As we reach the end of the decade and another season packed with motorcycle shows has wrapped up it’s worth reflecting once more on where the last ten years have brought us, and where we might be going. The age of the superbike is over, and the age of the hyperbike has begun. But so, I would argue, has the age of reason.

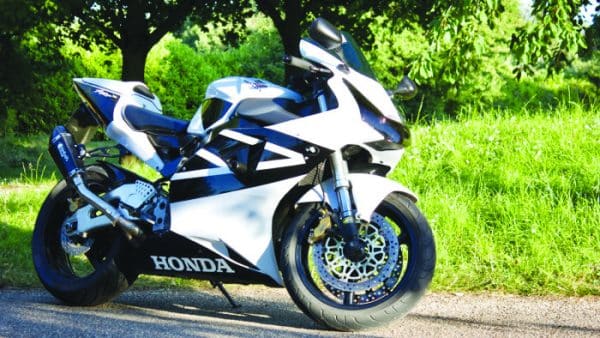

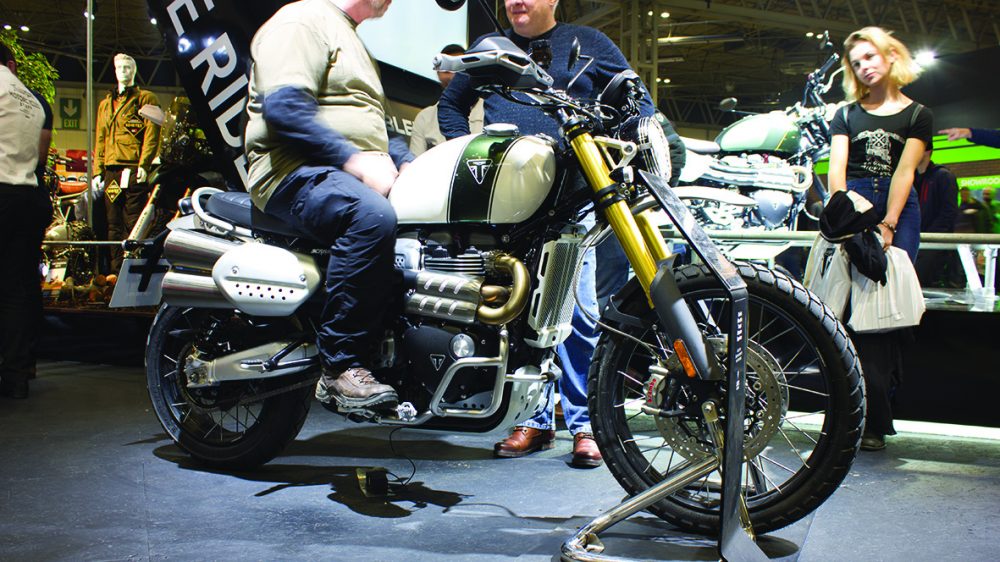

With the launch of the new Honda CBR-1000RR-R Fireblade, the last of the sensible road-biased 1000cc sportsbikes is dead, and a new era of £20k+ exotica is upon us. At a time when fewer and fewer new riders are choosing to embark upon their motorcycle journey, the crossing of this psychologically important barrier is triggering a wave of introspection across huge swathes of the biking community.

Such flagship models are now well and truly out of reach for the vast majority of riders. And even if you are personally financially capable of placing such a vehicle in your garage for the length of a PCP contract, the value proposition becomes ever-harder to justify when the real-world application of these bikes has shrunk at a rate inversely proportional to their rapidly rising cost.

A laser-focus on on-track performance has destroyed any real-world usability litre-class sportsbikes once possessed. Big adventure tourers like BMW’s R1250GS, KTM’s 1290 Super Adventure and Ducati’s Multistrada 1260 Enduro have gotten bigger and heavier to the point that they’re now no longer effective as all-road devices, more akin to two-wheeled Porsche Cayennes than Land Rover Defenders. The sports-tourer genre used to be where softer, slower sportsbikes lurked in order to avoid unflattering comparisons with razor’s edge performance machinery of the day. Yet Kawasaki’s H2 SX uses a supercharged 1000cc engine to warp space and time in a way that speed freaks from the golden age of sportsbikes could only dream of.

