Impractical, too small, no wind protection…a perfect all-round motorcycle?

Has it really been six years? My RoadTrip report reckons so. It was the 5th of October 2013 when I signed the paperwork and rode away on my brand new Triumph Street Triple R. More than 40,000 miles later the very same motorcycle still sits in my garage, and though the odometer ticks up far more slowly these days, it still puts a smile on my face every time I ride it.

Part of that is down to how light the bike is. Triumph’s engineers shaved several kilos off the Street Triple’s wheels, frame and exhaust system for the 2013 model update, shifting the centre of gravity forwards and creating a bike with the same power to weight ratio as the original Honda Fireblade. 105bhp goes a long way when you only have 180kg to push around, and the lack of weight also helps fuel, tyres and other consumables to last longer when compared with heavier and more powerful motorcycles.

What’s more, this is a bike that seems to be growing in popularity, even as its 765cc successor receives styling tweaks and a price cut for 2020. It’s weird how many people have approached me in recent months to ask me my opinion on the older 675cc Street Triple. Perhaps the fact that the new, 17kg heavier version adds so very little to the experience and costs more than twice what a good-condition used example does has something to do with it. With that in mind, let’s dive into what almost seven years and 40,000 miles can tell prospective buyers about this wonderful little motorcycle.

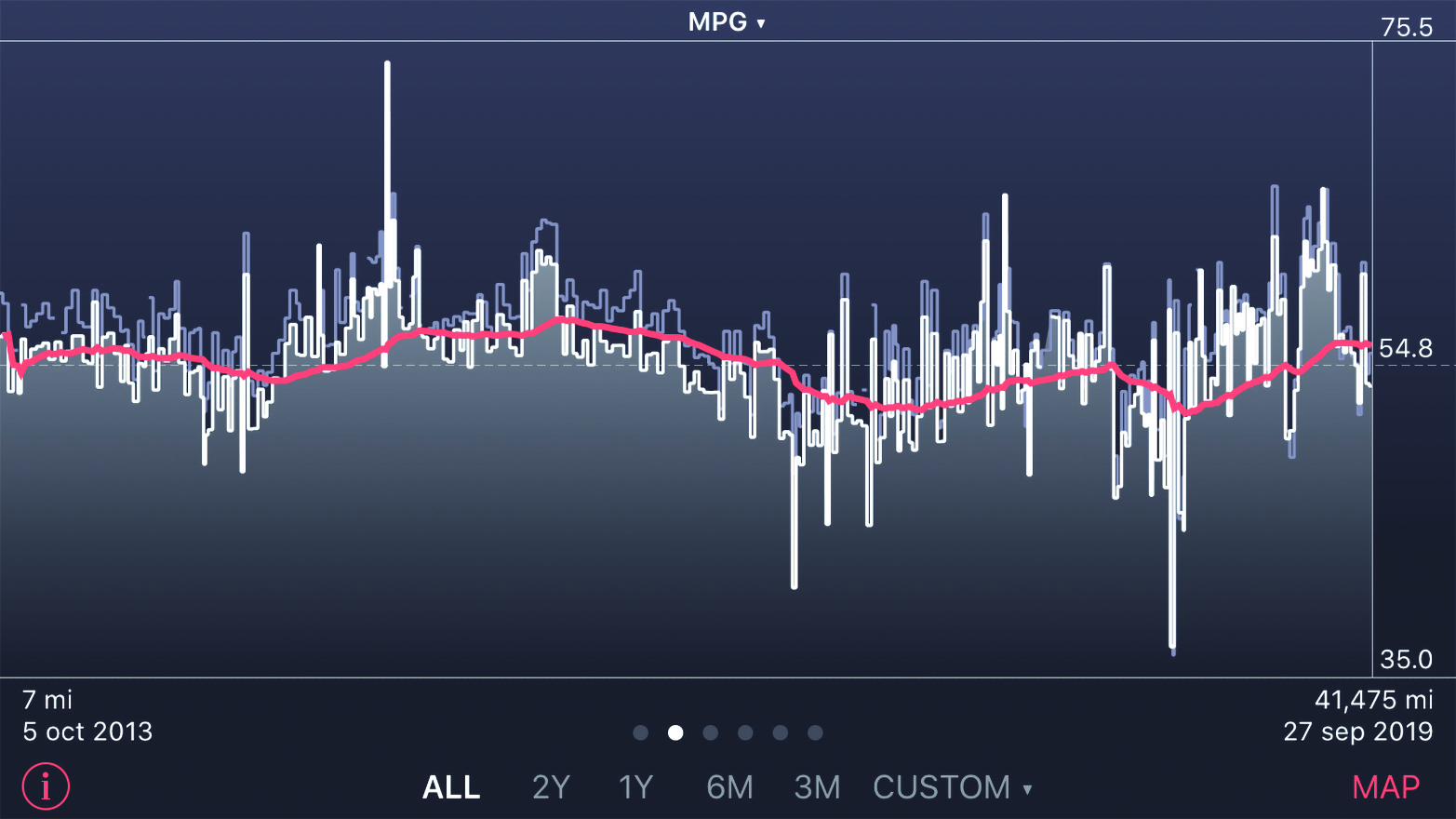

Continuous hard riding pushes MPG down into the mid-40s, but the average is impressive

