After eight years, my 40,000-mile Triumph Street Triple R has gone to a new home. The pandemic didn’t help, but even before the world ground to a halt the annual mileage on my featherweight naked bike was frankly pitiful. In theory, the Triumph fit perfectly into my three-bike garage with its unique selling point of light weight and a unique and raucous engine. If ever my 2012 Suzuki V-Strom 650 or Yamaha T-Max 530 started feeling too sensible, I could take the Triumph out for a spin and sate that particular thirst in short order. So why did I decide to sell it?

The problem is that the roads where I live in Northampton are the opposite of smooth continental tarmac. Even with a fully custom and regularly-serviced suspension, the Triumph made for a very bumpy ride, and I inevitably ended up wishing I’d picked up the keys to the V-Strom instead. And while heading further afield in search of smoother tarmac often rewarded me with memorable riding experiences, there was no getting away from the fact that actually getting to those far-flung roads was never a lot of fun. The last time a friend and I took our Street Triples to the Swiss Alps we both came away agreeing that, while adventure bikes would’ve given up a little bit of pure entertainment value against the raucous sporty triples, they would have repaid that debt a hundred fold in significantly better comfort, convenience, and luggage capacity.

What finally cemented my decision to let go of my well-loved Triumph was that first post-lockdown ride in spring. The engine: incredible. The brakes: fantastic. So wonderfully light and minimalist, with nothing wasted or spare. In a world of electronic rider aids and ride-by-wire throttles, we’ll never see another bike like it. But I’m no collector. Every bike I own has to justify its annual bills, and I can’t afford to keep a bike simply for the sake of a couple of short rides a year. I’m a practical motorcyclist, and my bikes need to be at least a little practical or they gather dust. It also didn’t help that it’s replacement was already parked in the garage.

Regular readers will recall that I tried out Kawasaki’s freshly updated and newly-named Ninja 1000SX last summer. My partner was considering one as a more modern, more practical, and more comfortable replacement for her long-serving 2002 Honda Fireblade 954, and my opinion was sought. As it happened, I loved it – sportsbike looks, but far more upright ergonomics, with a wide, comfortable seat and every modern amenity you could ask for. A big tank, adjustable windshield, and huge lockable panniers meant it could also double up as a touring mount: an area where her Fireblade was inevitably compromised. The Ninja had more than enough power to satisfy on the road, but tuned to deliver endlessly tractable grunt straight off idle with all the smoothness of a well-balanced inline four. I recommended she buy one.

