All the Ukrainian names have been changed. I deliberated about keeping original names. The Ukrainians I met deserve to be recognised – but then I imagined a Russian hit squad driving around with this book, shooting everyone I’d mentioned in it. The truth is, almost everyone mentioned here is already visible on Social Media but – I decided not to take the risk. And so I changed all the names.

Part 1: Arriving in Ukraine in a van

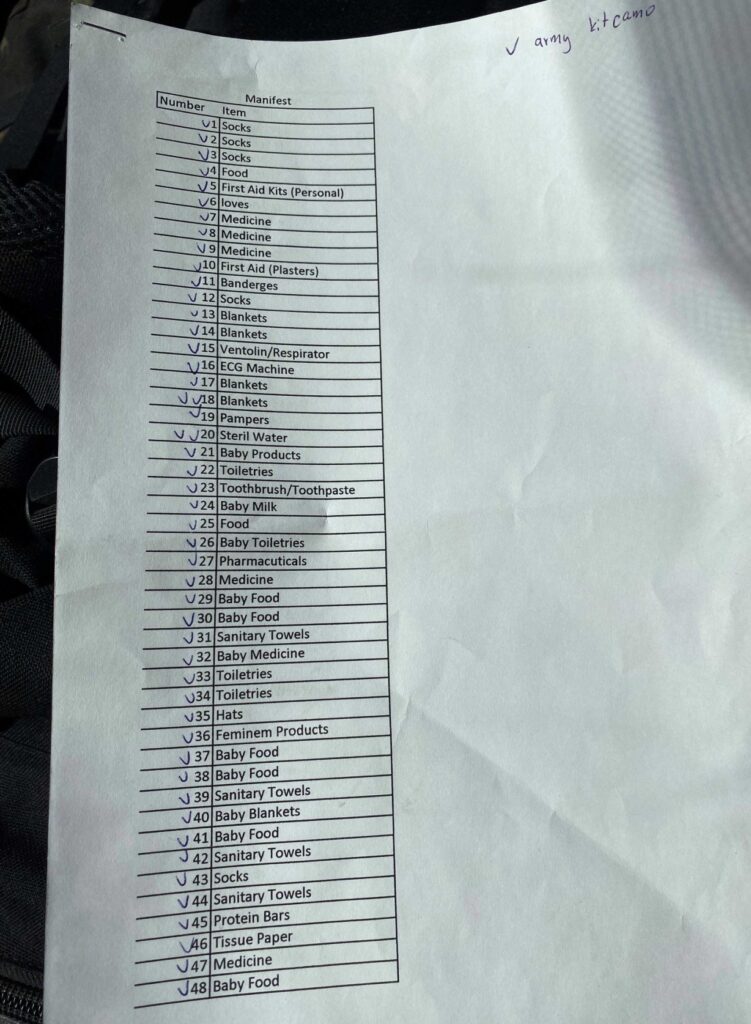

My name is Titus and recently I made 7 trips across the Ukrainian border carrying aid. The first two trips were with a mate, Karl, in his van. We didn’t know it at the time but, along with toiletries and rucksacks and medicines, we carried pre-programmed laptops for Special Forces based around Kyiv – and, of course, a myriad of things specific to women and children. I should mention that before we set off, I went on Facebook and asked if any of my Facebook chums fancied chipping-in for the petrol. I thought it would be cool if I got, say, a hundred quid… but, over the next couple of months or so they gave me £10,000. Initially, we drove from Reading (10/03/22) to the Ukrainian border in a fairly direct route. My Facebook money paid for the ferry and a couple of cheap hotels but what I remember most about this trip was as we came closer to the Ukrainian border all the ‘normal’ traffic had disappeared…

The number-plates of the vehicles around us started to tell a powerful story. Spanish, Polish, Swiss and German (etc, etc), vans (some with red crosses on their bodywork) full of boxes. Almost the Spirit of Dunkirk. Europeans heading out into the unknown to try and help. I still get a lump in my throat remembering it all.

