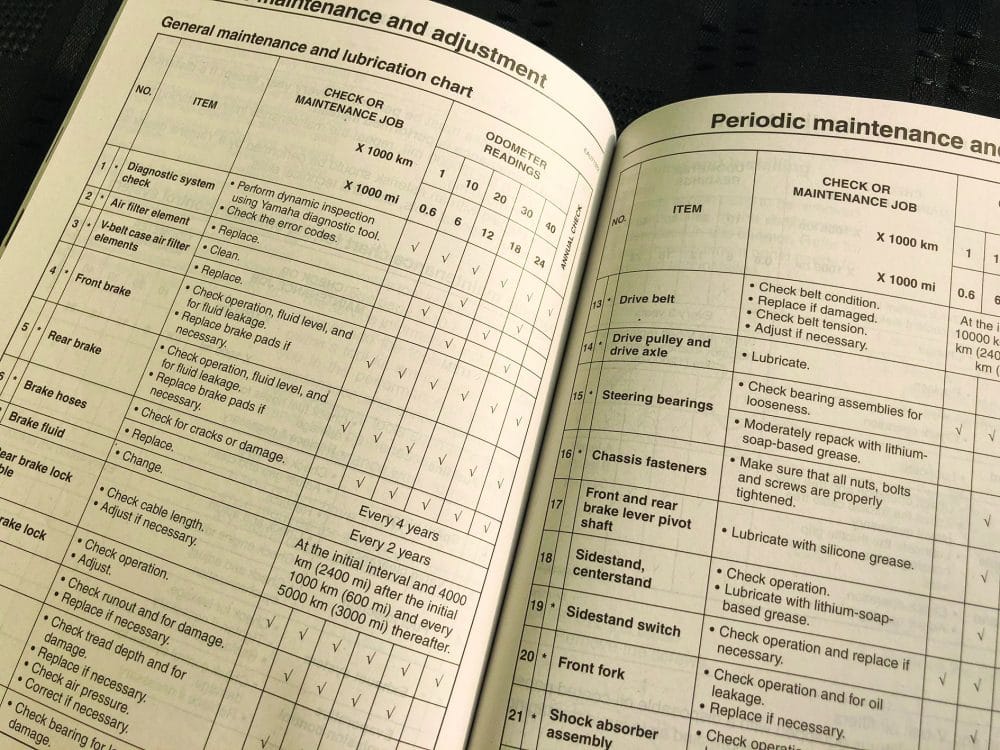

How many of you have ever actually looked at the section of your bike’s owner’s manual titled “Service schedule”? At best, you’ve maybe glanced at the long list, noted the intervals, and made a note to drop your bike off with your dealer or independent mechanic at the specified mileages. The problem with this hands-off approach is that you risk a lot of important stuff getting missed, and suffering the reliability and financial consequences later on.

Whether it’s listed in your manual or not, the official maintenance schedule for your particular model of motorcycle will be defined by your manufacturer. They will have dictated what needs to be done at what mileage and time intervals in order to ensure reliable operation of the machine, or at least to ensure a minimum of warranty claims. The obvious, common stuff will be things like checking and lubricating pivot points (levers, sidestands, foot pegs), checking that no nuts or bolts have vibrated loose, and changing the engine oil. This stuff is easy to do and doesn’t take long, so it’s relatively cheap and makes the customer feel like they’re looking after their bike. Without this work, you’d notice significant degradation in your end-user experience of the product, followed by serious, and easily observable technical faults, such as your engine exploding.

See, long-term reliability and performance isn’t always a priority for the original manufacturer. If you’re a good little customer, you’ll be swapping your bike for a new one every 24-36 months anyway, so any long-term issues won’t crop up under your ownership. If the second or third owner experiences problems, who cares? Those riders aren’t really their customers, so their experience isn’t as important.

