simply underdeveloped, the result of a tech company building a drivetrain first and a motorcycle second. The bike understeers when first tipped in, then dares you to lean it further to complete the turn, all while the front end is communicating nothing about how much grip is actually available. The contrast to Kawasaki’s identically-weighing Ninja 1000SX could not be starker.

Approaching a corner is almost as bad as riding around it. The brakes are fine, but again, the front forks let them down. You don’t have the confidence to squeeze hard, and for some reason the sportier the riding mode, the less of a braking effect the motors are programmed to give you. The result is that you freewheel into every corner as though in sixth gear, yet don’t have the front-end feedback you’d need to trail-brake to compensate. And before anyone suggests dragging the rear brake as a solution, it’s so ineffective that it’s barely adequate for slow-speed manoeuvres, never mind high-speed corner entry!

That battery sits low in the chassis, but doesn’t actually hold that much energy.

J.Juan front brakes are fine, but Showa-sourced forks deliver little feedback.

Unpack your sandwiches and a good book, and plug in the charger.

Direct-action shock absorbs bumps well, with plenty of adjustability.

Perhaps these handling issues are merely a symptom of my age-old problem – I simply don’t weigh as much as the suspension’s designers anticipated. Zero is an American manufacturer, so their average rider specification may well skew heavier than the European or Japanese brands. I am usually able to determine whether a suspension is otherwise good or bad just by riding it, and can make an educated guess as to how the bike would perform once adjusted for my lighter stature. But in the case of the SR/S, I simply can’t tell. Maybe the Zero would positively scythe down British B-roads after £1,000’s worth of suspension work, but that’s a heck of a gamble on an already £20,000+ motorcycle.

Switching the bike into ‘Street’ or even ‘Eco’ mode cranks up the regenerative engine braking in stages, and ‘Eco’ provides much more natural control going into bends as a result. But with the throttle set this way getting back on the power is so slow and woolly that you lose all precision, making corner exits a sloppy mess. My dealer tells me that it’s possible to configure a ‘Custom’ mode that would combine the crisp throttle-response of ‘Sport’ with the maximum engine braking I craved, so maybe that would provide a solution for more enthusiastic riding.

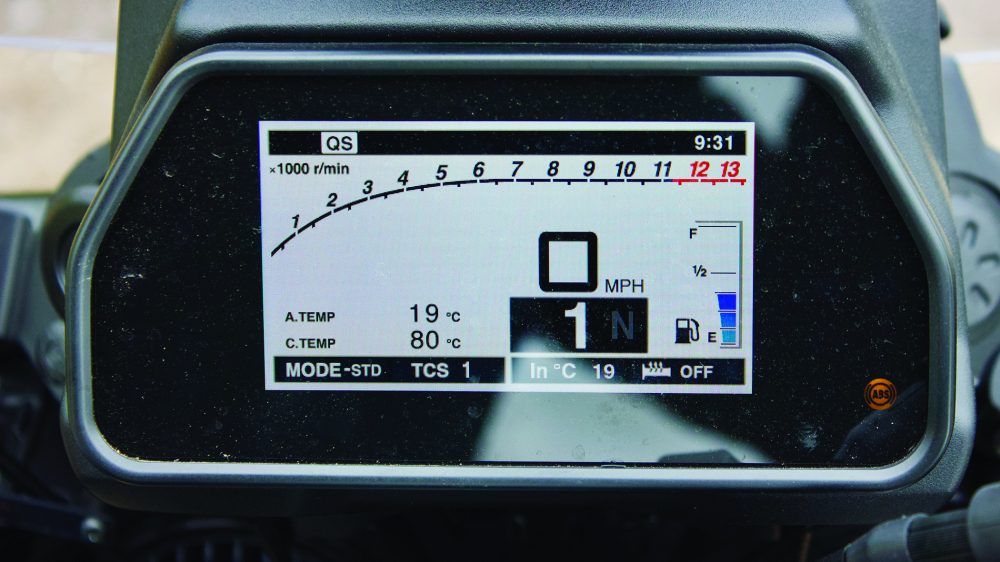

But switching back into a gentler mode for cruising is not easy. The clunky mode-switch requires multiple press-and-hold operations, and you’ll need to spend a frankly dangerous amount of time looking at the dashboard to confirm that your inputs have been registered before moving on to the next stage in the process. Imagine trying to program the timer on a digital watch while also riding a motorcycle and you’re just about there. The heated grips are a similar story – adjusting the heat requires delving into a menu and holding various mode switches down for a few seconds. Would an extra button or two really have been so hard?

