Feet-forward riding position? Low-speed comfort, lockable luggage and epic fuel range? Surely there can be but one solution – a mid-capacity scooter!

Scooters are much-maligned here in the UK, our past obsession with sports bikes often pointed to as the reason why we are apparently the sole nation on this continent not to whole-heartedly embrace this most practical form of two-wheeled transport. Visit a major European city and they’re absolutely everywhere, complete with massive windshields, huge top-boxes and leg-covering scooter skirts. Unfashionable? You may think so, but the Italians seem to disagree, and fashion is kind of their thing.

First impressions are good, but probably depend on your own aesthetic preferences. I happen to like the angular spaceship-with-wheels styling, but I’m sure it isn’t for everyone. The wheels are well-proportioned, although at fifteen inches are still considerably smaller than what most of us will be used to. Where the Forza begins to really impress is when you take a closer look and start to dig in to the spec sheet & features lists.

To start with you get full LED lighting from stem to stern – no incandescent bulbs to fail unexpectedly while on tour, which means no need to carry spares. They’re also a damn sight brighter, and do a great job of attracting the attention of perennially distracted car drivers. Next up, a centre stand comes included, something that – with fitting – often adds close to £400 to your average adventure-tourer’s price tag. Unfortunately, it turns out the real reason for this is that the Honda refuses to start or run while the side-stand is extended, a safety feature necessitated by the automatic twist-and-go gearbox on the Forza.

