Remember when the Dacia Sandero launched in the UK? It made a big splash in the automotive press and even beyond; an actual, proper car for just £6,000. With the competition priced close to three times that amount it was no surprise that a lot of people picked one up almost on impulse. Once things calmed down a bit, the more serious, cynical journalists got their hands on them. Eventually a consensus was reached that, while you could buy a new car for just six grand, you could also buy a much nicer used car for around the same money.

My suspicion is that the Royal Enfield Himalayan might suffer a similar fate. Right now, we’re all going crazy for the things and, on paper, it’s easy to see why. A brand-new air/oil-cooled 411cc single with a low seat height, genuine off-road capability, and impressive luggage capacity for just £4,200 on the road? Surely there must have been a mistake? The internet is already awash with videos of people loading them to the gills, throwing on a set of serious knobbly tyres and tearing off into the wilderness; the big-dollar BMW/KTM/Triumph adventuring experience for a quarter of the price.

While at our local Royal Enfield dealer, I saw a chap pull up on a Himalayan wearing what looked like a full set of very clean BMW adventure textiles. It occurred to me that someone who had already signed on the dotted line for a motorcycle that was just a few accessories short of costing £20,000 would probably not be too keen on risking their expensive new machine down a rutted country lane. One mistake, one surprise rock or rut and the repair bills could easily be in excess of what a whole Himalayan costs to buy outright. And so, in a way, this new Indian-made motorcycle might simply be the world’s most expensive set of crash bars.

Those of you who have recently sat down with a salesman in a European motorcycle dealership will have noted how little adding thousands of pounds of electronic suspension, heated seats and aluminium panniers seems to add to the proposed monthly payment. I can’t help but wonder how long it will be before some enterprising BMW dealership starts offering to roll a whole second motorcycle into that 3-year plan.

But does the Himalayan deserve better than this? Can it stand alone as a perfectly good motorcycle, a worthy competitor to our overwrought, over-complicated and over-priced Japanese and European machinery? Have the Indian-owned Royal Enfield finally got the hang of quality control and delivered a reliable, dependable, rugged motorcycle that we can be proud to put in our garages?

Judging that last point is normally very difficult on a carefully-controlled test-ride. Manufacturers, and by extension, their dealers, are understandably very careful to ensure that a potential customer has a flawless introductory experience that will encourage them to hand over their credit card at the end. Fortunately, the Himalayans we took out obliged by breaking down almost immediately, thereby putting the matter to rest.

My brother’s bike decided that throttles were for wimps and wedged itself wide open, refusing to be fixed and needing to be coaxed back to the dealership with the clutch. In addition, neither of us could read half of our instruments due to the significant condensation behind the glass on the displays – a common issue, according to the internet, and apparently preventable by greasing all the connectors to the clocks, but still not really something I would expect to have to do on a new machine.

