The “perfect” motorcycle does not exist. This is largely because every rider is different, as is every ride. Break things down to a sufficiently-granular level and we’d each be switching to a different custom-made motorcycle for every stretch of road. At the other end of the spectrum we have a selection of choices in showrooms across the country, all of them heavily compromised to try and be ‘good enough’ for the ‘average rider’. I’ve never met this ‘average rider’, but they’re clearly nothing like me.

That being said, I never expected to be writing an article like this about my 2017 Yamaha T-Max 530 DX. The whole point of buying the most tricked-out version of a relatively high-spec bike is to avoid the need to immediately replace half the parts with better ones. My Suzuki V-Strom was poorly-equipped from the factory but I was able to improve both its performance and my enjoyment through aftermarket upgrades. So why was this necessary on my considerably more expensive T-Max?

Let’s start with the suspension. I mentioned in my 4,000 mile review that it seemed fine, if a little soft in the rear for two-up riding, the centre stand scraping at relatively modest lean angles. Turns out that was only half the story. Since writing that article, Yamaha recalled all of that generation T-Max to replace the centre stand and springs with newly-designed ones. The original design allowed the stand to swing down under the momentum of heavy hits to the suspension instead of keeping it neatly pinned up out of the way, resulting in it scraping when it shouldn’t have. So far, no more scraping.

That being said, a trip to my favourite expert at MCT Suspension confirmed that the rear shock was no good and delivered the bad news that it was not re-buildable, with aftermarket options thin on the ground. I eventually saved up for the only good choice – a custom-made Öhlins unit – but the verdict on the front forks was even more of a surprise. It turned out that the lack of perceived weight transfer was caused by said forks fully compressing almost immediately under any kind of braking inputs, never mind downhill two-up into an Alpine hairpin. The good news was that these were fully re-buildable, being basically R1 cartridge forks, something MCT have a considerable degree of experience with.

The results were, as I should have expected, transformative. Harsh impacts are smoothed out gracefully, with the scooter now feeling lighter on its tyres than ever. There’s more confidence when cornering, more usable feedback from the road surface in all conditions, and less wallowing in high-speed corners. Furthermore, a rear shock is an incredibly easy component to install at home and a great opportunity to clean and grease the linkage bearings. I’ve said it before, but coupled with a good set of tyres a suspension upgrade is some of the best money you will ever spend on your motorcycle.

With the front forks now behaving themselves under braking, the true weakness of the front brakes was exposed. Outright stopping power was there if you hauled on the levers hard, but it was clear that the single-piston rear was having more of an impact than all eight of the R1-spec pistons up front, which made no sense. Braking power was also very difficult to modulate, a typical characteristic trait of squishy rubber brake lines expanding slightly under pressure and creating a less-than-linear hydraulic force delivery.

A new set of braided-steel aftermarket lines would solve this, although in the case of the T-Max that meant disassembling half the motorcycle to extract the five different hoses and shipping them to HEL Performance so that the originals could be measured. This ‘upgrade’, at least, would not be entirely frivolous as Yamaha themselves suggest that the original hoses should be replaced at the four-year mark. Given the unbelievable amount of work this involved, I suspect few other people ever bother.

Next, the brake pads fit as standard to many motorcycles – even performance-oriented models – are a little on the hard side. This means that they last longer, which many owners would appreciate and means that they have a much softer initial bite, and manufacturers claim newbies appreciate. Given that an inexperienced rider’s reaction to poor initial deceleration is usually to panic and grab a whole handful of extra brake, I’m not sure I buy that argument. In any case, I wanted the maximum bite and the maximum braking performance I could get and that meant a new set of high-friction pads. I opted for EBC’s HH formulation, having had good results with them in the past.

The final piece of any brake upgrade is simply a good service. Fresh fluid would happen as part of the hose upgrade – the whole system had to be drained during disassembly. But I also took the opportunity to dismantle the callipers themselves, pulling out and cleaning the internals in the process. The one-piece design means that a special tool is required to unscrew the five-pointed caps from the outside, but once done makes rebuilding the callipers far easier than most. The seals were in good condition and could be reused, but the pistons were filthy and already showing signs of corrosion. Word is that the ones used in R1s are titanium rather than stainless steel and do not suffer the same fate, something I intend to investigate for a future upgrade. But for now, I was able to salvage what was already on hand.