Don’t get me wrong – I love that these machines exist. But they exist now purely as statements, both of the technical capabilities of their manufacturers and the girth of their owner’s wallets. They have fully embraced their role as the Lamborghinis and Ferraris of the motorcycle world: expensive toys designed to mollify the wealthy rider’s ego with the knowledge that, if called upon, they could comfortably outrun a category five tropical storm.

Small Ones are Juicier

Not too long ago, mid-capacity motorcycles were considered to be temporary stepping-stones with zero street cred and significantly reduced build quality and specification. To roll up at a bike meet with “only a 600” was to invite ridicule and mockery. This attitude persisted for decades, with PCP providing a way for the illusion of affordability to persist in the face of soaring price tags. But now that thread has finally snapped, and there’s a kind of freedom in finally accepting that the vast majority of us can safely ignore the top-shelf selections entirely.

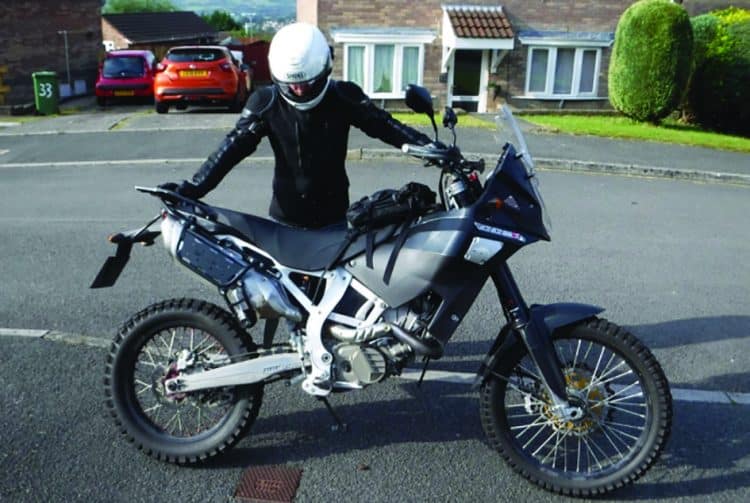

One of the best adventure-tourers on the market, featuring “only” 850cc of displacement.

What’s more, today’s mid-capacity bikes are a far cry from the bargain-basement parts-bin specials we remember from twenty years ago. The variety, capability and equipment level you can now purchase for half the price of the top-range machinery is truly remarkable, often far in excess of top-flight machines from just a few years ago.

890cc only seems small because KTM has desensitised us with their 1290cc version.

That Ducati 916 you always promised yourself one day? A new Panigale V2 will outrun it on the straights and leave it for dead in the corners, all while using less fuel and with service intervals that would’ve seemed pure fantasy just a decade ago. You really don’t need a Panigale V4, and now that you can’t afford one, you can happily forget all about it.