But arrival at the (Krakovets) border (12/03/22) brought us back to reality with a thump. There was a fair queue on the Polish side which actually didn’t take as long as it looked like it might…

As we progressed, there were queues of people, quite orderly but – a lot of people – a lot of refugees. I didn’t think being caught taking photographs was probably a very good idea so I snapped a couple of surreptitious ones – but they don’t really capture the atmosphere. Both Karl and I were quite shocked. I can’t think of words to explain our emotions better. There were endless coaches queued up – full of people.

… but, in contrast, the Ukrainian side was a cacophony of border guards who seemed not to know what was going on – nor how to deal with it all (all the non-Ukrainian speakers, foreign vehicles, cargos packed beyond any reasonable efforts to examine them – and a building impatience). It all starts, the Ukrainian side, with us being issued with a little square of paper, then you dump your vehicle and fight through the throng to try and get seen by Passport Control – and then customs. Passport Control is fairly simple but the customs ladies didn’t seem to understand anything and kept directing us to other customs points in alternative lanes – identical customs points!

Then we met some young Germans (with a van full of bandages) who had already been misdirected back and forth around the border area for, unbelievably, some nine hours – but immediately after Karl and I had joined forces with these young Germans we were directed from one customs point to the one opposite – who directed us straight back to the first – and I promptly lost my temper – and I started shouting at the poor young customs girl. This could have gone one of two ways but a man suddenly appeared from the gloom of the back of the customs hut and in acceptable English explained that we had a form to fill in – and he even gave us the form! And then, quite quickly, we (and the Germans) were processed, our little squares of paper were correctly stamped – and we were out the other side. Back in the UK we’d been told that border personnel were expecting us – and a corridor had been generated to allow us straight through – ha ha. So what we’d faced was very different to what we’d been led to believe!

It then transpired that our Ukrainian contact details were completely irrelevant, our main contact (Olek) wasn’t in Lviv (as we’d been told) but some 120 miles south-east in Ivano-Frankivsk. However, we phoned him and he gave us a number in Lviv – so we now drove the 40 miles west. I think, as we set off, Karl and I sort of looked at each other. We were, for us, truly entering the unknown.

There’d been talk of Russian ‘hit squads’ crossing the western border and targeting aid carriers. We were now officially in a war zone, it was dark and I think we were both expecting Russian missiles to start crashing in around us at any moment! Was that car in front of us Ukrainian or Russian? But Karl is a big, strong lad and I’m stupid enough – if anything scary turned up – we’d have fought to the death! But it was all fine and, in short time, our new contact in Lviv, a chap called Vladislav, came out and found us at a junction – and we followed him home. Turned out Vladislav, also a member of the military reserve, had quite an aid organisation he’d set up and was part of an unusual group. The lady, Anastasia, in Reading, who had organised our original cargo was a scientist and we now learned that not only was Vladislav a world leading expert in LASERs but our contact in Ivano-Frankivsk was head of the physics department at the local university there!

