Having seen a fair amount of Europe on the bike, I was keen to venture a little further from home. Morocco had really appealed to me for some time, mainly because I had absolutely no idea what to expect. I booked three weeks off work and set sail on the Santander ferry from Plymouth. Not owning a ‘proper’ adventure bike, the trip was done on my Yamaha FZ8. Absolutely no off-road capability, questionable luggage-carrying capacity, and high mileage from being used as my commuter made it an interesting choice, but it had two wheels and an engine so it was good enough for me. Also, it was my only option!

Rif mountains.

The first part of the trip was fairly standard, the 24-hour crossing the Bay of Biscay, then making my way down through Spain, stopping in Burgos, Madrid, Malaga and finally in Algeciras. I had made the decision not to camp on this trip so was booking cheap hostels along the way. Algeciras was the destination as it was here I planned to make the crossing to Africa. On approach to the port town there are dozens of kiosks and travel agents advertising crossings to Tangier Med, meaning there is no need to book from home and making it very easy to remain flexible. I was lucky enough to find a very helpful agent who booked me a flexible ticket both ways and even threw in a free bottle of wine. I chose a cheap hostel overlooking the port and took an early crossing the next day.

My first night’s accommodation was in Chefchaouen, the ‘blue city’. I had met up with another solo traveller on the ferry and we decided to grab lunch in Tangier, a 45km drive around the N16 coastal road from Tangier Med. The first five miles out of Tangier Med make you feel a long way from home – just two hours on a ferry and you have arrived in a totally different world. The crowds lining the sides of the main roads, the small shacks and the barren landscape are a far cry from the relative greenery and affluence you left behind in Western Europe a few hours ago. Shortly after, we went our separate ways and I joined the N2, winding my way through the northern Rif Mountains into the touristy blue town. On arrival in Chefchaouen, and like most major towns and cities, you are unable to get anywhere near the centre with your vehicle, which is where most of the hotels are. Tipping a local to help you find a safe spot for the bike and your way to the hotel is a wise move, as the old streets can be maze like.

Todra river.

One night in the blue city was more than enough. The town that looks so idyllic on Instagram exposed as some old building painted blue in real life, and the small narrow streets are plagued by tourist overcrowding. I took the backroads to Fes from here, avoiding the signposted main roads and opting instead for the R408, a very rural back route.

This was a good move as it was quiet, beautiful and full of small communities where you see the real Morocco. Stopping anywhere near these villages attracts a crowd in seconds which at first can seem intimidating, but you soon realise that the locals just want to say hi and be friendly.

Arriving in Fes, I was hailed by a parking attendant and ushered into his car park. This seemed a bit of a con at first, but I accepted, paid and tipped him an extra 10 Dirham (80 pence) to look after my bike whilst I spent a couple of days in the city. This tip turned out to be the bargain of the holiday. On my return he was very proud to show me that he had remodelled his corrugated iron barn around my chained-up bike. Slightly embarrassed of having doubted the man, and humbled by his generosity and hard work, I tipped him again before loading the bike up and heading out into the Sahara. The cities are full of people who will harass you for money and it’s wise to be vigilant to this, but you will be bowled over by how kind the vast majority of people in this country are to travellers. Fes is a fascinating place to spend some time if you want a break from the bike, with plenty of interesting attractions and activity to fill a rest day.

It was after leaving Fes that the fun motorcycling really started. The N13 heads south from the city and is a fantastic road with long sweeping bends that take you into the peaks and give the full view of the vast desert you are passing through. I continued this road to Errachidia and onto Merzouga the following day. The latter part of this turns into long straight desert roads which can be a bit of a slog in the heat, but it is worth heading south to experience the vast sand dunes and rolling desert scenery.