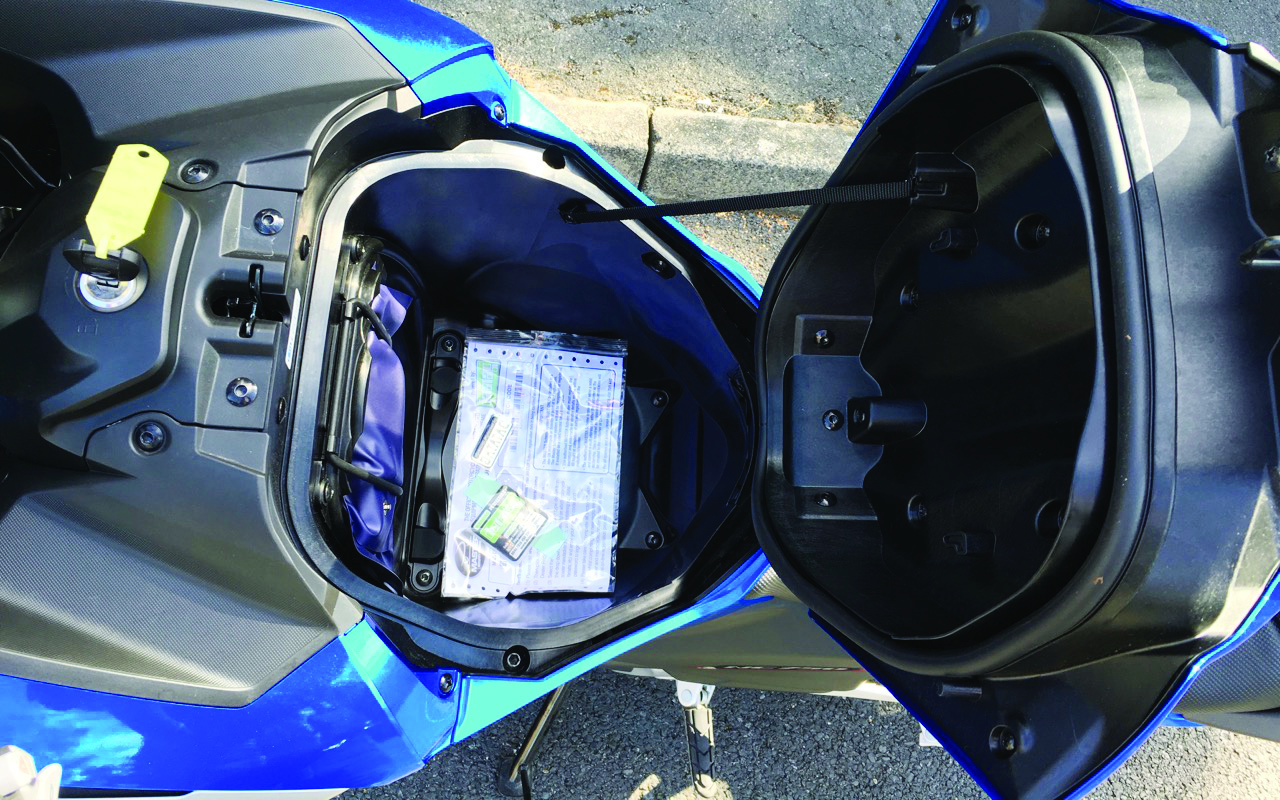

At the back we have a secure cavernous under-seat storage area, easily matching the capacity of an average top-box, while simultaneously keeping any luggage weight low to the ground. A top-box is available if yet more storage is required, with the added benefit of being linked to the same keyless access system the ignition uses.

That’s right – up front, there’s nowhere to insert a key, a proximity fob similar to many high-spec cars is provided instead. As long as this key is somewhere about your person, you can push the ignition knob to activate the system and then twist it to the relevant position. Setting the ignition to On wakes up the comprehensive dashboard tucked away inside the fairing. Road & engine speed are represented by large dials with easy-to-read numbers either side of an inverted LCD display. Here a bored rider could monitor air temperature, charging system voltage and instantaneous fuel consumption, alongside the usual twin trip meters and multi-segment fuel-gauge and coolant temperature.

Settings can be scrolled through using the left-hand switch-gear, which also includes the controls for disabling the traction control system (not really necessary with just 25bhp) and raising and lowering the electronically-adjustable screen. This last piece of equipment sounds great on paper, reacting quickly to the controls and allowing you to keep your view clear around town and dial in more wind protection on the motorway.

It’s very telling that we’re almost 1,000 words into this review and I have yet to mention the brakes, suspension or engine at all. Unfortunately, this where it all falls apart for me. None of those components do a bad job, per se. There’s just nothing remarkable or memorable about the experience they offer. The suspension, basic as it is with old-fashioned twin-shocks hanging off the end of the swing-arm, works fine, absorbing the undulations of our pock-marked road surface without too much difficulty. Pot-holes are to be avoided, especially with those smaller wheels, but given the superior quality of tarmac available on the continent shouldn’t present a problem while on tour.