These three jobs done, the T-Max now has the honour of being the best-stopping bike in my garage. Feel, modulation, and power are all first-class, the big scooter now boasting better brakes than even my Kawasaki Ninja 1000 SX. It should come as no surprise that a similar new set of hoses and pads for the Kawasaki are already in the garage and awaiting a quiet weekend…

While I had the T-Max in pieces, I also took the opportunity to remove all the bracketry for the brake lines and have them professionally powder-coated. As you can see from the photograph, both they and the thinly-plated metal parts of the brake lines looked like they had been dredged up from a lake after just a few winter rides and, with the stainless steel HEL hoses holding their own, I didn’t want the badly-corroded brackets to ruin the show. Powder coating is cheap and as you can see, effective.

Electrical upgrades included a 12v charging socket mounted in the battery compartment door, along with a single-led charge-state indicator. I installed the former so that I could have a high-current connection to the battery for my heated jacket and compressor, and to make it easier to plug in a battery maintenance charger. Lockdown effectively killed the (surprisingly expensive) high-capacity lead-acid battery Yamaha shipped the T-Max with and, with a high-tech lithium-iron replacement actually available for less money, I jumped at the chance to shed over 2.5kg from the front of the bike.

A special charger is needed to keep the new battery topped up without blowing it up and I’m advised that I cannot safely jump-start a vehicle with a Li-Fe battery installed, but so far those haven’t been problems. Less successful is the Gammatronix state-of-charge indicator. It technically works perfectly, and I’ve installed them on many other bikes with great success. The idea is that it’s small and unobtrusive, communicating a lot of information with minimum fuss. Solid green means you’re charging the battery at the correct voltage, flashing green means you’re a bit low, flashing orange means you’re properly draining the battery, and solid red means that your rectifier has failed and you should pull over before you fry your bike’s entire electrical system. The problem is that I installed it next to the 12v socket – useful when running a compressor to warn you that you’re flattening the battery, but not exactly in your sight line while riding the bike.

It goes without saying that I switched to better tyres as soon as the original Dunlop Sportmax’s were getting low (around 9,000 miles) and have been much-preferring the Michelin Pilot Road 4 Scooter replacements. They’re fantastic in wet and dry, warm or cold, with neutral turn-in and will hold any line you choose. I suspect they may not last quite as long, and at just under 5k on them I’m not sure I’d attempt a full lap of Scotland as they are now. Frustratingly, Michelin still don’t make a version of their newer Road 5 tyres in the 15″ wheel sizes the T-Max uses, which are pretty unique. I shall have to hope that Michelin keeps making the current versions for a very long time…

The last upgrade I want to mention has been a little bit of a rollercoaster. I like to be able to hear my internal-combustion-engined motorcycles, and given that the T-Max’s 360-degree parallel twin shares the same firing order as my Dad’s Triumph Bonneville, I hoped that a slightly louder exhaust would also deliver its excellent aural component. With the homologated Akrapovic titanium system retailing at over £1,200, I understandably sought out a less official option.

I soon struck gold with a lightly-used IXIL system at a low enough price that it was worth a punt, and sure enough – everything was in the box. What’s more, IXIL are one of the few aftermarket exhaust manufacturers who still equip their full systems with catalytic converters. Seeing as we all have to breathe the same air I prefer to pollute it no more than strictly necessary. Installation was easy, and it sounded pretty good at idle – a nice, purposeful burble. But a few test rides exposed an unexpected problem – it sounded terrible.

You see, the aural interest from an internal combustion exhaust note comes from the variation, specifically how the tone changes as the load on the engine is varied through throttle inputs and engine revs. But the T-Max’s engine load is kept constant at all times through the constantly-variable transmission, and twisting the throttle open further merely increases the engine speed. The result is like the engine note from a racing videogame a couple of decades ago – the same sound effect, looped, and then pitched up and down with no further changes. The ‘upgrade’ hadn’t made the T-Max sound better – it had just made it louder. Less than two days later I refit the original exhaust and put the IXIL system up for sale.

That should have been the end of the exhaust issue, my regular joke now being that I’d actually prefer the T-Max to be quieter, and that I was looking forward to the inevitable hybrid and electric versions. But given my now-apparent intent to keep the bike long-term, I was facing a quandary. You see, for reasons known only to themselves, Yamaha had apparently made the original exhaust system out of poorly-painted mild steel and it was already starting to rust. And so, I returned to my search, this time focusing on trying to find a quiet-as-stock aftermarket system that was made out of something more durable.

Annoyingly, there’s only really one option out there: the aforementioned Akrapovic system. Homologated to be exactly as quiet as the OEM system and made from titanium and carbon fibre, rust would not be an issue. It took more than a year of waiting until a new-in-box example popped up on eBay, courtesy of a Yamaha dealer clearing out old stock in preparation for Christmas. I guess they were sick of it taking up space in their warehouse, and you can tell from a glance at the classifieds that almost no one was willing to pay the recommended retail price when new. So the exhaust was listed at less than half-price, and I was happy to oblige. The original mild-steel system is going to see out one more salty winter, with my shiny new Slovenian exhaust waiting in its box for a quiet weekend in the spring.

