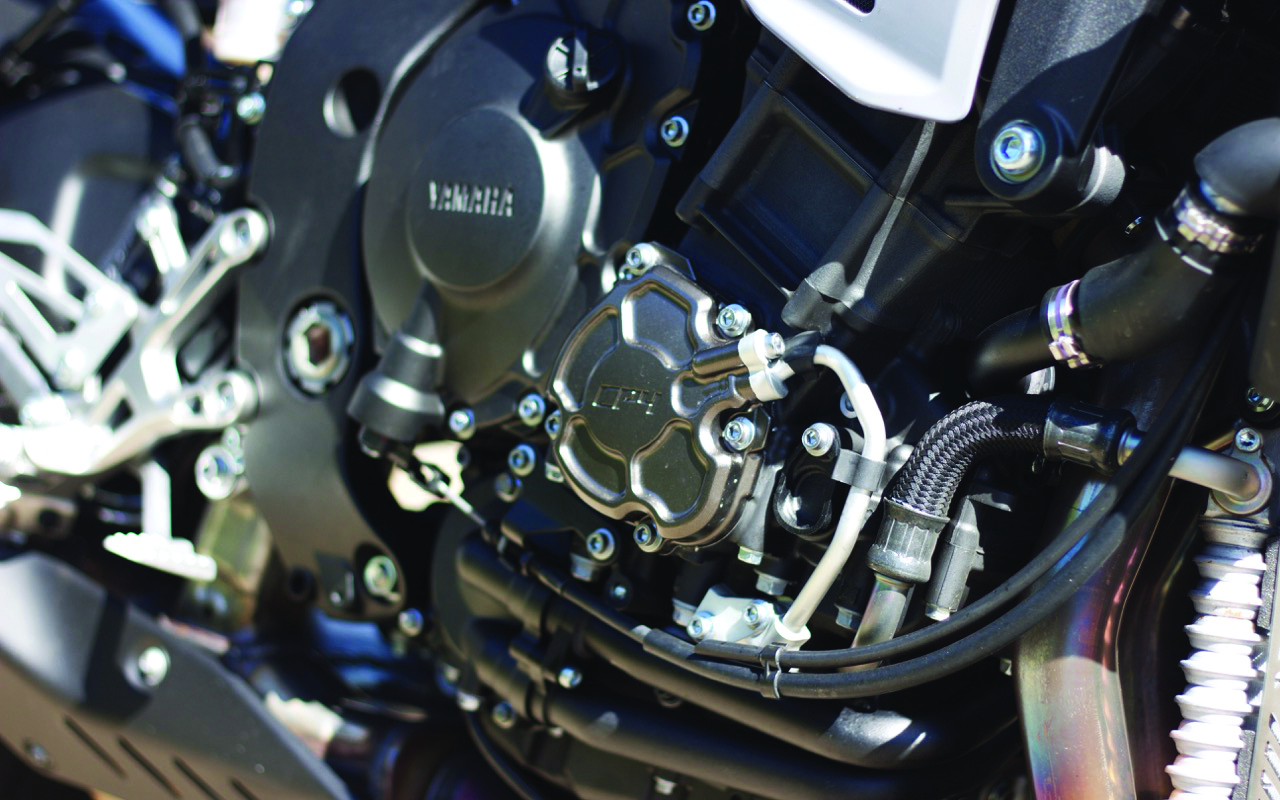

In 2009, Yamaha broke from accepted form by equipping their range-topping litre bike with a cross-plane crank, delivering the sound and power delivery of a V4 in an inline four package. For bikers bored with more than a decade of howling exhaust notes it was a breath of fresh air, adding much-needed aural variety. Since then, more road-oriented riders have been praying for Yamaha to slot the engine into something more upright. Someone in Japan finally listened.

At first glance, you’ll notice that this is no sensible, upright 1000cc Fazer. In fact, at first glance you might lose your lunch, so challenging are the aesthetics. While Japanese naked bikes have become increasingly insect-like in their appearance, many assumed Yamaha would use the more restrained styling evident in the rest of the MT range.

Instead, the MT-10 looks like an R1 was attacked with both an axe and a can of neon spray paint, creating a jagged, sharp-edged, luridly-coloured caricature. This is probably what Michael Bay thinks all motorcycles look like.

Does that mean I hate how it looks? I’m not sure. It does look better in person, and the all-black version looks better again than the grey/neon yellow example I rode. Those headlights are hard work, though. But as I was quickly reminded, you can’t see it while you’re riding it. And the MT-10 really needs to be ridden.

“The MT-10 is a great bike. It’s an incredible machine.”

I’m going to work my way backwards with this one, because it’s a schizophrenic bike. Yes, it looks like it’s just waiting for an opportunity to attack, to throw you into the bushes at the first corner and eat you. But pulling away, the MT-10 is very smooth, very light, and very controllable. It rides beautifully, the quality suspension apparent right away as it takes the edge off potholes and manhole covers while still conveying detailed feedback about grip from the tyres.