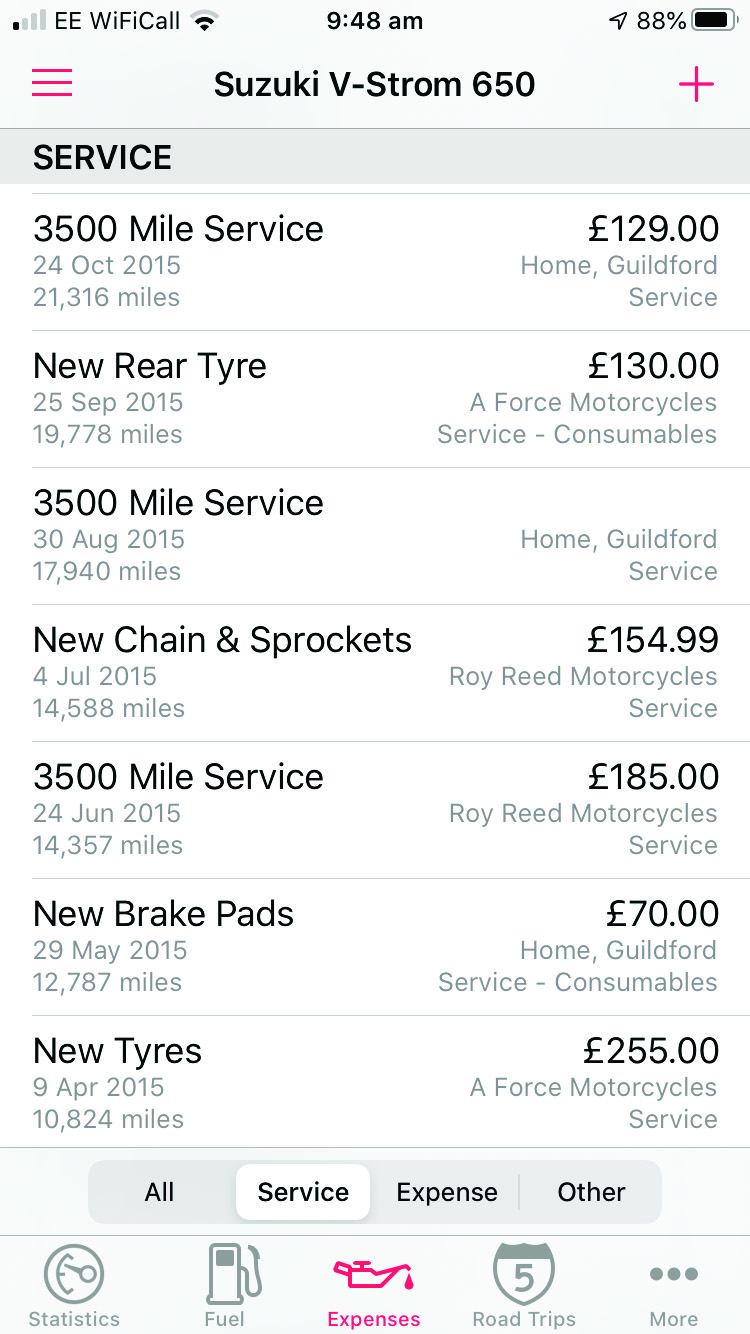

I’ve tested a number of different bikes over the last couple of years, many considered as speculative replacements for my trusty V-Strom, in anticipation of it eventually succumbing to its advancing mileage. And yet, while many had facets that impressed, it was the experience of riding the bright green Ninja that stuck with me. And so, with the V-Strom showing no signs of slowing (and recently conquering some truly gnarly off-road work as part of a 700+ mile weekend in Wales), I began to talk myself into buying a very different kind of motorcycle.

Life is short, if we only ever bought bikes that we needed we’d all be trundling around on perfectly capable Honda CB500Xs. Anything beyond that is excess, frivolity, and can never actually be justified, only desired. I could try, of course. The Kawasaki Ninja 1000SX, with its 140bhp engine, had an almost identical power-to-weight ratio to my 675cc Street Triple, I pointed out. The riding position was almost identical, but with significantly improved weather protection, standard-fit lockable hard luggage, and even cruise control for those long 500-mile days down the French autoroute. It made sense to replace the Triumph with the Kawasaki, to upgrade to something that was better or equal in every way! But in truth, none of that really mattered, mostly, I just really wanted one.

And so I bought one! Or rather, we bought two. A couple of hard-bargaining sessions and one very resigned-looking sales manager later, my partner and I took delivery of a pair of brand-new 2020-model Ninja 1000SX’s in ‘Performance Tourer’ trim – that’s a taller touring screen, colour- and key-coded luggage and liners, some sensible crash bungs, a matching seat cowl, and an Akrapovic silencer. We bargained hard on leftover stock, which turned out to be a smarter move than we’d initially guessed. We later discovered that 2021 stock was being delayed, potentially until very late in the year, thanks to a combination of Brexit, Covid, and the Ever Given and her cargo being held, effectively to ransom, by the Egyptian port authorities. We may very well have the only two ’21-plate Ninjas in the UK right now…