Firstly, the engine is a delight to use. It’s torquey off-idle and, with practice, you can pull away with barely a hint of the throttle. And yet, it’s smooth all the way to redline with a screaming, snarling exhaust note that puts an inline-four to shame. You can ride around in the middle of the rev range enjoying instant throttle response or waft along in a higher gear returning seriously impressive fuel economy numbers. And with the world moving to bigger, low-revving twins, the joy of a genuinely usable engine that can still rev to 12,500 RPM is something to be savoured.

Brembos would be a little sharper, but there’s honestly no need, even on a racetrack.

The brakes are great; in the years since taking ownership, I’ve had chances to sample some serious Brembo equipment that beat them on both bite and feel, but only by direct back-to-back comparison. Low weight means less mass to stop, and your forearms will give out long before you extract full power from the twin 4-piston Nissins. Triumph equipped the Street Triple R with high-friction sintered-metal brake pads as standard, and it’s the only bike I’ve ever owned where I haven’t felt the need to deviate from the OEM specification.

The fully-adjustable suspension wasn’t quite as great out of the box. As I’ve mentioned many times in previous articles, it doesn’t matter how high-quality or how clever the components are – a stock suspension setup will always be a compromise. The average rider doesn’t really exist, which means that the spring rates and valving will always be set either for someone lighter or heavier than you are. I seriously considered trading the bike in after just a few months because the bucking over bumps and skittering around corners had my confidence in tatters.

When I met Darren from MCT at the London Motorcycle Show and described my symptoms, he was quick to confirm that I wasn’t the first person to bring one of those Street Triples to his attention. He reckoned that there was a design flaw in the forks and that remedial work was necessary. It was an expensive trip, involving modification of the fork internals, but the results were transformative. Suddenly, I was riding what every journalist had promised me I had bought – one of the best-handling motorcycles in the world.

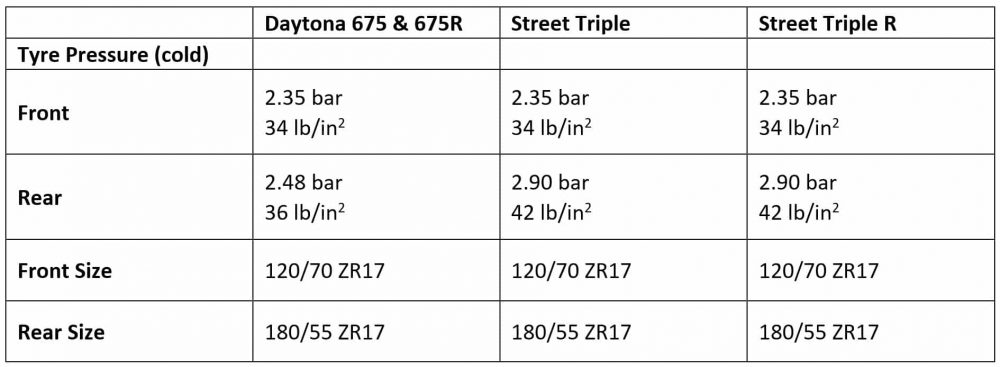

A further tweak was the reduction of the rear tyre pressure after my TVAM Observer commented that the contact patch on my rear wheel looked far too small. Reducing the pressures from the 42PSI indicated in the owner’s manual to the 36PSI recommended for the almost-identical Daytona 675 resulted in a much less skittish rear-end. There was no drop-off in fuel economy, nor an increase in tyre wear, and my only explanation for Triumph stating different pressures for functionally identical motorcycles is to blame their lawyers. With no separate rider/rider-with-pillion pressures listed as with most Japanese motorcycles, I concluded that the Triumph legal team didn’t trust their owners to make the necessary adjustments, and erred on the side of caution when writing the owner’s manual.

Same frame, same wheels, same engine, same suspension… different tyre pressures?

Shaving off several kilos makes a big difference in such a lightweight machine.

The next upgrade, and one I thought long and hard about, was the exhaust system. Believe it or not, the sound or volume was not the primary factor here, rather that the stock system is huge, ugly, and heavy, taking up a surprising amount of space underneath the bike. The catalytic converter is a separate piece from the silencer, so my exhaust emissions remain unchanged, and I’m still within the noise limits for most UK trackdays.