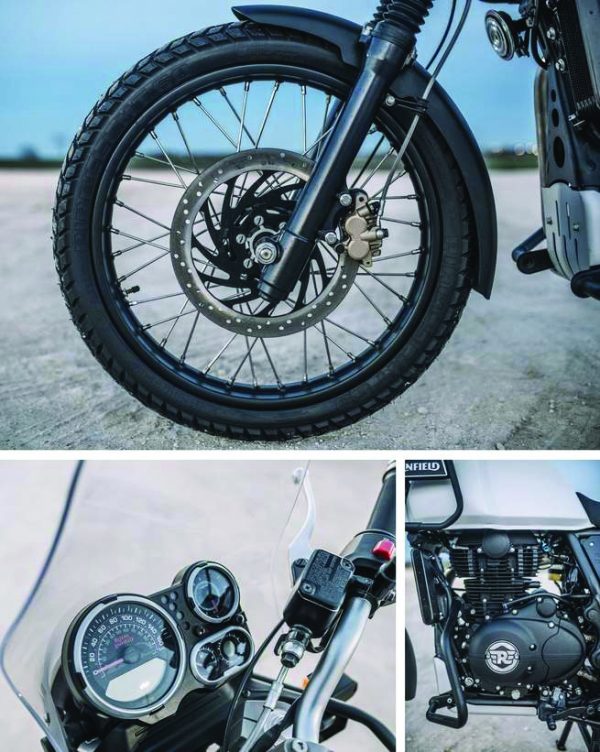

The next black mark was for the brakes. We both discovered that stopping distances were far, far greater than we would expect, and had to haul on both lever and pedal rather brutally to prevent obstacles in front causing unplanned wheelbase reductions. The front brake has no feel and no bite, requiring the rider to simply squeeze the lever as hard as they can as far in advance as possible. The rear is the opposite – loads of feel and bite, but it locks up almost immediately, causing the ABS to cut power to the brake and rendering it essentially inoperative. It’s possible that the softer brakes might be ideal for use in dirt or gravel but on the road they’re simply not fit for purpose. Better pads might help, but again, it’s something that should have been resolved at the factory.

Things start looking better as we work our way down the parts list. The seat is surprisingly comfortable – even for pillions – and the riding position somehow works well both when sat down or stood up on the pegs. Combine that with an extremely low seat height that would allow most riders to rest both feet flat on the ground yet miraculously fails to result in my knees sticking up around my ears while on the move. Our shortened ride time did mean that an extended test would be required to confirm if things remained comfortable for longer trips.

The suspension was soft, but not sloppy, and probably a good fit for the sort of riding this bike was designed for. I’m quite sure that the higher cornering speeds possible with better tyres might cause wallowing but achieving those high speeds would be a challenge with the meagre 24bhp on offer.

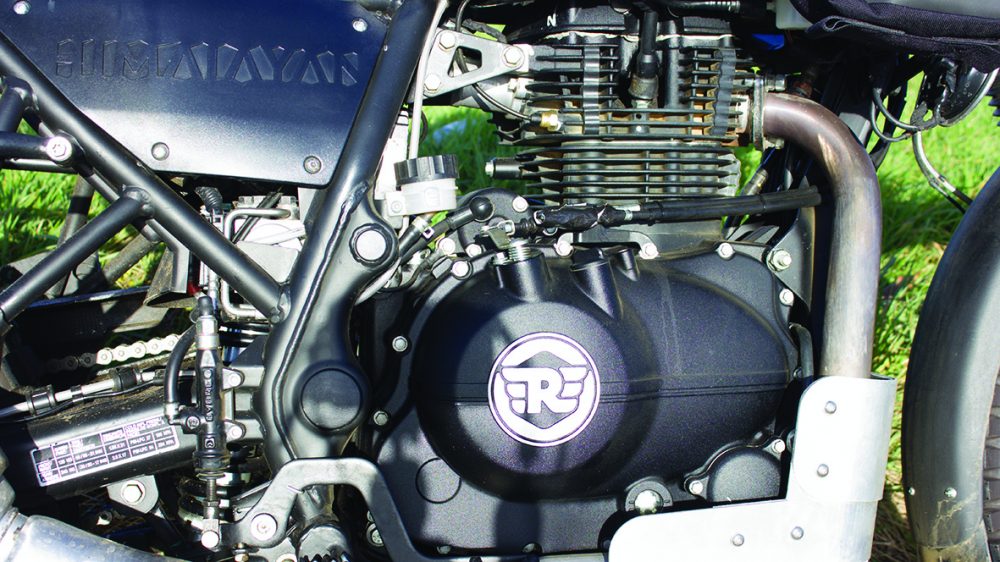

That’s not to say that the Himalayan feels slow, as long as your expectations are realistic. The 411cc air/oil-cooled engine is surprisingly smooth and relatively punchy, feeling more like a slightly breathless V-twin than a thrashy single. There’s not a whole lot going on below 4,000rpm, even if it’s more tractable than plenty of larger multi-cylinder bikes I’ve ridden, but the show’s all over before the needle reaches 6K. Even then you can feel valve float setting in and distressing noises can be heard from the top-end before the tachometer is past 5,500, so the usable power band is surprisingly narrow. It’s just as well that the gear shift is accurate and the clutch light, as you’ll be using both frequently.