The Windshield

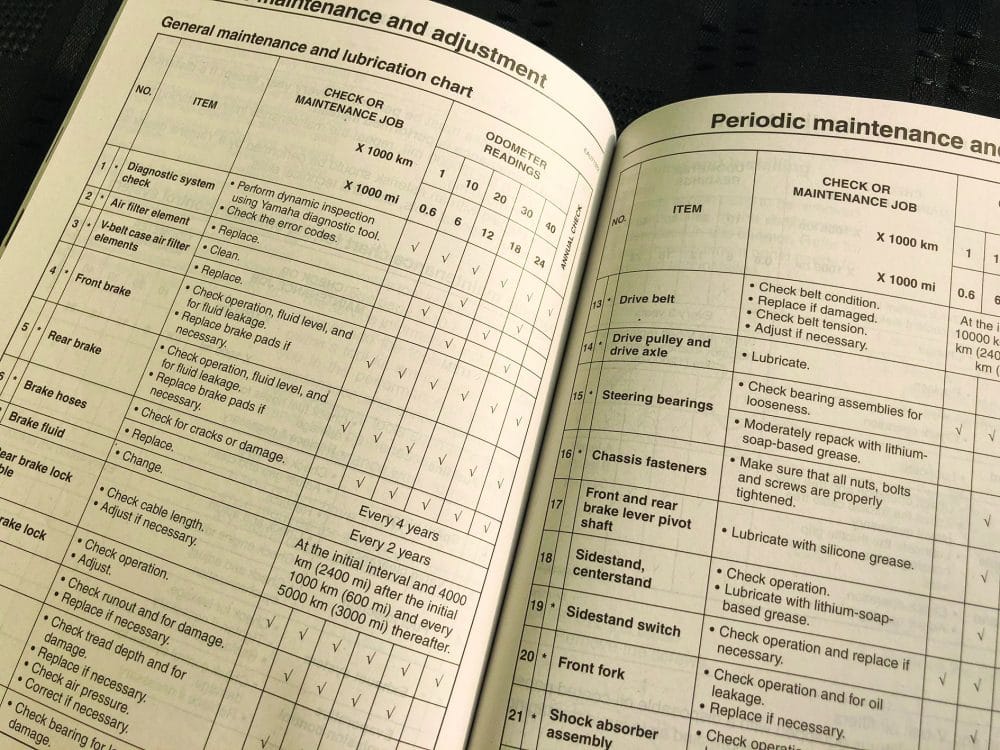

So what’s it like to actually live with a Kawasaki Ninja 1000SX? No matter how experienced at reviewing new motorcycles you are, you still only have a limited time with the machine. Things that seem fine over a few hours or days can come to grate and annoy over hundreds or thousands of miles. And one thing that no-one ever talks about with new bike ownership is the ride-in period, a torturous 600 miles during which you’re forced to ride around at under 4,000 RPM while the super-thin running-in oil finishes honing the cylinder bores. Still, at least now I know that it’s been done properly and should mean many years and tens of thousands of miles of reliable service.

But even before running-in was over and the full rev-range could be unleashed, a couple of surprising issues reared their heads. Checking my own notes from my review last year described a significantly quieter windshield than I was now experiencing, and a notably more comfortable seat. Not only was the touring screen on my new Ninja quite noisy regardless of which position I adjusted it to, but the stock seat proved surprisingly uncomfortable, with numb bum setting in after just 30-45 minutes of riding. What was going on?

Because the ‘Performance Tourer’ spec is merely an accessory pack my dealer provided the original parts, including the standard, slightly shorter windshield. Sure enough, swapping back to the original screen (just four hex bolts) resulted in a much cleaner flow of air, and less noisy turbulence. But something I hadn’t done much testing on during my review was sustained motorway journeys, especially in cold or wet weather, and the shorter screen was directing a lot of cold, wet air onto my upper body. On balance, I’ve returned to the taller screen for the moment, but I may have to look into an aftermarket solution that can be adjusted for height on the go.

The Suspension

While all of this was going on, there was another area that was getting addressed: the suspension. An appointment with my preferred specialist MCT was booked as soon a delivery date was confirmed. Most people probably wouldn’t understand why I’d put time and money aside to fix something that wasn’t really broken, but the truth is that every motorcycle suspension ever made is compromised by its attempts to accommodate the weight of a mythical average rider. I weight 20-30kg less than this target figure, meaning that most bikes are too stiff, delivering a bumpier ride and deflecting easily on the side of the tyre. Oil, springs, and shim stacks are selected at the factory, and while some manufacturers do a better job than others of hitting that one-size-sorta-fits-all sweet-spot, there’s always room for improvement.