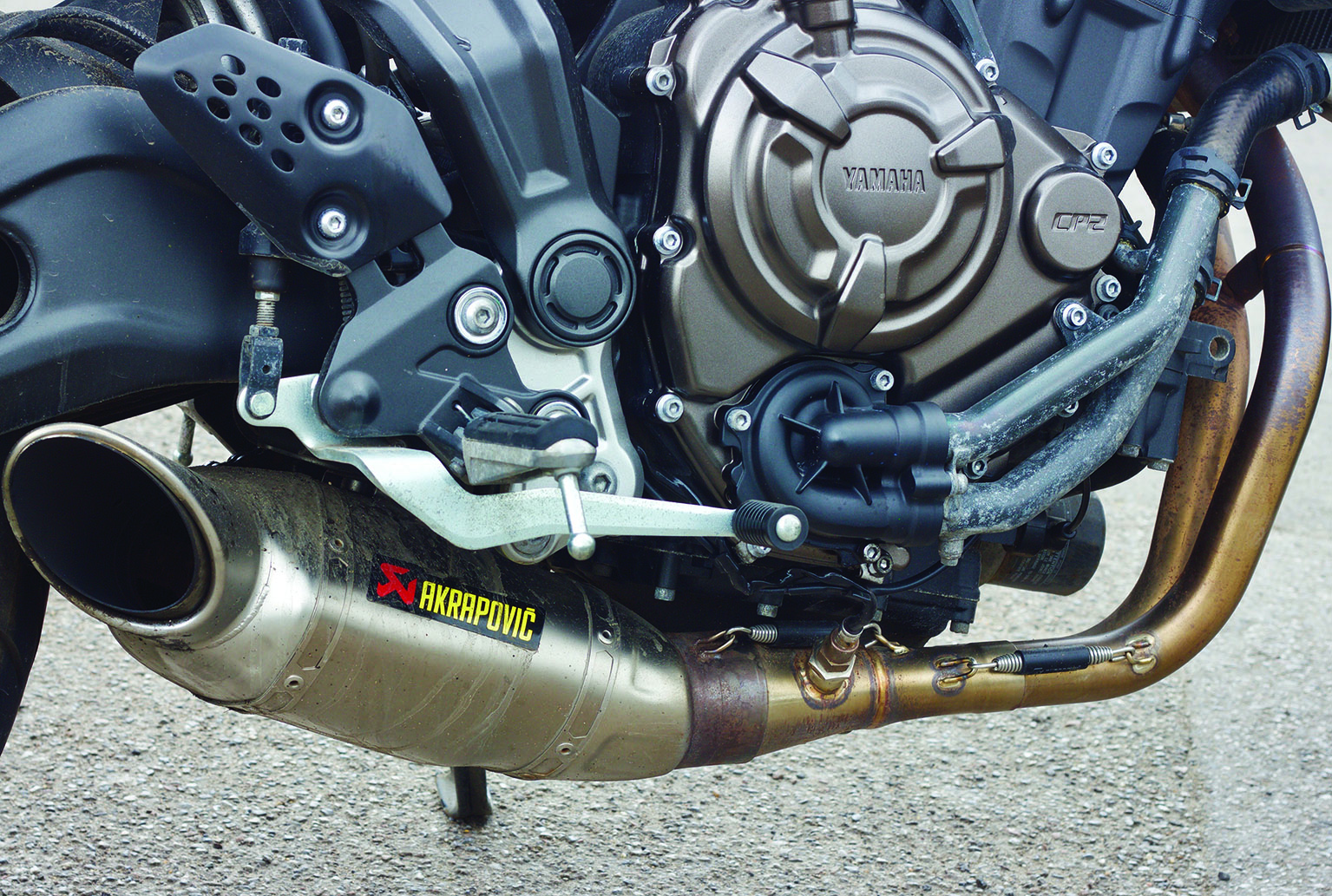

Owners love their Yamaha FJR1300s, and in ages past the brand’s Tracer 900 would’ve been ignored as a low-powered learner-tolerant alternative. But the FJR is heavy, thirsty, and not noticeably more powerful than it’s significantly cheaper stablemate. You’re not giving up build quality or electronic toys, nor are you noticeably sacrificing luggage capacity or pillion comfort. You get high-spec brakes and suspension, just like you’d expect on a flagship high-performance machine, and all for less than £10,000. The fact that Yamaha sells every one they can build supports my thesis that the era of egotism and excess is indeed over for most riders. Perhaps now we can finally agree that 115bhp is more than enough for a road bike and that choosing a “smaller” machine is no longer a sign of mental, physical, or sexual deficiency.

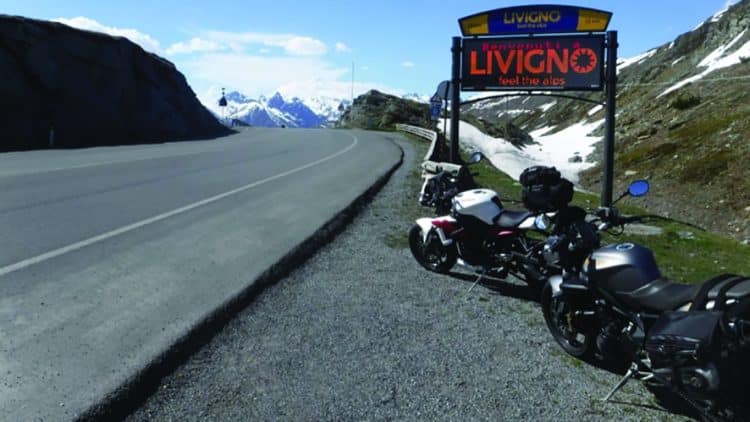

I’ve ridden and loved the Tracer 700 and the updated version looks fantastic. What’s more, the Euro5 updates don’t seem to have dented the power output nor added to the weight – it’s fully-fueled and ready to propel you across the continent at a lithe 196kg, and all for just £7,400. But nothing better highlights the “less is more” era we currently find ourselves in than the new Yamaha Ténéré 700. Sharing the same drivetrain as the Tracer and MT07, the Ténéré asks buyers to dig a little deeper at £8,700, but in return delivers far more capable off-road performance than any of the big-capacity flagships. KTM’s 790 Adventure pulls off the same trick, proving once and for all that anyone who tells you they need the bigger 1290’s power output to scramble down green lanes is lying to themselves, as well as to their bank manager.