Of course, this short-sighted view is why I’d never want to own a BMW or KTM out of warranty but might consider giving Honda, Yamaha, or Suzuki my new-bike money one day. And if no-one wants to buy your used bikes, then suddenly the PCP business model collapses, and your ‘subscribers’ can’t afford your expensive new bikes anymore. But making the maintenance schedule entirely comprehensive would likely hurt new-bike sales. Servicing costs are a significant consideration for many buyers, so Ducati has worked very hard to reduce the frequency with which their bikes need taking in for maintenance. Initial purchase costs can easily be dwarfed by running costs if you’re not careful.

After 33,000 miles, what was left of my V-Strom’s fork oil resembled muddy hot chocolate.

Ask an experienced mechanic what you should be doing regularly to keep your machine at peak performance and you’ll likely be listed a number of things that aren’t on any manufacturer’s maintenance schedule. For example, suspension. Triumph, credit where it’s due, instruct their dealers to change the fork oil as part of regular servicing. Fork oil degrades over time, affecting damping performance, but isn’t considered a service item at all by many manufacturers.

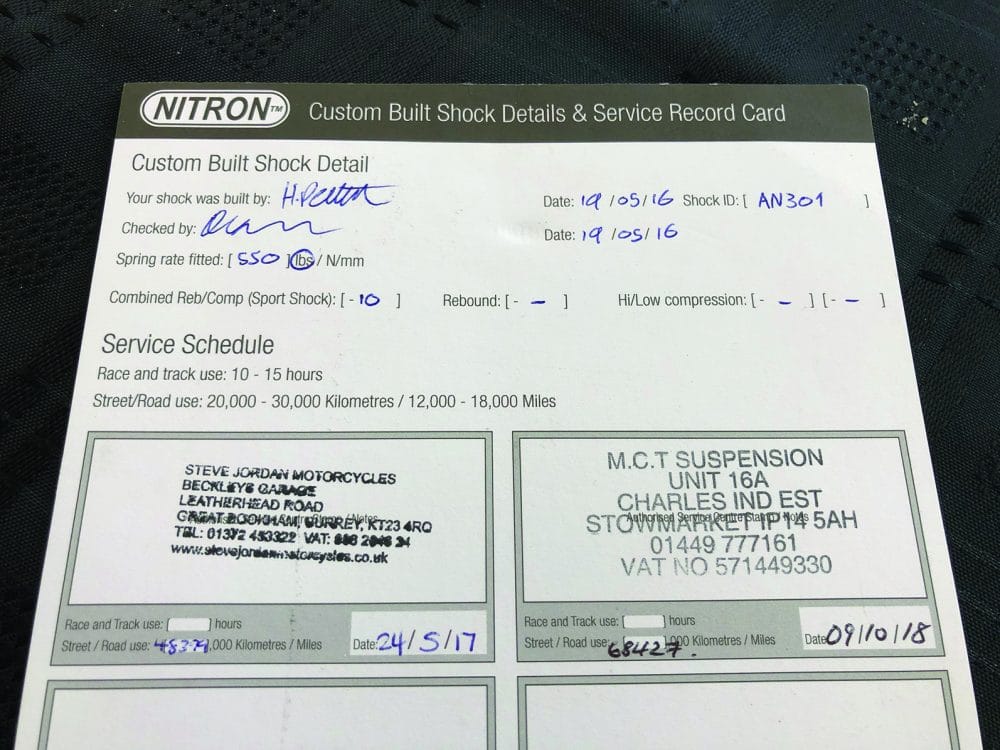

Of course, shock absorbers degrade at the same rate in the same way, and stock units on most bikes are usually not rebuildable. In order to return like-new performance, you’d have to replace the entire shock absorber every 16,000 miles or so. No manufacturer wants to put that on their maintenance schedule, as OEM shock absorbers are hellishly expensive. I once asked a BMW rep at a trade show what their solution was for people wanting to get the suspension on their R1200GS refreshed. With an entirely straight face, he told me that it would never come up because at 18,000 miles I’d naturally be trading the bike for a new one anyway.