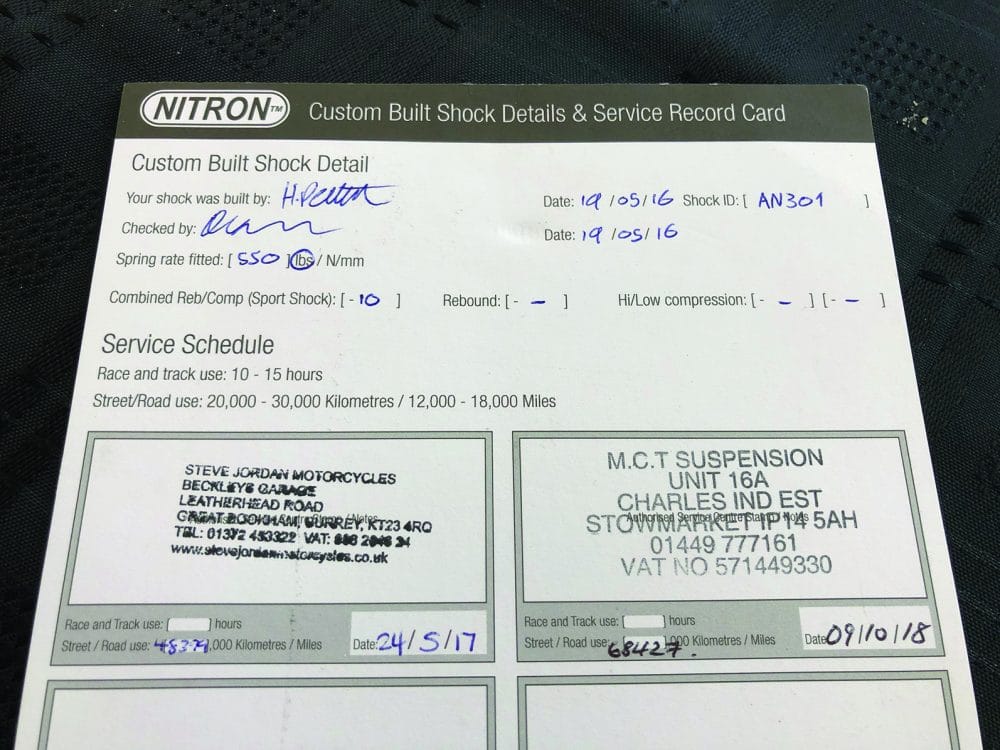

In the case of the Ninja, it turns out Kawasaki did a good job. Darren was able to get the forks spot-on using only the external adjusters, spending a good 20 minutes or so bouncing the front end and measuring responses while he twiddled away with spanners and screwdrivers. The shock was a different matter, with disassembly and a rebuild with a different shim stack required to get good results. I’d asked when making the booking if, like my V-Strom and T-Max, an aftermarket shock would be desirable. But apparently Kawasaki had done a good job here too, cutting very few corners in the manufacture of what would normally be a low-precision mass-manufactured item. I was told that a far cheaper rebuild would deliver results in the same range as a top-quality Nitron, and I never need convincing to save money!

The Other Stuff

Other modifications were smaller in scale, though still important. A 12-volt, 3-amp USB charger wired in to the battery and paired with a new QuadLock mount in the steering stem means that my phone stays charged while playing music and providing satellite navigation on my adventures. A BikeTrac tracker had to be installed by a specialist but will provide peace-of-mind when parked up outside a B&B or Hotel while on tour. It’s entirely transparent in operation, with the system arming and disarming with the ignition key, so you never need to think about it. But if someone tries to move the bike with the ignition off a 24/7 call centre can track the location of the bike anywhere in the world and will alert me (and the police) by text and phone that someone’s making off with my shiny new Ninja.