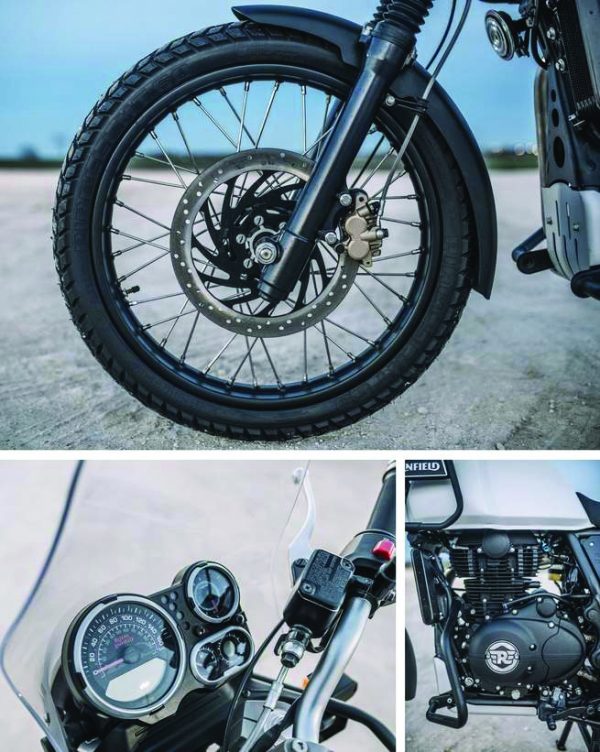

Want to cruise in comfort? 650cc is plenty, and a £6,600 price tag is welcome.

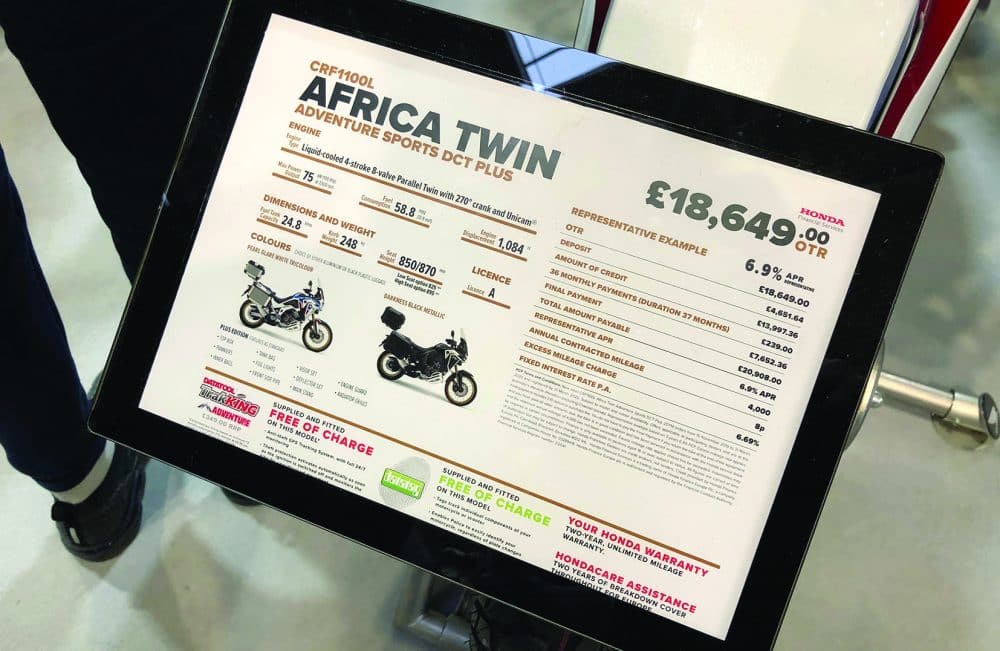

BMW’s new F900XR makes the far-more-expensive, thirsty, and heavy S1000XR largely redundant for most riders. Anyone contemplating the purchase of a new Honda CRF1100 Africa Twin for an off-road adventure hasn’t seen the price tags, nor spent much time in the dirt and mud, where the brand’s own CRF250L reigns supreme. At almost £20,000, a top-spec Africa Twin will now cost you more than four CRF250Ls. You could pay for three friends to join you and still save money.