Speaking of the clutch, one modification I would have to do on day one would be an adjustable lever. The biting point on the Royal Enfield is somewhere just beyond my fingertips, meaning that those of us with smaller hands may find pulling away from a stop a matter of setting the revs and just letting go of the clutch entirely. The soft bite and small displacement mean that setting off isn’t too bad but low-speed manoeuvres inevitably lack accuracy.

Other than that, it has to be said that niggles, irritations and deal-breakers are notable by their absence. The Himalayan may not do anything spectacularly well, but neither does it fall noticeably short anywhere. The footpegs don’t get in your way when you set your feet down, and the side stand is easy to extend and retract, two tricks that plenty of bikes costing 3-4 times as much somehow struggle with. The windshield is well designed, if a little too short, and a small fairing would make motorway stints entirely manageable.

As standard it comes fitted with a pair of practical tank-mounted pannier rails, with an optional rear-mounted set and matching metal panniers available from your local dealer at a refreshingly low cost. The dashboard is fully-featured, offering an analogue tachometer and speedometer as well as various trip meters and even a compass – something I cannot recall having ever seen before on a production motorcycle. So far owners have been averaging almost 80mpg in mixed use, meaning that a 250-mile range is easily achievable from the relatively meagre 15 litre tank.

I would prefer to reserve judgement until I’ve had more time in the saddle, but my brother feels that the only test ride long enough would involve multiple border crossings and a few months of atmospheric exposure. All the enthusiastic video reviews online seem to be shot in the driest, dustiest parts of Utah or Arizona, and I can’t help but wonder how well this machine would survive a couple of wet British winters. Used Bullet 500’s seem to be either immaculate fair-weather bar-hoppers, or look like they’ve been dredged up from the bottom of a river.

The Honda CRF250L would come close for entry-level dirt capability, although luggage and pillion capability are comparatively non-existent. Triumph or Ducati’s latest small-capacity Scramblers would be just as capable off-road and far better on it, but are double the price. In fact, the biggest competition for this £4,000 new motorcycle is a £4,000 used motorcycle. And that is where, test-rides or not, things fall apart rather upsettingly for the Himalayan.

You see, you can buy a whole raft of used mid-capacity adventure bikes for around the same price and, with matching dirt-oriented tyres, would be no less capable off-road than the small-capacity Royal Enfield. There’s nowhere that I would take a Himalayan that I wouldn’t take my V-Strom 650 and you can buy those for £3k. It wouldn’t be new and it wouldn’t be covered under a warranty but experience has shown me that you wouldn’t actually need one in any case. It would shrug off a few winters, be more competent during the tarmac sections of your trip, and would likely feature fewer pre-existing issues that required your immediate attention.

Certainly, a BMW F700GS or Triumph Tiger 800 would weigh more than the Himalayan, but not by much – the small 411cc single manages to tip the scales at a surprisingly heavy 190kg. If the low seat height is what caught your attention, then might I suggest you leave the majority of your budget in your pocket and pick up an early Honda CB500 instead? Similar weight to the Enfield, similar seat height, but with double the cylinders, power and torque. Bolt on a set of crash bars, lever on some Mitas E7’s and hit the trails.

I think that the Royal Enfield Himalayan’s biggest triumph may be to demonstrate conclusively to the rest of us that you can take pretty much any bike anywhere as long as you don’t care if it gets a little beat up. It has reminded us that most off-roading is actually just gravel roads with a bit of grass; trails that do not require any of the trappings of a serious enduro machine.

There’s a chap circumnavigating the globe right now on a Ducati Scrambler – a motorcycle roundly mocked by off-road enthusiasts as a poser/hipster/city bike – and Nick Sanders has toured the length of Africa on a Yamaha R1. Charlie and Ewan took BMW R1150GS’s on their famous cross-continental adventures, but their cameraman got stuck far less on the piece-of-junk Russian motorcycle he picked up at a local market. As far as I can tell, the biggest problem the Royal Enfield Himalayan has is that we don’t actually need it.

Nick Tasker

First published in Slipstream January 2019