Paddock stand bobbins are a frustrating necessity for chain maintenance, thanks to the lack of a centre stand. Even an aftermarket option is impossible, owing to the location of the primary exhaust silencer in front of the rear wheel. Kawasaki found a way to solve this problem on their closely-related Versys 1000, so this is certainly an annoying oversight, though not one I can’t work around. Finally, I did briefly have a fender extension installed on the front mudguard to protect the exhaust headers, but despite copious use of the provided double-sided sticky pads it was dislodged and lost after just a couple of dry rides. I should order another, remove the front wheel, brakes, cable guides, reflectors, and mudguard to drill and more securely install it the second time around. But honestly, I’m too busy riding the thing.

The Ride

After 2,000 miles, everything I said about the riding experience in my review last year is still true; it really is an excellent motorcycle for everything from short blasts to day-long trips, with excellent LED headlights making even cold, wet commutes tolerable. I’ve come to the conclusion that the Ninja name is a bit of a misnomer, with the previous Z1000 moniker more accurately reflecting its ‘naked bike with a fairing’ heritage. Try and slice down road with a body-forward position like on a true sportsbike and you’ll find the Ninja to be a bit of an imprecise and overweight handful. Get on top of the flat, raised clip-ons and boss it around like you would a big naked bike and you find making smooth, rapid progress far easier.

The relatively high 235kg kerb weight, though low compared to the big adventure bikes, means that a smoother, flowing riding style is rewarded more than a high-energy stop/turn/go approach. The power reserves may not be prodigious compared to the likes of BMW’s S1000R or XR, but what it gives up in top-end it makes up for in an engine that can pull smoothly from 1,500RPM in sixth gear without so much as a shudder. You can ride in any gear at any speed, the only feedback being a slight turbine-like whine and a satisfying wave of acceleration as you overtake anything on four wheels with ease. Explore the upper third of the rev range and things start to tingle through the seat and bars, with a bit more of a rasp from the otherwise muted airbox. But even wide-open and snapping through the gears with the quickshifter, you never have the same sense of awe and faint terror that you’d get on the old Fireblade. Nor do you get the same raw, angry roar that the Street Triple would emit when encouraged to really let loose, which is definitely something I miss.

The ride-by-wire throttle is direct enough, but the lack of an actual connection to the engine is certainly felt. This is not a fizzing, raucous machine, and were it not for the faint drone of the barely-audible exhaust at idle you could easily be convinced that this was Kawasaki’s first electric drivetrain. I’ve been told that the fully-stock exhaust on my Yamaha T-Max is louder on approach than the Akrapovic silencer of my Ninja, and above walking pace the exhaust is entirely inaudible to the rider. I could invest in the matching set of de-cat headers and associated remap to liberate both noise and an extra 10bhp, or I could embrace the silence, slipping unnoticed between sleepy countryside villages and safe in the knowledge that I’m not going to find myself barred from riding in the increasingly noise-averse Austrian Alps. And with more than double the power of my V-Strom, sometimes its better not to draw attention to oneself.

The brakes are excellent, though I’m sure some more aggressive pads would add a bit of extra bite. The clutch is one-finger light and utterly unnecessary for upshifts, though I need to talk to my dealer about downshifts. In theory the quickshifter should auto-blip and make shifting down through the gears as seamless at it does going upwards. In practice it’s anything but, and you get much smoother changes by dipping the clutch and handling things yourself. I need to find out if I’m expecting too much or if there’s a problem that needs investigating.

The dashboard is easy to read and has all the data even I could wish for, though the interface for changing settings isn’t as intuitive as it could be. In my experience, no-one has figured this one out yet, with both cars and motorcycles either relying on byzantine menus or complicated, memorised combinations of long and short presses of a few multi-function buttons. Resetting the various trip meters on the Ninja 1000SX is a bit like using morse-code to order a takeaway.