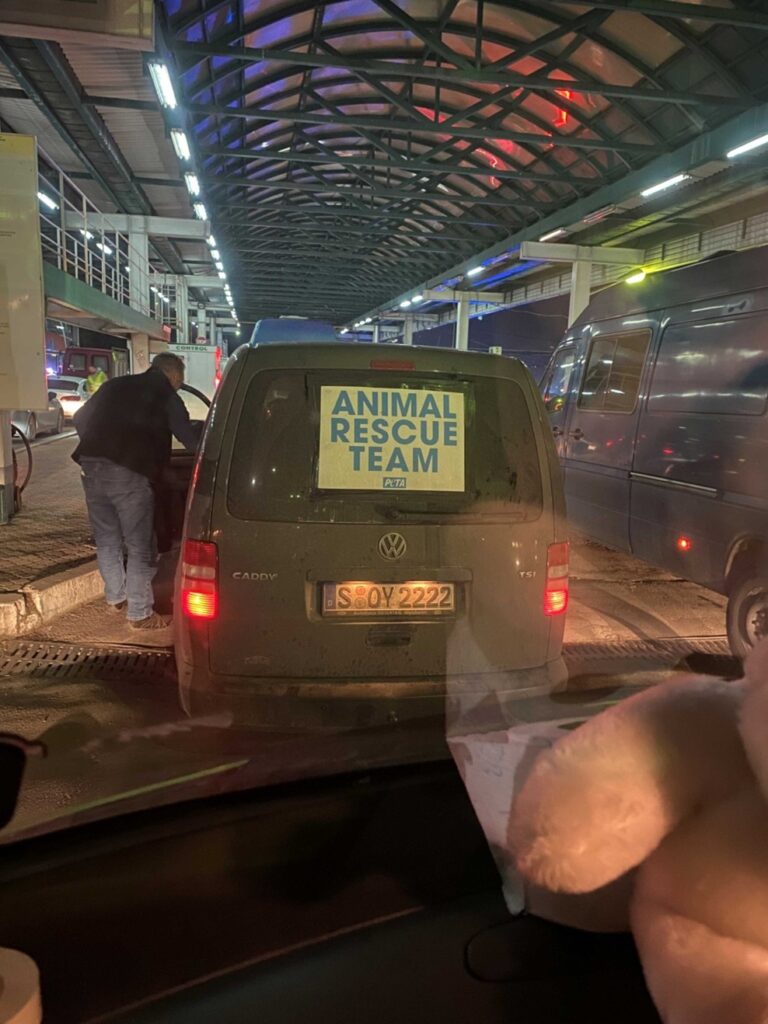

Karl and I were given sofas to sleep on and Karl (who by day is a skilled builder) made me laugh when he pointed out that the one he’d chosen was under a beam which, if we got missiled, would probably be the last thing to collapse! Then, in the morning, after unloading our van, Vladislav asked if we could liaise with an Anglo-Dutch team who had a cargo for him but were having problems crossing the border. So, after half a day of hanging around an Okko petrol station – and general inaccurate information, we found ourselves crossing into Poland in the dark via Shehyni – and behind a German VW Caddy with an ‘Animal Rescue Unit’ sign in their rear window.

So Karl wandered over with €100 for them and came back saying the van was just stuffed with animal travel-cages full of dogs and cats. Clearing the border (which was operating more smoothly than the Krakovets one), we met up with a member of the Anglo-Dutch team and were taken a half hour drive to a large farm building (with a small Ursus tractor and other such stuff in it – and, nearer the big double doors, a mountain of aid items) where we loaded their cargo of toiletries and food and sugar and baby milk (and all sorts) into our van – but then we had to spend the night in Poland – and all the hotels near the border were full of refugees – thus we were taken about a sixty miles west (to Łańcut) to find lodgings. As for the Anglo-Dutch team not being able to cross the border; the deal is that crossing is quite simple (once you know about that form which must be filled in) – provided you have your vehicle papers and passport (and the owner of the vehicle is present). Strangely, a lot of people forgot their vehicle papers and the Anglo-Dutch team had hire vehicles – so the only proof they had that they might have any rights to the vehicles they were in – were Visa receipts! And, indeed, that night in Poland I met another team, British, who had come over in a convoy of about four big pick-up trucks full of relevant stuff – but no one had thought to bring the V5s – and so they had also been turned back. As time passed, I learned that Vladislav was quite an important guy and shortly after our first arrival he had been part of a team lobbying the border authorities to make it easier for aid carriers to get through and, on about my third or fourth entry, not only was that form discontinued but the whole entry procedure became much more relaxed.

I was chatting to one of the Anglo-Dutch team and he said he was staying in a Polish refugee camp somewhere – and he said to me, “We have people there who have no idea where they are going to go. And I mean NO idea…”

The day after this (14/03/22), Karl and I took a cargo down through stunning countryside to Ivano-Frankivsk where we met Olek and his beautiful family – and his students unloaded our van. Olek’s wife made us some lovely food and their two young daughters were a joy. But they (wife and children) are planning to flee to Portugal, obviously leaving poor Olek behind. “What’s the education like in Portugal?” Olek’s wife asked me and I was forced to admit that I knew absolutely nothing about the Portuguese educational system! But it made me laugh; an academic fleeing war, unwillingly abandoning her husband, maybe about to lose everything – but all she is worried about is the education of their children. Of course she is worried about more than that and ‘made me laugh’ is a figure of speech.