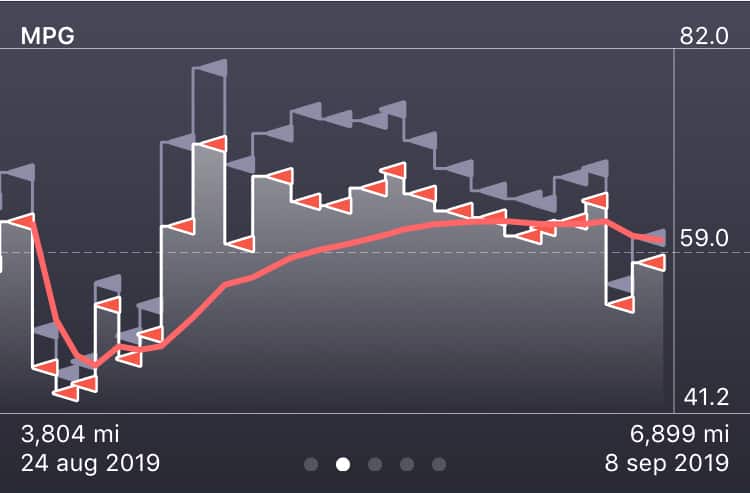

But what of the parts of the bike I haven’t touched? Are they already ‘good enough’ for me, or do I still have further improvements planned? In most cases, it’s that I’ve tried and failed, having found the limits of what I can do with off-the-shelf parts. The fuel range is frustratingly low, and a change in traffic or weather can be the difference between needing to fuel up every time I make the 90-mile round-trip to the office or being able to squeeze in a second day before coasting to the pumps on the way home. The T-Max is so great for long-distance trips that having to start looking for fuel as soon as you hit 140 miles is maddening. Predictably, there are zero manufacturers offering bolt-on aftermarket long-range fuel tanks for such a relatively-niche maxi scooter.

I’d love to move the handlebars further towards the rider, as I’ve done on my V-Strom 650, but closer investigation has revealed this to be prohibitively difficult. Under all that plastic it’s just a standard handlebar in a clamp, so risers would work – but there’s almost zero slack in the myriad cables, wires, and hoses routed to the controls and buttons with which the ‘bars are festooned. Brake hoses and throttle cables are one thing, but splicing and extending dozens of wires to the various multi-function control clusters is a recipe for electrical gremlins. I have decided, for now, to leave matters as they are.

Other issues? Well, I wish that the headlights were brighter, and being LED units already makes further upgrades impossible. Spotlights could be an option, though the lack of anywhere to mount them makes that difficult. More power would always be nice, and in East Asia the popular solution is to fit a tiny little turbocharger directly under the fairing. The results look hilarious, but I’m not sure that I’m quite ready to take such a dramatic step just yet. Yamaha already rebuilt the transmission for me under a recall (belt slippage at high speeds) and I don’t feel like pushing my luck on that score.

Of course, there’s lots that I’ve really come to appreciate about the T-Max. The handlebar-operated handbrake is fantastic for holding the scooter at traffic lights, allowing you to relax both hands and feet while you wait for the light to go green. I wish all my bikes had something similar. I really appreciate the keyless ignition, especially when it means not having to take my gloves off in the rain to fish around for a key. The small wheels and (relatively) short forks mean that the T-Max steers with precision, and you can really place it anywhere you like on the road. You can focus on absolutely nailing your lines through the corners, and with the upgrades to the running gear I never find myself arriving at a curve faster than I or the bike are prepared to deal with.

And what about the recently-updated versions? A couple of years ago Yamaha bumped the engine capacity and somehow the fuel economy, finally switching the remaining front indicator bulbs out for LEDs. This year the bodywork has been thoroughly refined, resulting in a more leant-forward riding position and narrower stand-over. They’ve also retired the two-gauge dashboard in favour of an all-new colour screen, with the option to subscribe for on-screen GPS directions. Of course, I’d have to do pretty much all my upgrades all over again, and the price tags the top-flight versions are commanding at dealers are truly eye-watering. So no – as nice as some of those features would be, I’ll stick with what I’ve got. When Yamaha finally bring out a hybrid version that gets 80mpg and can manage 300 miles to a tank, then we’ll talk.

Nick Tasker

First published in Slipstream March 2022