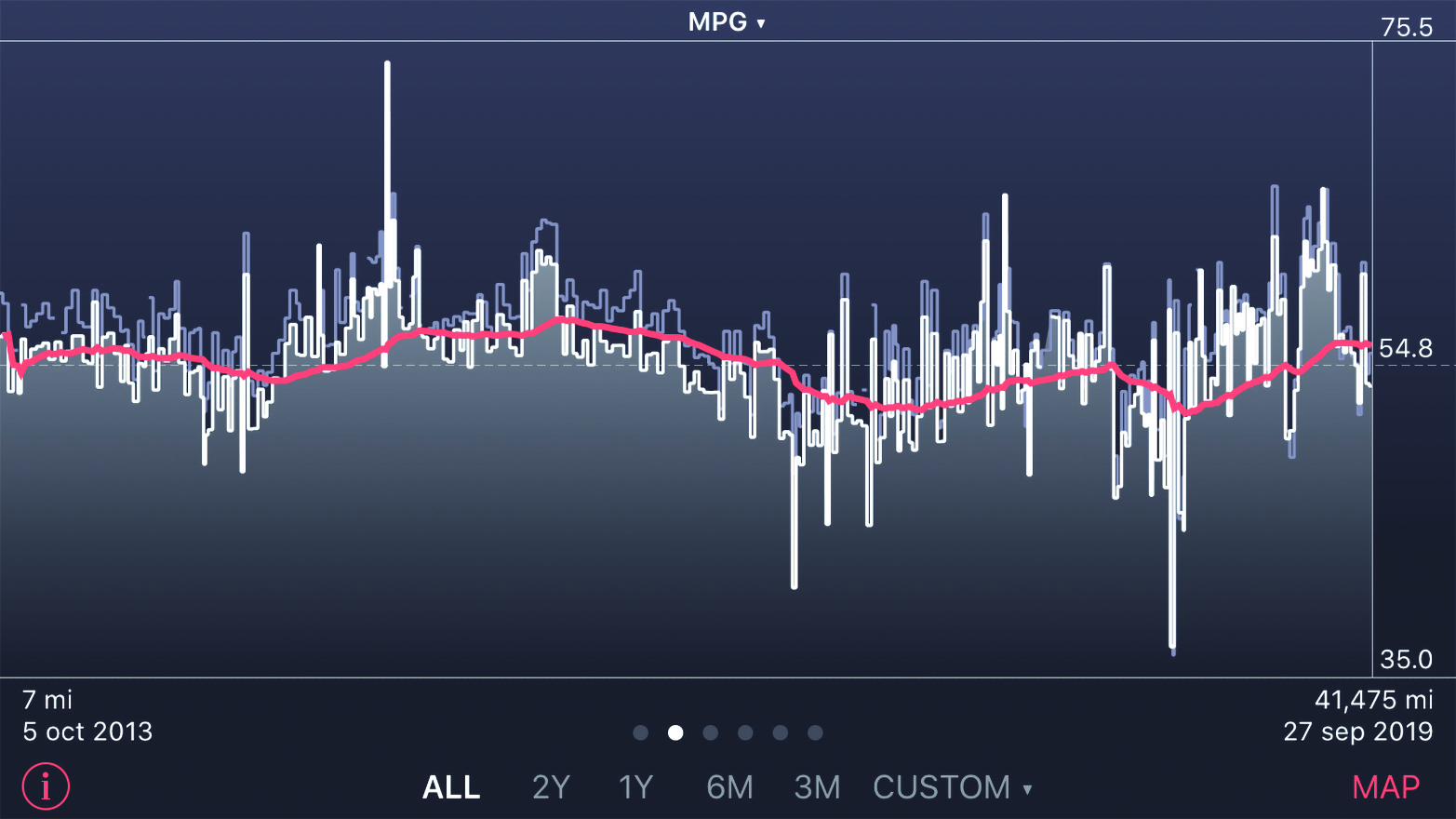

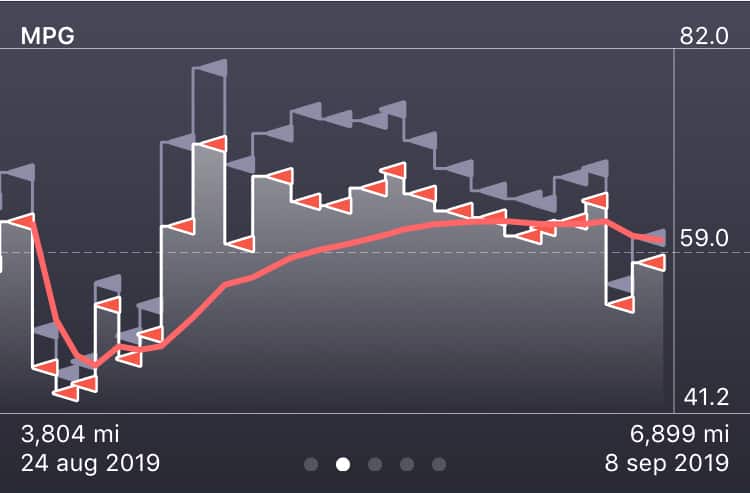

It has to be said, we’re deep in serious nit-pick territory now. The distance-to-empty calculation on the dashboard is utter lies, ambitiously suggesting I can still get more than 100 miles on a quarter tank before rapidly changing its mind as reality begins to bite. In practice, averaging over 50mpg in mixed riding (which is impressive in and of itself) means more than 200 miles between fill-ups. It’s not the 250+ miles I can easily get from the V-Strom, but it’s better than the ~160 miles the T-Max manages. And given what I’ve heard about the new Ducati Multistrada V4’s 35MPG thirst, I’ll take what I can get! Kawasaki claim 19 litres of fuel capacity, but on one rather ambitious run to empty I actually managed to squeeze more than 20 litres under the filler cap, so it sounds like they’re playing the opposite game to Triumph on that score.

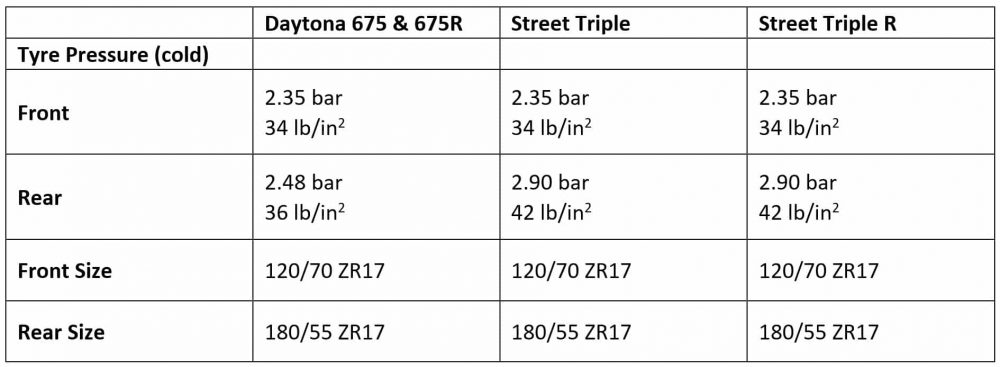

The standard-fit Bridgestone S22’s aren’t fantastic, with questionable cold and wet grip, but at least don’t exhibit any of the handling-blunting traits that OEM rubber reported on other Kawasakis. What looks like a pretty rapid rate of wear may end up being a blessing if I can throw on some Michelin Road 5 or Metzeler Z01 alternatives in short order.

I will admit that, when trickling through slower traffic on the commute, I have wondered if I shouldn’t have taken the time to test out Kawasaki’s closely-related Versys 1000 instead. It’s an even softer version of the same engine hauling around an even heavier chassis, but it does have the more upright ergonomics I enjoy so much in adventure bikes. But once up to speed it matters far less, and the reality is that you never get the same direct connection to the front wheel that inspires so much confidence to press on through a set of risers. But the extra cost of a Versys makes the compromises it offers harder to stomach, and given the fact that I rarely carry a pillion these days, the Ninja still feels like the right choice. And it goes without saying that if I change my mind, you’ll be the first to know.

Until then, I’m looking for every opportunity to get out on the Ninja, but still find my other two bikes receiving regular attention. My three-bike garage now has three sensible, touring-capable motorcycles, all suited to very different kinds of riding, and only time will tell if any of them end up gathering more dust than others. Then again, I do still have a couple of motorcycling niches left to fill…

Nick Tasker

First published in Slipstream July 2021