And then, when we got back to Lviv, Karl said he had to go home. I thought about this for a while – and then I said I’d stay. More money was coming in from my Facebook chums and I reckoned I could use it more wisely if I remained on scene. But I stood there with mixed emotions as I watched Karl drive away.

I assisted with local movements of aid around Lviv (as a sort of driver’s mate) but (18/03/22) a few days after Karl had gone, I was lying on my bed (ex-Karl’s sofa – under the beam!) looking at my watch, it was approx 0600, when there were three enormous explosions as (apparently) four cruise missiles hit a Mig repair plant at the airport, 1.13 miles from us. We were all quite shaken after this incident and from then on we started going down into the cellar during the numerous air raid warnings (we could hear the air-raid sirens but we also had apps on our phones). Here it is translated by my Google translation app…

As the explosions tore through the air I leapt from my bed and looked to the three other people in the house. Natasha emerged from her room in a stunning disarray of underwear and copper coloured hair while Vladislav woke up and said, “What was that?” like maybe someone had dropped something unimportant in the kitchen – while Estas went to headless chicken stations. There is a large table near the entrance which looks like, for the last hundred years, every time anyone has walked past this table – they’ve dumped something on it. And now Estas was hurling junk from the tabletop around the house like a madman. Turns out, there was a fire extinguisher under the table that he was after! The silence and, if you like, the immediate return to normality after such an experience is almost unnerving. Estas stood there with his fire extinguisher, Natasha and Vladislav still trying to catch up with what exactly had happened (Vladislav was probably thinking about LASERs). Initially, I just stood there wondering if another missile would suddenly plough into our house, vaporising us all – and then I went and put the kettle on. And then it dawned on me, we ought to go and have a look outside! Outside, everything was normal except over to our right was an incongruous plume of piebald smoke slowly rising above the thin strip of sunrise orange.

At the request of the group in Lviv, I bought them a €2,000 van (which Vladislav arranged Polish professors in Poland to purchase). Actually, he threw one arm in the air and shouted gloriously, “I shall get the Polish professors to buy it!” and when I said, “For goodness sake don’t allow an academic to buy a vehicle…” he simply laughed at me. Later the same day as the cruise-missile strike, 18/03/22, I travelled out of Ukraine, back through Krakovets…

Karl and I had witnessed some pretty upsetting sights at this border and my trip on foot wasn’t any better. You see groups of women and children (frequently with dogs) approaching the border dragging those granny type shopping trolleys… it is often obvious how the adults are working to keep the children’s spirits up. Sometimes cars pull up near the border; everyone gets out, there are hugs and then the man gets back into his car and drives away. Males between the age of 18 and 60 aren’t allowed to leave Ukraine.

Then I had to catch a refugee bus, which was quite an experience. You see, I’d been given a complex set of instructions as to which bus I was to catch and, I can safely say, I hadn’t understood a single word of it. Initially, it had been said that a Polish professor would pick me up at the border but, it makes sense, the border, with thousands of refugees flowing through it, isn’t really geared up for people dropping and collecting other people, willy-nilly. So, I had been told to walk through the Ukrainian side, into Poland – and catch a bus. Sounds simple but somewhere in the Polish to Ukrainian to English translation it had got some knots in it! Waving goodbye to Vladislav at the border, I set off – working on the theory that something would probably ping out of the ether and help me! I hadn’t bothered telling Vladislav that I had no idea what he was talking about because I was pretty certain any further explanations would make it all worse. The Ukrainian side was okay; I queued with everyone else, some people were clearly upset, some were laughing. Some had small dogs sticking out of rucksacks, children looked at each other (sometimes making friends), a lady ambled through this slowl-moving crowd giving out chocolates – and there were free drinks and simple food. I tried to give the food lady €20 but she seemed quite snotty and refused it. I didn’t really understand this but I tried the same thing on the Polish side and she refused the money too, but she was quite friendly and simply said they weren’t allowed to accept donations.