Aftermarket shocks can be serviced every 16k miles; stock units can only be replaced.

After a few harsh winters, the running gear under your bike will be in dire need of some TLC.

Staying with suspension for a moment, most modern bikes have complex linkages designed to allow short-stroke shock absorbers to support a wide range of wheel movement. These linkages are usually slung low in the chassis, often placed directly in front of the rear wheel, and get absolutely pelted with rain and salt. What’s more, there’s frequently very little grease pumped into those bearings from new, and after just a few thousand miles of wet-weather use can often by at risk of seizing up and acting against the movement of the suspension.

Because of the torque being applied to these moving parts, it’s rare for a suspension system to seize solid – you simply get metal-on-metal grinding that quickly turns into expensive damage. In the meantime, you’ll experience added stiffness to the ride, but odds are it’ll be so gradual that you won’t notice until it’s too late. Dismantling these linkages can be a very involved job – on a Yamaha FJR1300 you even have to remove the exhaust system – making it very expensive in terms of labour hours.

In a dry climate, with a bike that’s only ridden in nice weather, you could probably go for years and not have a problem. But I’ve taken apart linkages on both my Yamaha T-Max and Suzuki V-Strom when they had relatively low mileages, only to find that I’d caught the problem just in time. One of the linkages on the T-Max was completely seized at less than three years old, and the bearings all showed tell-tale signs of rust. This premium scooter had a full dealer history when I bought it, but nowhere in the maintenance schedule are suspension linkages mentioned at all. But worst of all is when stuff is on the service schedule, but lazy mechanics don’t do it because it’s too much work. Depending on how honest your mechanic is, you might still be paying for the work, but I have strong evidence to suggest that my Triumph dealer never checked the valve clearances during my Street Triple’s 12,000-mile service, despite charging me for the work. “Everything was fine, nothing needed adjusting, that’s 3 hour’s labour please.” I can almost understand the logic; if you’ve checked dozens of engines and they’ve thus far been in-spec at the 12k mark, then it’s very tempting to assume that they’ll all be fine. But you can’t officially not do it, or the manufacturer will blame your dealership if there’s an engine failure under warranty. So you tick the box and move on to the next bike on your to-do list.

Steering head bearings are a similar story. Buried under fairing on many bikes, and requiring hours’ of work to get to even on unfaired models, checking, re-greasing and adjusting them must be a task that’s tempting to ignore. And how would the customer even know, one way or another? Steering head bearings can fail at any time, even if well maintained, and are considered a wear item. No warranty claims, no proof, no problem!