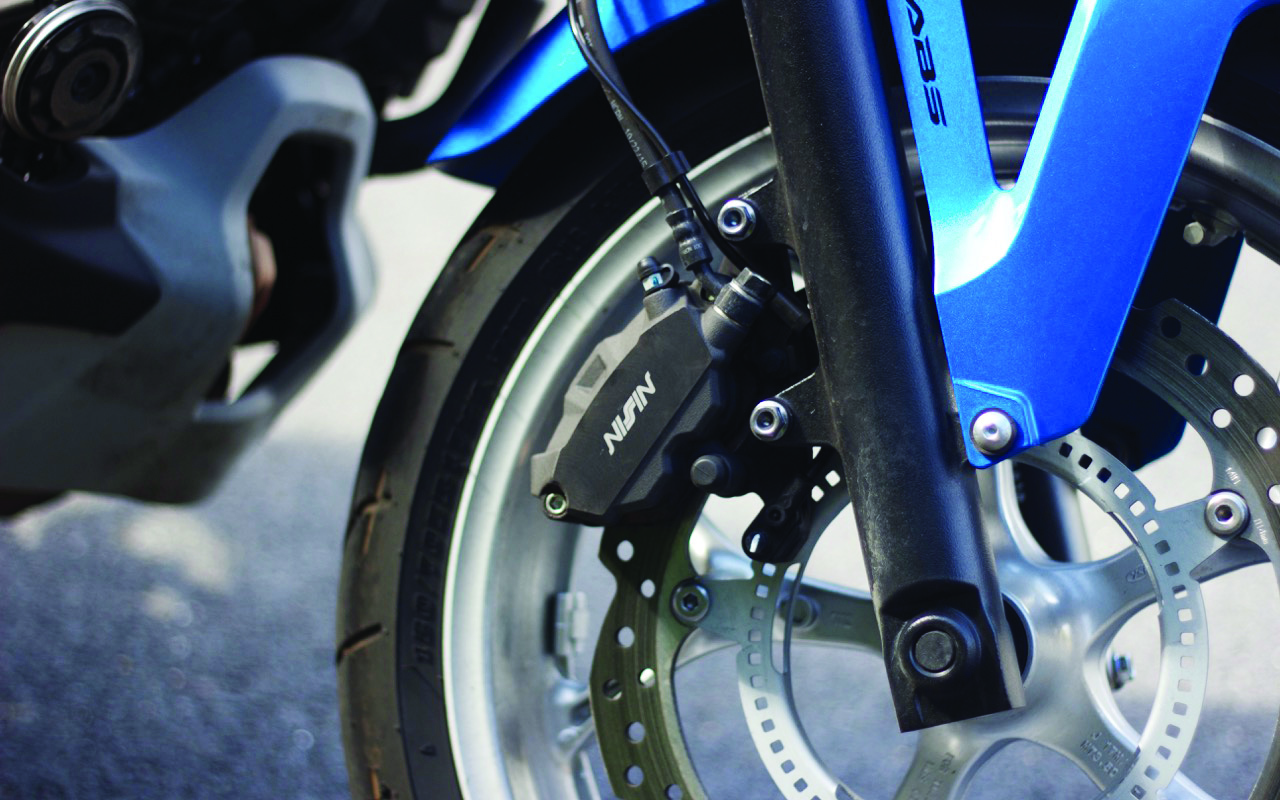

The brakes are odd. Both operated by levers on the bars, the front brake is relatively tame and squishy, the rear biting so hard that it the ABS system can be triggered at will. I quickly reverted to my usual scooter tactic of squeezing both levers hard and genuinely wonder why a single linked lever couldn’t be offered instead. The rear is too sharp to be used for slow-speed manoeuvres, and the smooth engagement of the constantly-variable transmission and automatic clutch mean that U-turns can be executed using throttle alone.

The whole drivetrain, in fact, is utterly unremarkable. If it weren’t for the very faint vibration and low buzz at the edge of earplug-dampened-hearing you could believe that this was Honda’s first electric motorcycle. Torque off the line is smooth and plentiful, tapering off quickly as speeds rise towards the national limit. An indicated 90 is possible, or so I’ve heard from a friend, and if it weren’t for the atrocious windshield the Forza would be perfectly capable of crossing the empty expanses of northern France during the opening salvos of a longer tour.

At lower speeds the throttle response is perfectly judged and the added headroom over lower-capacity scooters means that overtakes are perfectly achievable, albeit with a little more forward planning than is necessary on the 150+bhp monsters many of us are used to. On the other hand, at an impressive 80mpg during mixed riding, as well as cheaper consumables and servicing, it will cost an awful lot less to run than such powerful machines.

While trundling along at 30-40mph is utterly effortless, it’s also utterly forgettable. Riding a bicycle would deliver a more memorable experience than this, and means that what I remember most about those stretches of road is the podcast I was listening to at the time. And that, I’m afraid, means that the Forza 300 fails a critical litmus test in my search for a family touring bike. In its attempts to create a two-wheeler to tempt bored commuters out of their anodyne four-wheeled boxes, Honda has succeeded too well. Even the colour options – mostly various shades of grey – match the soulless identikit cars clogging up our nation’s cities each morning.

All the practical stuff is accomplished with the usual efficiency, and as a way to get to work cheaply and easily I cannot fault it. But I don’t need a commuter. I need a fun-to-use low-speed tourer that will galvanise rather than homogenise every mile ridden, that will add flavour to my travels and become a memorable part of those future adventures. And I’m afraid the Honda Forza 300 fails hard here. My search continues…

Nick Tasker

First published in Slipstream April 2019