In fact, despite its appearance suggesting that the new Yamaha enjoys lurking in dark alleyways to ambush passers-by, you can equip it with a taller screen, hard luggage, hand-guards and heated grips, and go touring. It may not look like it, but this is the promised sensible Fazer replacement, allowing you to cruise to the Isle of Man in relative comfort and practicality before dumping the bags and setting a flying lap around the mountain.

Three different engine modes allow you to choose varying levels of snatchiness, but it won’t present a real problem to anyone acclimatised to a powerful modern fuel-injected engine. Still, the presence of a ride-by-wire throttle suggests this should’ve been taken care of by the software team, and the modes themselves serve little purpose. At least the computer systems mean cruise control and traction control are fitted as standard, and while the former works well, I understandably chose not to try and provoke the latter.

The handling is excellent. It feels quite wide between your knees compared to something like a Street Triple, and it isn’t quite as razor-sharp on turn-in, but it’s not far off. You can exploit the chassis through your favourite bends with minimal effort, but you won’t want to do this for long on the stock seat, which is about as pliable as plywood.

The brakes are, quite frankly, appalling, with zero initial bite and very little power, which comes as a surprise when you see that these are the same radial callipers that can bring the fully-faired R1 to a dead stop with barely a touch. The reason, I’m told, is that Yamaha decided to fit very soft pads to the naked version, and that the problem can be resolved instantly by replacing them with the more aggressive compound found on the sports bike.

This is an odd oversight, given the terrifying amount of speed the 160bhp power plant is capable of inflicting upon you. Let’s be clear for a second – there are most certainly more powerful bikes on the market right now. Yamaha’s Supersport R1, for example, makes 200bhp with the same engine, but the torque is moved much higher up the rev range. I’ve ridden big tourers and adventure bikes with similar power outputs, but the MT-10 weighs just 210kg, giving it a power to weight ratio of 760bhp/tonne. Most supercars barely manage half that.

At 9,000rpm the crank is capable of spitting out 111Nm of torque, but to access that you have to be at full throttle, and that means you’re either already parked in a tree or are hurtling down a long, and crucially straight piece of tarmac, hanging on for dear life as the blurred scenery comes at you all at once. The wide, flat bars and upright seating position mean that merely attempting to exploit the prodigious power available will have the front wheel in the air in the first few gears.

Honestly, I had no idea what I was supposed to do with that engine. Most bikes I’ve ridden get to a point where the wind resistance and gearing effect combine to give a sort of rubber band effect, where opening the throttle no longer causes a linear increase in velocity. Usually this means you’re going too fast, or you’re in the wrong gear. On the MT-10, this simply never happens. If you double the amount of throttle, you will almost instantly double the speed you are travelling.

At anything below the national speed limit, I could reach any speed I chose at any time by barely cracking the throttle a fraction of an inch. This makes fine-grained slow-speed control difficult, and gives the impression of a monstrous attack dog held on a very short leash. I’m sure that cross plane crank sounds amazing once it comes on cam, but there’s just no way to find out; you’ll never rev it that high on public roads. My tester came fitted with a secondary Akropovic silencer, and it was completely wasted.

For years I’ve been confused by motorcyclists who claim they need 150bhp to get the job done. If you or your pillion are starting to bulk up, or if we’re talking about an over-sized touring rig then hauling that extra mass up to cruising speed will certainly require a bit more motive force. But every time I read or hear a motorcyclist comment about sticking a bike in 4th gear and leaving it there all day, I realise that bikers have actually become rather spoilt and lazy.

If a large capacity engine can make enough torque pull stumps at peak, then it’ll make as much power as a small-capacity engine several thousand RPM lower down the rev range. This in turn means that instead of having to use the gearbox to get an engine into the power band, you can just twist the throttle like a scooter and get instant power just off idle. Funny how the demographic that lauds this ability in modern big-bore bikes is the same that raves about the glory days of peaky two-strokes.

The MT-10 is a great bike. It’s an incredible machine. Modern engineering means a large-capacity naked like this can mimic the scalpel-like handling of race bikes from just a few years ago, all with perfect reliability and surprising practicality. But I’m afraid anyone that tells you they can exploit all that power on the road is either lying, or is riding through all their corners in 6th gear.

If you want enough low-down torque that you can leave it in one gear and haul yourself around, Harley-Davidson makes some great bikes that cater to this style of riding. Personally, I’d rather get something smaller, lighter, cheaper to buy and insure, something that can manage better than 39mpg in conservative use, and learn to use the other two thirds of the rev range.

In the first world we’ve become accustomed to being able to comfortably afford far more power than we can possibly use.

The thing to remember is that just because you can doesn’t mean you should.

First published in Slipstream, October 2016