And that’s more or less it! I wanted to keep the bike lean and simple, and resisted excessive modification. I tried a filler-mounted tank bag for a while, experimented with Lomo drybags and eventually settled on a stack of Kriega luggage for my touring needs. A TwistyRide phone mount coupled to a 3A 5V charger handles GPS duties, and a 12V socket wired into the tail unit provides power for a compressor when encountering punctures. And finally, I swapped out the throttle grip for one from a contemporary Speed Triple, reducing the amount of wrist rotation necessary to fully open the throttle. It makes the bike a little snatchy for those not used to it, but means I can enjoy the whole engine, not just the first two thirds.

Without fitting scaffolding to the back of the bike, tailpacks are the only luggage option.

Somewhat disappointingly the paint on the tank quickly became scuffed where textile trousers rubbed on it and the seat has actually cut all the way through to the primer. The official accessory crash-bungs failed miserably at their one job when I finally tipped the bike over at a standstill last year. The indicator hit the ground first, bending the small mounting frame behind the fairing and finally crushing and popping open one of the cells in the radiator. Luckily the plastic pieces weren’t too expensive to replace, and while a new radiator was more than £400, a local specialist was able to repair and clean the old one for a mere £15. There wasn’t a mark on the crash bungs. Useless.

The crash bungs had one job, which they failed to accomplish the only time they were needed.

Other than that, the only issue to report is a hot-starting issue that’s plagued the bike for more than 30,000 miles. Often, when stopping the engine just long enough to fill up with petrol it coughs, splutters and stalls when trying to start again afterwards. It needs a little bit of coaxing and then settles down after a few seconds, but I’ve never been able to figure it out. I recently met another owner who’d experienced an identical issue and traced it to the idle control stepper motor, so maybe I’ll see if I can pick up a used one and swap it out.

Straight bars are a real asset on a tight track like Mallory Park.

And that’s it! With the help of ACF50 my bike commuted through two British winters before the V-Strom took over that job, and the standard-fit stainless bolts are all still shiny. Triumph charged me a fortune for servicing to maintain the two-year warranty, then refused to help when the hot starting issue materialised, so I gave them the finger and have been doing everything myself ever since. Oil changes are easy, but valve checks are a nightmare and due every 12,000 miles, so you’d best hope yours don’t need adjusting! You’d also better have a Windows laptop and a DealerTool handy, as that’s the only way for home mechanics to balance the throttle bodies and reset the service warning indicator.

What of the new 765cc Street Triples that Triumph launched a couple of years ago – am I tempted to upgrade? In a word, no. The resale value of a 40,000 mile Street Triple would barely cover the deposit on the new bikes, and the extra power and needless riding modes don’t interest me. And if you read the small print, you’ll notice that Triumph has started quoting dry weights for their bikes these days, leading some short-sighted journalists to claim that the new bike is slightly lighter than the old one. More recently a magazine actually weighed one and found that the bigger engine and reinforced frame add around 17kg to the total mass, cancelling out the benefit of the more powerful engine.

And in truth, those changes wouldn’t really add to the experience for me. Traction control is always nice, but the fact is that there’s nothing a Street Triple can dish out that modern sport-touring rubber can’t handle, even at a racetrack. If Triumph had made good on their threats to create a version with a half-fairing and hard-luggage, things might have been different. But as it stands, it wouldn’t be much of an upgrade.

Scotland, Belgium, France, Switzerland, Austria, Germany, Luxembourg…

In the last six years I’ve commuted, visited friends and family, travelled the length and breadth of the UK, explored its limits on the racetrack and scraped my pegs around alpine hairpins. It’s handled the Hard Nott Pass and the Nürburgring, moved house with me three times, and eaten 5 sets of tyres. It’s drunk more than 3,400 litres of petrol, chewed up two sets of chains and sprockets, ground down four sets of front brake pads and even worn out a set of front disks.

I’m planning more trackdays, more trips abroad once the present situation opens up the tracks and borders for foreign travel, and still go looking for every opportunity to take my Street Triple R out for a spin on our bumpy local roads now we can get out there again. It’s not as comfortable or practical as my other bikes, it’s not great at motorways or in bad weather, and it’s the worst motorcycle I’ve ever owned for carrying luggage. But with motorcycles getting heavier, with electronics filtering our every input and with the days of new petrol-powered bikes numbered, I’ll treasure my Street Triple R for as long as I possibly can.

I’ll update you all when I hit 100,000 miles, or when it explodes – whichever comes first!

Nick Tasker

First published in Slipstream June 2020