I’ve ridden and loved the Tracer 700 and the updated version looks fantastic. What’s more, the Euro5 updates don’t seem to have dented the power output nor added to the weight – it’s fully-fueled and ready to propel you across the continent at a lithe 196kg, and all for just £7,400. But nothing better highlights the “less is more” era we currently find ourselves in than the new Yamaha Ténéré 700. Sharing the same drivetrain as the Tracer and MT07, the Ténéré asks buyers to dig a little deeper at £8,700, but in return delivers far more capable off-road performance than any of the big-capacity flagships. KTM’s 790 Adventure pulls off the same trick, proving once and for all that anyone who tells you they need the bigger 1290’s power output to scramble down green lanes is lying to themselves, as well as to their bank manager.

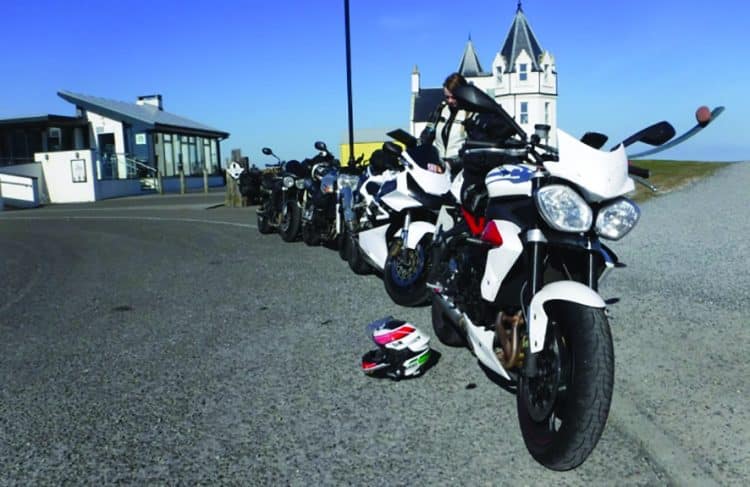

Want something sportier? 700cc is all you need to tour Europe.