Getting to the steering head bearings is no mean feat, even on a naked bike…

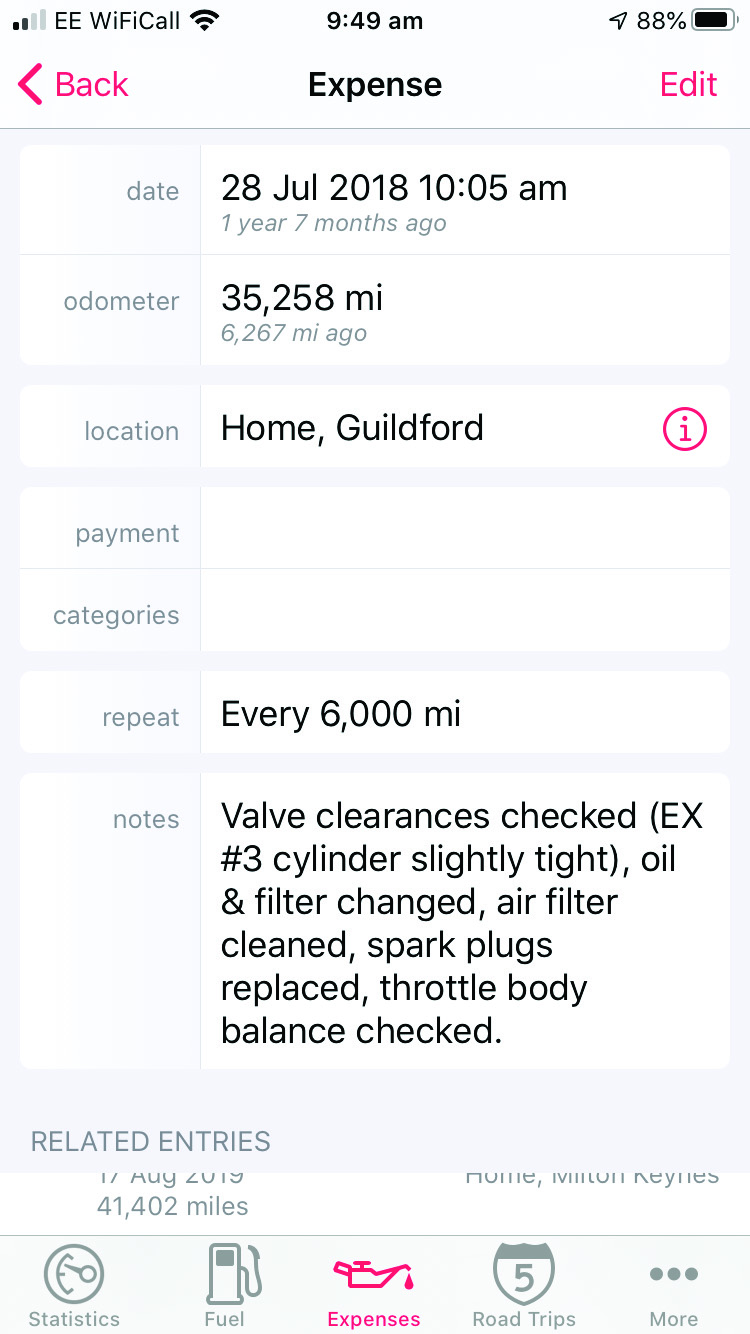

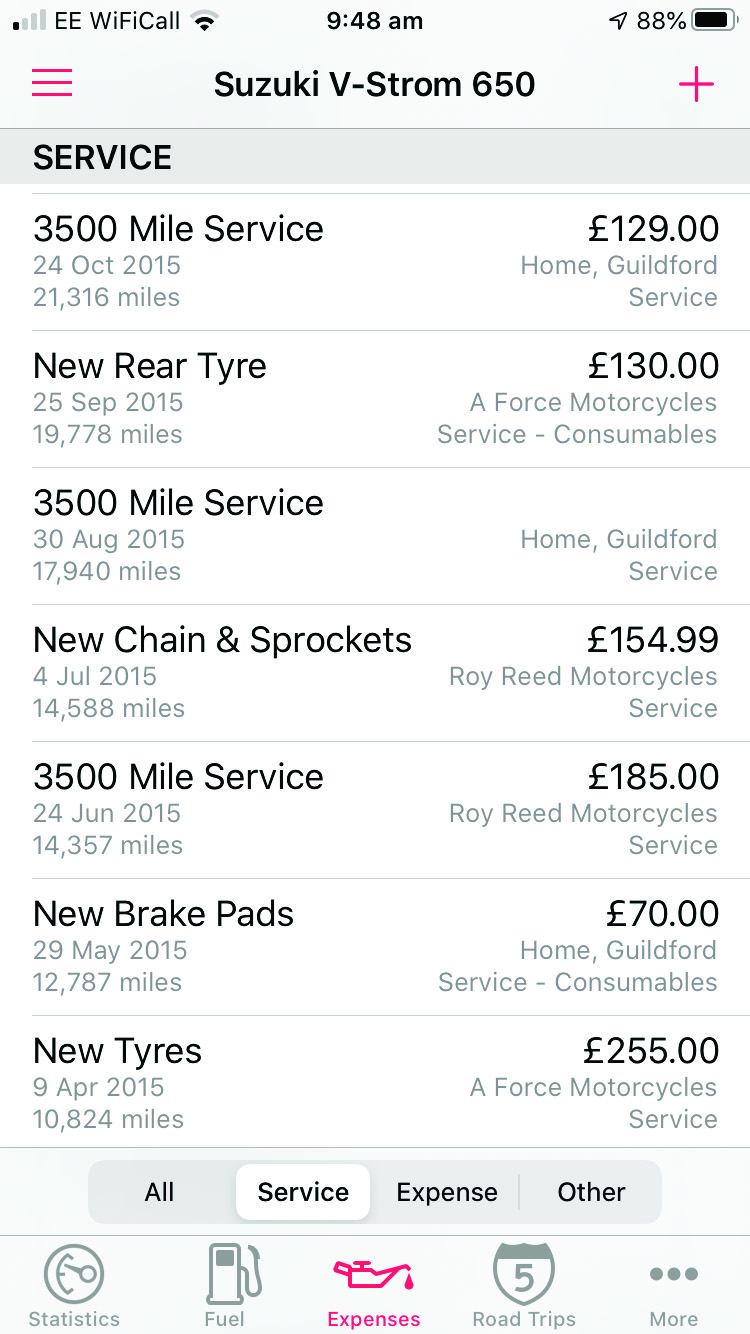

The next problem you have is detailed service records, or the lack thereof. If you’re taking your bike back to the same main dealer, or a dealer with access to a shared records system, you might be OK. They’ll be able to look up what was done last visit and therefore know what is required this time, be it an annual service or something mileage-based. If you’re relying on a different dealer or a mechanic that simply doesn’t keep those kinds of detailed records, you’ve got a problem. You’ll have a stamp in the book showing when the last service was completed, but no details of what work was completed. So the mechanic will ask you what needs doing this time, and unless you’re like me and keep track of individual service items yourself, you’ll have no idea.

Is it time for the brake fluid to be changed? The fuel hoses to be swapped? Are you due a valve check or not? Some items are time-based, others on mileage alone, some a combination. Asking a mechanic to “service” your bike is like asking an artist to paint you a picture – you’re going to need to be a lot more specific. Asking for a “basic service” usually means changing the engine oil and filter, maybe an air filter, a check of the brakes, followed by a quick once-over to make sure nothing external is leaking or otherwise obviously broken. Do that same thing every year or every mileage interval and you’ll probably avoid catastrophic engine failure and maintain basic safety, but long-term reliability and performance will suffer, and you could be storing up some big, expensive repair bills for the future.