Having cleared the Ukrainian side one enters Poland and groups of firemen were there to help those that needed help. They carried luggage and talked to the children and did all those things that bring a lump to your throat. And then we all filed into a huge red tent which would protect as many people as possible if it rained. But I remembered this section from when Karl and I first came through. It had been absolutely packed with refugees and we’d been quite shocked. Funny to think that I was now a part of it. Still, all for a good cause. The Polish side is straight-forward so, in short time, I now needed to work out what an earth they’d been talking about re the bus… But, fortunately, and quite quickly, I spotted a Polish military officer. “Do you speak English?” I asked him, hopefully. And he did – so I phoned my Polish professor contact and, Hurrah!, the Polish officer understood exactly what I was supposed to do – and, literally one minute later, I was on the correct bus. The Polish officer understood that I wasn’t the brightest star in the firmament so he simply said, “Sit there until the bus stops again – and then get off…” I thanked him profusely and did exactly that.

This bus wasn’t too bad (by this I mean than on a future occasion, when I was again on this bus, there were some heart-rendering emotional breakdowns which I will never forget – for the rest of my life) and it dropped me about four miles west of the border at a tremendous refugee reception centre (which might have previously been the ‘trade and storage centre’ called Hala Kijowska in Mlyny).

However, I didn’t get to see this refugee centre this visit because, waiting for me as I stepped down, was a man whose name I thought I had embarrassingly forgotten (but now I’m sure it is Wojciech S – and he is a lecturer of electrochemistry!) – and we immediately drove a hundred and fifty miles to an industrial area of Kraków where my new van awaited. En route we chatted. Turned out his wife had cats and he had a Moto Guzzi! Then he stuffed me in my 2002 Peugeot Boxer 2.8 diesel van (which I hadn’t paid for yet!). I put over €100 of Diesel in it and then, having synchronised satnavs, I drove it another sixty-five miles to the Silesian University of Technology in Gliwice. Here, while his students filled the van, I went on-line and paid for it (well, really that was my Facebook chums!).