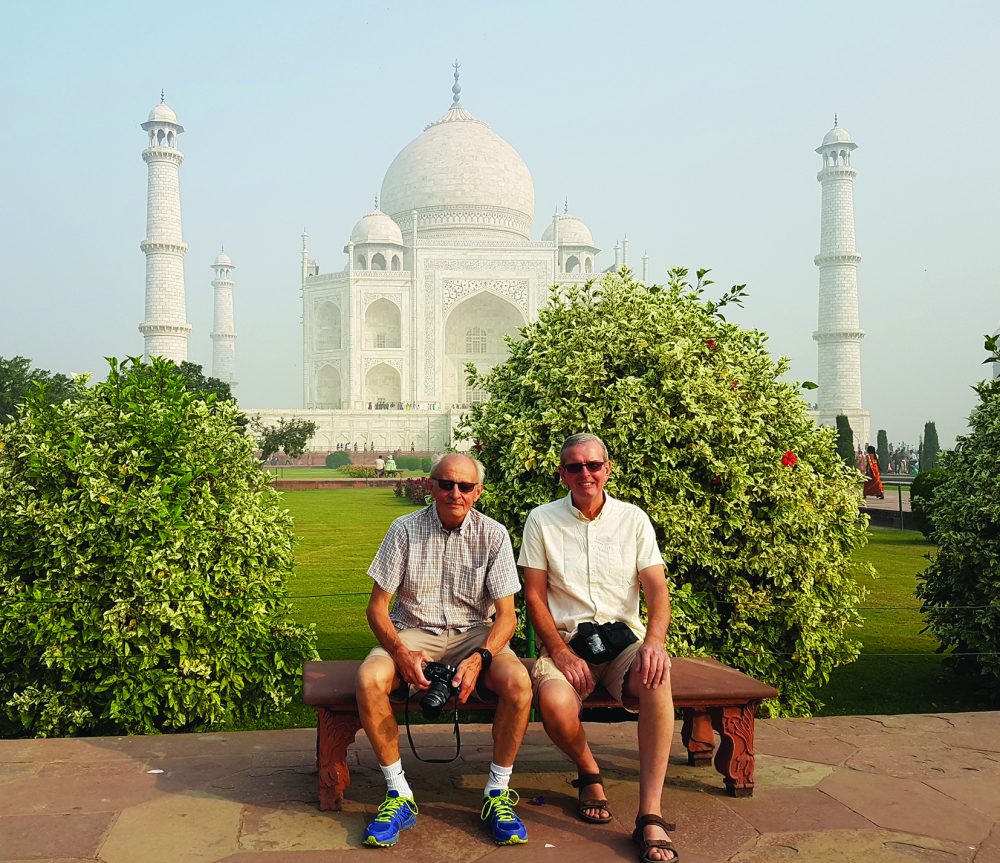

Touring in Morocco on my FZ8

Another must see whilst in this part of the country is the Todra Gorge, with its single-track mountain roads through the vast canyon of the Todra river and the famous mountain pass of Dadès Gorge. Even in peak season, these roads are reasonably quiet and are the perfect playground on two wheels. The scenery will take your breath away around every corner too.

After a couple of days of exploring mountain passes, only to eventually discover they turned to gravel tracks and turning back (on account of my lack of knobbly tyres), I picked up the famous Tichka pass, which takes you north from the Atlas mountains and into Marrakesh. I was looking forward to Tichka, but had unfortunately timed it with some fairly major resurfacing work, meaning dozens of harsh gravel sections which were causing punctures in trucks and 4x4s. Miraculously I made it through without an issue and into the city. Biking through this bustling city in the heat was not an experience I would repeat in a hurry. On approach I was harassed by kids on mopeds trying to sell me directions, something which was made worse when a local crashed into the back of my bike as I stopped to avoid a pedestrian. Fortunately, we were both okay and there was no damage.

It was in Marrakesh that I decided to wander the souk, an experience I would highly recommend. Largely unchanged in format for centuries, the souks are a labyrinth of stall traders and a fascinating insight into Moroccan culture. As I have a love of cooking, I treated myself to a traditional Moroccan tagine. Looking back, buying fragile cookware when you’re a thousand miles away from home on a motorcycle, isn’t the most sensible thing to do. And in a scene which wouldn’t have been out of place in a ‘Top Gear’ special, I found myself disposing of some of my best Primark apparel to accommodate it in the top box. I was extremely pleased, and shocked when I unpacked it in Reading with not so much as a chip on it.