And the thing is, when riding progressively an experienced motorcyclist will adjust their engine braking constantly by selecting the appropriate gear for the speed and difficulty of each corner. Binding the regenerative engine braking to throttle modes makes this impossible, and makes you wonder why there isn’t a foot-operated lever of sorts that would allow you to adjust the level of the effect in real-time? Electric cars do this exact thing with paddles behind the steering wheel, and the concept works perfectly.

The overall impression the bike gives is of a product entirely built around its core technology, with details at the periphery left as something of an afterthought. The much-lauded hard luggage requires one of the ugliest pieces of bolt-on scaffolding I’ve ever seen, and the optional top-box mount is barely integrated at all. The bike is meant to epitomise the latest in high-tech transportation, yet features what I believe are 2006 Triumph Daytona 675 filament-bulb indicators. The switchgear is rather cheap and nasty, and the plastic hatches on the faux-tank and charging ports are very flimsy indeed. When so much of the bike oozes class, these other pieces stand out a mile and would really spoil the ownership experience.

No gear lever, of course, but you do get belt-drive and a centre stand.

The seat seems fine for short trips; you’ll never get a chance to try it on long ones.

The seat and general riding position is relatively comfortable and nicely detailed, the paint and lines of the bodywork clean and uncluttered in pleasant comparison to many modern motorcycles. The wing mirrors are incredible – mounted low, like old BMW tourers, they provide a clear rear view completely devoid of shoulder or elbow. I’m a fan of the clean and easy-to-read dash, even if the user interface for configuring it is a nightmare. For my height the windshield works really well, keeping pressure off my chest but directing clean airflow at my helmet. With the handling issues resolved, it would be a lovely motorcycle to spend time on.

Low mounted mirrors are excellent, something other manufacturers should take note of.

Really well-judged screen is effective, with no adjustment necessary or possible.

Of course, that brings us back to the range, because you’d be spending just as much time drinking coffee while it charged as you would riding it. And that’s not really Zero’s fault, who have been relentless in their push to bring practical electric motorcycling to the mass market. Harley-Davidson’s LiveWire can reportedly get a little further on a full charge and has the added benefit of DC fast-charging support, rare as such chargers are in the UK. Given Harley-Davidson’s more extensive experience of actually building motorcycles, perhaps the overall result is a little more cohesive – although you’ll certainly pay for it. A brand-new LiveWire makes Harley’s petrol bikes seem cheap at an eye-watering £30,000 a piece.

Consider the specifications and performance of both these examples and you’d reasonably expect petrol-powered equivalents to cost around half what Zero and Harley-Davidson are asking for their premium electric motorcycles. And while electric cars seem to be around £5,000-10,000 more than their internal-combustion cousins on a spec-for-spec basis, it’s a fact that those massive battery packs add a tremendous cost to the parts list. The SR/S and LiveWire have batteries that are much, much smaller, so where is all that extra money going?

I fear that the answers lie in sales volume and development costs. Even if electric vehicle battery cells can be purchased wholesale from any number of suppliers these days, developing a good motor and the supporting electronics costs money. Then there’s the engineering required to slot it all into a modern chassis, whose design has been steered by the physical dimensions and necessities of internal combustion engines for more than 100 years. Styling, marketing, user interface design – all the things that don’t directly contribute towards the individual cost of a product must still be paid for in the end, and when that cost is spread over a relatively small number of customers, each sale must cover a larger chunk. Later, when all that prior expense has been paid off, and if the products continue to sell, then prices can come down. That’s why a new Suzuki SV650 today is significantly cheaper than its inflation-adjusted 1999 ancestor. Cars, even electric ones, can amortise those costs over hundreds of times as many actual sales, rapidly closing the gap on their petrol-powered versions.

The people who jump in at those early price points, who are willing to pay an outsized chunk of the manufacturer’s research & development costs are called early adopters, and it is they who Zero and Harley-Davidson and all the other nascent electric motorcycle manufacturers are aiming for. They need that money to pay for the work that’s already been done, so that future models can be offered to the rest of us at more palatable price tags. And perhaps some of that money will go towards refining the experience, sanding down the rough edges and ensuring that those future products aren’t just notable for their powertrain, but instead notable for being really great motorcycles.

TFT dash is easy to read, but the user interface is an ergonomic disaster.

That battery doesn’t cost £10,000, so why is the SR/S £10k more than a Ninja 1000SX?

Rear brake is terrible, barely enough for low-speed manoeuvres.