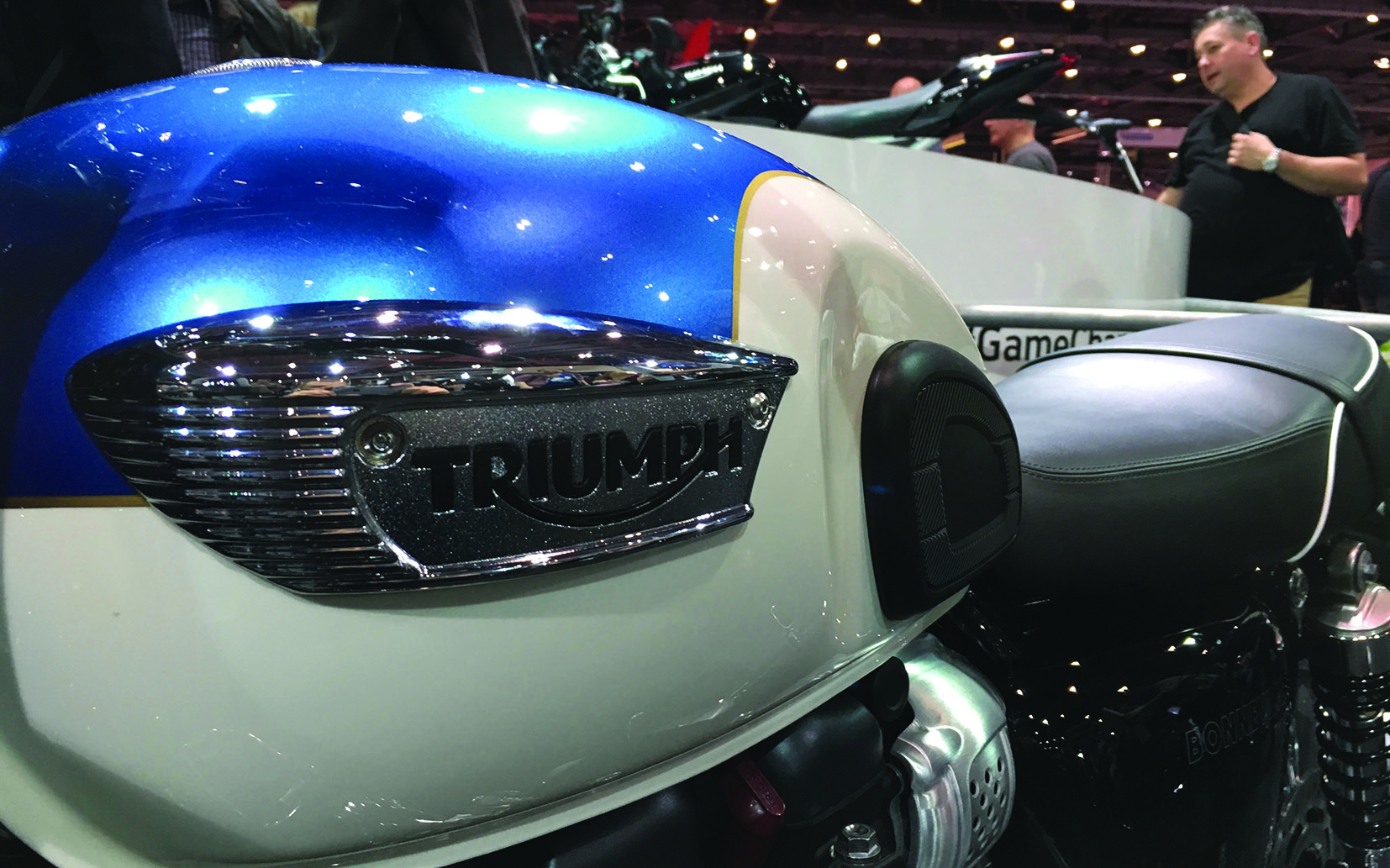

Buy this bike on PCP and it’ll cost you almost £21k. Not interested.

BMW’s new F900XR makes the far-more-expensive, thirsty, and heavy S1000XR largely redundant for most riders. Anyone contemplating the purchase of a new Honda CRF1100 Africa Twin for an off-road adventure hasn’t seen the price tags, nor spent much time in the dirt and mud, where the brand’s own CRF250L reigns supreme. At almost £20,000, a top-spec Africa Twin will now cost you more than four CRF250Ls. You could pay for three friends to join you and still save money.

Harley-Davidson’s idea of downsizing is entertaining, with their physically-imposing and aesthetically-challenging Pan America displacing a claimed 1250cc, matching all but the very biggest of its European competitors’ flagships in the segment. Even the 950cc Bronx is hardly a small machine, while unlikely to register as a serious alternative to Triumph’s existing Speed Triple or its ilk. Price, as well as weight and power figures, will be very telling. But as the new Indian FTR1200 has lately proven, American cruiser manufacturers are facing an uphill battle to compete in these market segments.