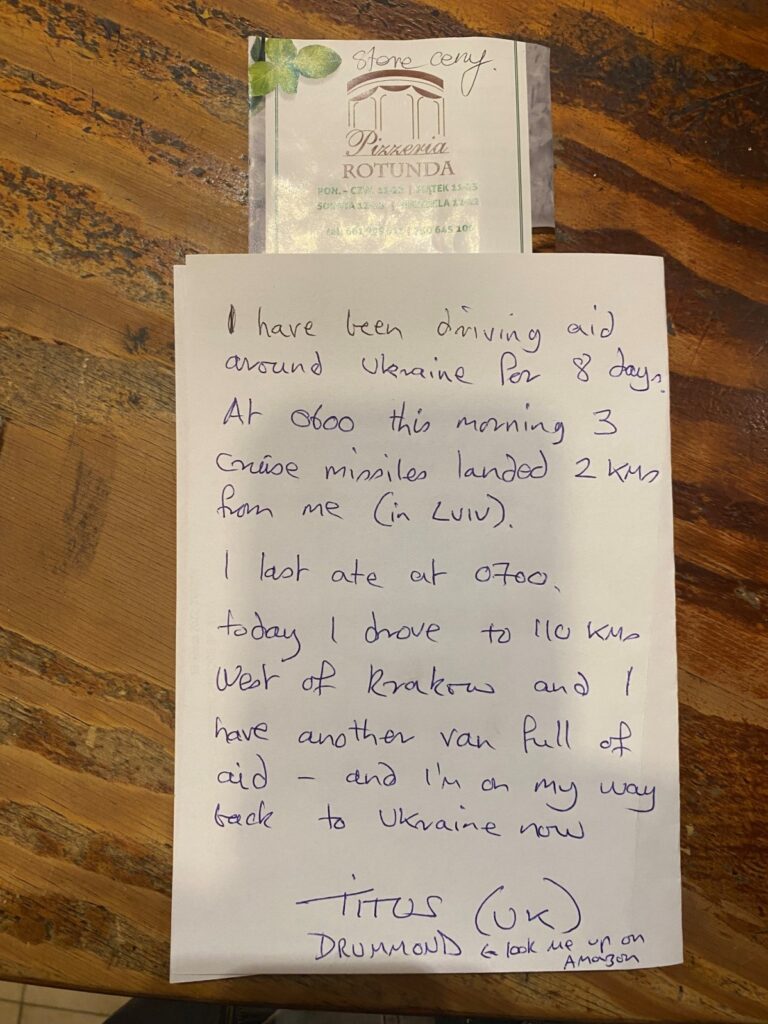

Heading back toward Lviv, the van had certainly lived and the ignition key (the only key) only operated the driver’s door and I also discovered that the fuel tank leaked if you filled it over half full. But anyway, I pulled in at Tarnów, just over a hundred miles from the border, looking for a hotel… Now I’ve had a number of rows with hotels and campsites over the last (Ukrainian) period. To start with, most of them want and arm and a leg in exchange for bed and then everything in them shuts early. So, at the place I found in Tarnów, Hotel Kardamon, which was advertising itself as a hotel/restaurant, the restaurant shut at 2100 – which was exactly when I arrived. “Can’t you make me a sandwich?” I asked hopefully (and politely) but from their response you’d think I’d attempted to have unnatural sex with their statue of the Madonna. And then they pulled the ‘can’t speak English’ trick. Now, I’ve stayed at that hotel a number of times since this first visit (and I quite like the place now) – and they speak English fine! So… returning to this first visit en route from Gliwice to Lviv, I asked where I might get something to eat – anything to eat – and they (in their not-English) recommended a pizza place in town, which said it delivered. So the girl behind the bar/reception-desk phoned the pizza place for me – and discovered they now no longer deliver. Just great, isn’t it! Anyway, the pizza place said they closed at 2200 so I jumped back into the van and, it was hard to find, but I found the place before 2130 – and in I went. And, after denying they spoke any English either, they told me they were shut. I had a slight sense of humour failure (you could probably hear the explosion back in the UK) but I showed them their time table that clearly stated 2200, I pointed out quite loudly that we’d phoned them only a few minutes earlier and then, working on the theory that if they couldn’t speak English, they might be able to read it – I wrote them the following note!

The three ladies behind the counter each, obviously unable to understand a single word, read my note. Discussed between themselves – and then they made me a pizza and, if I remember correctly, they wouldn’t take any money. Back at the hotel, I sat down in my room and opened a package the Polish scientist had given me. It contained six tins of Okocim beer and, as they say, all’s well that ends well! But, going back to my row with the hotel; aren’t these organisations supposed to help a traveller. Isn’t that what hotelling is all about – surely it’s not just about money?

Arriving back in Lviv the next afternoon (19/03/22), a member of the Koyot Special Forces, who had driven across from Kyiv to collect their laptops (and all the other gear we could stuff into his car), turned up. I’ve intermingled with Special Forces all over the place and I’ve been involved more than once but I felt, under the circumstances, meeting this particular Koyot was a special privilege. And the day after this I made a second run to Ivano-Frankivsk where I was once again fed wonderful food and I was fascinated by the apparently ancient lift in Olek’s building. I believe it originated from the Republic of Belarus but it has always (for years) spoken in Russian. However, shortly after the Russian invasion, engineers arrived and changed all its messages to Ukrainian!

For the next couple of days I helped loading and unloading vehicles. I met all sorts of people who were fearlessly making exceedingly risky runs into scary parts of Ukraine. Vladislav and I visited relevant stores trying to buy warm military-equipment but everything was of poor quality and I was quite disgusted that none of the shops would offer me any discount. Vladislav and I bought some limited kit from a sort of paintballers shop called Scout Tactical but I wasn’t very impressed with much of the kit – and they were out of most stuff anyway.