The day had arrived for me to head for the port and back to Europe. I had seen the best bits and always planned for a day of motorways, it seemed a fair trade off for more time in the Atlas Mountains and rest days exploring the cities. The port at the weekend is far busier and chaotic than during the week, with ferry timetables seeming to go out the window and boats missing their arrival time slots the journey back to Spain took just shy of 12 hours, and I arrived in the early hours of a Monday morning. I had enough time during the final leg of the tour to ride round the Algarve before heading North through Portugal, crossing Northern Spain, into the Picos and back to Santander for the sail home. I arrived back home late Sunday night before dragging the bike back out for the Monday morning commute up the M4 into London, still covered in red Saharan dust.

Fantastic roads, unbelievable scenery, a warm and welcoming culture and great value for money means I’d highly recommend Morocco as a biking destination. One of the best things about motorcycle travel for me is the feeling of how joined up the world really is, and this is hard to ignore after a trip to this amazing country. You can leave your home in the UK, jump on your bike and a few days later be riding past some sand dunes in the Sahara Desert. There are a few ferries and a bit of paperwork to navigate in between but it really is that simple. You do not need any expensive equipment or special vehicle to visit Morocco – I am a firm believer that the best Adventure motorcycle is the one stood in your garage – just a bit of common sense and a thirst for adventure.

A few tips for first time visitors:

Motor Insurance and Currency

The Moroccan Dirham is a closed currency, meaning it cannot be bought outside of Morocco. Entering Tangier, you will see kiosks selling the Dirham which is roughly 12 to the Pound.

On arrival the port authority will ask for your V5 and they will issue you with a small card. Use this at a kiosk in the port to buy your Motor Insurance, which cost 30 Euros for 10 days. Periodic police checkpoints in Morocco will ask you for this card so keep it somewhere handy. Most checkpoints wave you through and if they do stop, they are very friendly with no issues.

Accommodation

Accommodation is inexpensive in Morocco. Even in the relatively touristy rural areas of High Atlas and Dadès Gorge, you can get a nice room with breakfast and dinner included for around 25 euros. I was in Morocco in late September and early October, one of the most popular times with travellers avoiding the height of the summer and never struggled with finding somewhere. I tended to book a day ahead online but had a couple of times where I just found somewhere en-route.

It’s worth checking out the Riads. These tend to be family run and have 2-3 rooms. The hosts I met were incredibly accommodating, and they were great value for money. A great way to get a more local feel and some delicious home cooking.

Food and Drink

You will find plenty of roadside restaurants, and supermarkets are common in the towns for lunch on the go. For those worried about food hygiene, most traditional Moroccan dishes are slow cooked so I had no real issues. Avoid salads and drink bottled water only. Hotels and restaurants do not serve alcohol, but it’s easily found in supermarkets if you want a few cans.

Local driving

As you can probably imagine, the driving standards are not quite on par with, say, TVAM standards. There are broadly two types of vehicle to watch out for, the 40-year-old Mercedes van with four odd wheels carrying 8 tons of luggage on the roof, and the highly impatient tourist minibuses. Neither want to wait for you, or get out of the way, and neither will factor their vehicle’s limitations into their overtakes. Go round every corner expecting the worse and be ready to back off. If you brave the motorway for whatever reason, be extra careful.

The road quality is also worth mentioning. The surface is generally good, however I encountered lots of road improvement works which see you sent out onto a gravel track for a short stretch. I was on road BT023 Battlax sport touring tyres on the Fazer and was fine but keep this in mind, both when riding and deciding whether to pack for puncture repairs. If you are on a bike with off-road capability this should be no problem at all.

Safety

As a precaution I kept my camera in my lockable top box and all my documents, money and phone in my tank bag which I never left behind…exactly the same as I would at home. I took a lightweight lock and used it but rarely felt like it was necessary.

In terms of personal safety, I never felt at risk in the rural areas. Wandering around the cities alone at night is not advisable, particularly in Fes. If you want to go out to a restaurant, your hotel will arrange someone to take you and bring you back.

First published in Slipstream November 2020

Resources

Morocco Overland by Chris Scott is a great book to have whilst planning your trip. Geared up to those going off the tarmac but also extremely useful if you just plan to stay on it!