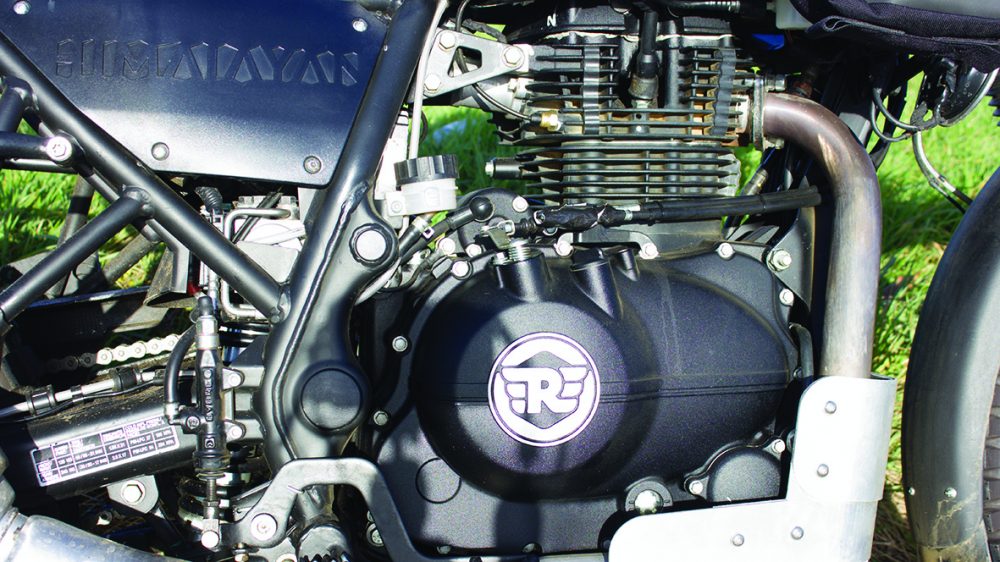

As a rider interested in exploring some off-road adventures after even a 650cc Suzuki V-Strom proved too large and cumbersome for the Trans-European Trail, I am delighted to see Fantic making some serious moves in UK market. Their interesting new Caballero 500cc single-cylinder road bikes appeared in magazine reviews earlier this year, providing a cheaper (and purchasable) alternative to CCM’s many hand-made Spitfire variants. What’s more, they offer a selection of 50cc, 125cc and even a 250cc road-legal enduro bikes, undercutting Honda’s popular CRF250L on both price and weight. Colour me interested.

Continuing the off-road theme, Husqvarna has diverged from their KTM overlord’s 690 Enduro by adding a Long-Range (LR) variant to their 701 Enduro. With 25 litres of fuel, the frugal and well-equipped single-cylinder motorcycle should be good for more than 300 miles of off-road riding. Only the BMW R1250GS Adventure claims a similar tank range, yet costs almost twice as much and would get itself wedged solid on trails a Husqvarna rider would breeze along. For those seriously planning some long-distance off-road adventures, the showroom choices have improved markedly this year.

How fast do you ride off-road? 250cc versions are available too.

The second evolution of the motorcycle?

Which brings us neatly back to the very start of this piece. For years, bikers have persuaded themselves and each other that they needed more power, more engine, more speed, and manufacturers were only too happy to oblige. We pushed them harder and harder, to the point where whole new kinds of electronic rider aids had to be developed to keep these new monsters in check, and still we demanded more. But now the bubble has burst, and we’ve finally realised that not only can smaller, cheaper motorcycles be just as fun and capable as their high-end cousins, in many cases they can actually be better in almost every way.

The Cycle Begins Anew

And not a moment too soon. Because while the motorcycle industry continues to wrestle with chronic addiction to baby-boomer cash, competition is arriving from an unexpected and ironic source. Motorcycles were originally born from bicycle manufacturers bolting early petrol engines into beefed-up frames. And while our evolutionary offshoot has produced the dinosaurs of our time, the meteorite of demographic, social, and political change is poised to kill it off entirely.

Threat or salvation? Motorcycle alternative or stepping-stone?

In the meantime, the original strain has persisted, and in the last ten years has begun to rapidly mutate. Across Europe, more bicycles are now sold with electric motors than without. These electrically-assisted bicycles take the bite out of hills, provide a safeguard against exhaustion, and are even providing a way for older or less fit individuals to get some much-needed exercise. As legislation begins to choke the life from the motorcycle industry in its current form, this unlikely competitor has emerged to nibble at the edges.

Boutique builders may one day be all that remains of mainstream motorcycling…

Prices have plummeted, and a high-quality multi-purpose e-bike with luggage rack, lights and mudguards can now be had for under £3,000. In increasingly-densely-populated urban centres, even a motorcycle no longer makes sense. And while a traditional bicycle might leave you arriving at work hot and sweaty, an e-bike does not. All these factors combined mean that motorcycling is fighting for relevance in a world increasingly hostile to its very existence.

It’s entirely possible that motorcycling can co-exist with autonomous cars and swarms of cyclists, both in terms of space on our roads and room in our budgets. But if it does, it will be as a much smaller version of itself, and with much smaller, more affordable motorcycles. There will always be room for high-priced exotica, and people willing and able to purchase and perhaps even ride them. But those few riders alone won’t keep the bike cafés open, the leather and textile makers in business, nor provide enough of a voting population to keep the encroaching safety legislators at bay.

Manufacturers follow the money, and if we show them that mid-capacity motorcycles can sell, then more will come. This will make the sport more affordable, and if we desist in our hostility towards small-capacity motorcycles and their riders, then perhaps some of those e-cyclists will be tempted to try something faster, without pedals. The next ten years will make or break motorcycling in the UK, and perhaps the whole of the developed world. E-Bikes could save us or destroy us, and the outcome is entirely up to whether we can embrace a small-capacity future or choose to hide in the past.

Nick Tasker

First published in Slipstream January 2020