What did shock me slightly there were the couples wandering about with the girls seeming to be saying things like, “Ooh, that’s a nice knife; you should get one of those…” and looking admiringly at their boyfriends who were buying cheap Chinese compasses and torches and all sorts of stuff that was just emptying their wallets. But I suppose they were all entitled to these moments; feeling the thrill of patriotism and of love and of togetherness… So Vladislav and I went home; I bought €1,000 worth of food for the city of Mariupol – but now besieged by Russian forces it was impossible to get the food in. Then, out of the blue, the mayor of the city of Poltava phoned Vladislav saying they were desperate for food, so it was quickly dispatched to Poltava. Vladislav has no idea how the Mayor of Poltava knew to phone him, let alone got his number. I filled up everyone’s cars with fuel, bought them (the aid team) a pile of food and on the 22nd of March I got Vladislav to drop me back at Krakovets. I’d done good justice to the money from my Facebook chums but more was still trickling in – and I was developing a plan. But I had to get back to England first.

I was now an expert at getting through the borders and they’d also seemed to have relaxed a bit but my second trip on the refugee bus was considerably more distressing than the first because there was a child who just screamed and screamed. His mother was in a similar state and completely unable to do anything for the boy and she also had a second, younger, child to tend to. Everyone wanted to help but neither the child nor his mother were consolable and, bearing in mind that most of the other people on the bus were also fairly traumatised… what can I say. I wanted to hug them, tell them it was all going to be okay… but you can’t. It doesn’t work like that. I think I’m crying writing this…

Previously, I hadn’t entered the refugee reception centre but now I went in. There were countless food stalls (everything free) operated by countries from around the globe, even Japan, but, I noticed, no representation from the UK. I was offered food a number of times but, even though I was hungry, I felt it would be terrible of me to take any – so I didn’t. There was a map of Poland taped to a pillar and showing the main Polish towns and cities. Below, in a number of languages, it said, ‘Pick a town and get on a bus – when you arrive there, people will help you’. I took a photo of the poster and immediately two armed security guards leapt on me – furious. They grabbed my camera and made me delete the photo… and, to be honest, left me a bit mystified.

Numerous camp-beds, many almost randomly scattered around the place, many occupied by really exhausted people. People who, surrounded by excited children and frightened adults – surrounded by authority issuing instructions and announcing bus departures. Surrounded by people spotting friends, crying – a jabbering cacophony. These people slept through it all. I managed to identify a bus running to a nearby railway station, called Radymno, and I noted that the poor mother and children so distressed on the previous bus were also getting on this one. So I tried to stick with them. At the railway station, I carried their luggage from the main building to the platform. I confirmed train times and got water for the children. But there were quite a few other mothers and children and they were working together now – and this, I think, helped. There were also Polish firemen around the station who were carrying luggage and children – and getting train times – and generally making their brigades proud. I didn’t mention (actually I added it later!) but many of the meeters and greeters the Polish side of the border were also firemen. On the train itself, travel was free for those with Ukrainian IDs (so I had to pay!) and opposite me were a quite young Ukrainian couple. Turns out the guy had been abroad, on holiday, when the Russians invaded – and he’d had the sense not to go back. He’d come today to the refugee reception centre to meet his girlfriend but now, of course, he was reaping the benefits Europe was offering those of his nation. In a way, I feel a bit ashamed, but something of his attitude stuck in my craw…

Overall, everything I saw in Poland, re the refugees, was absolutely awe inspiring. Well done Poland.

I spent that evening in Kraków drinking beer, mostly in a brilliant pub recommended by my Belgian policeman friend, Jörg Molleman, called Pub Propaganda, which had great atmosphere and even better beer. And then just like that, I was at Heathrow – and home.

So, that’s the background. Now we reach the part you are all waiting for. Aid runs to Ukraine on a motorcycle!

Titus Drummond

First published in Slipstream November / December 2022