My approach is to meticulously document everything

Here are a couple of tips and best practices I’ve developed over the years:

- Keep detailed service records of exactly what was done and when. Ask your mechanic or service writer for a full breakdown when you pay the bill.

- If using an independent mechanic, do your homework and get hold of an itemised service schedule for your bike. If they are true professionals, they won’t mind looking at the previous work notes and official service schedule before talking to you about what they recommend needs doing based on your bike’s history.

- Use forums and owner’s clubs to find out if there are any model-specific maintenance pieces that should really be added to the manufacturer’s list of service items. Discuss these items with your mechanic, with a view to seeking their advice – no mechanic wants to think that their experience is valued less than “wot I read on the internet”, so be diplomatic.

- Find a mechanic you can trust and stick with them, making sure they understand that you’ll be using their services again. If they’re going to have to pick up the pieces of any corner-cutting, they’ll be less likely to cut those corners in the first place.

- If you intend to keep the bike for the long-haul, let your mechanic know. The advice they would give to someone looking to keep a bike short-term might well differ from what they would tell someone who wants to still be relying on the same machine in 50,000 miles.

- Have any particular maintenance tasks you think are frequently overlooked, or maybe a particularly clever way of logging everything? Send me a message and let me know!

Nick Tasker

First published in Slipstream April 2020